Terrorist attacks provide autocrats with a favorable environment in which to mobilize public support and/or implement unpopular policies. But leaders of democratic nations can also draw on this resource of temporary mobilization and use the «rally ’round the flag» effect, albeit on a limited, institutionalized scale. As far as autocrats are concerned, they can use such social upheavals to further tighten the screws on the home front. For example, a series of apartment bombings in Russia in 1999 was used as a pretext to launch the Second Russian-Chechen War, while the Beslan school siege was used to scrap gubernatorial elections under the pretext of improving security in the regions. Observers expected a similar reaction after the March terrorist attack on Moscow’s Crocus City Hall, the largest terrorist attack since the Beslan massacre tragedy.

Although the Russian authorities did their best to find «traces of Ukrainian involvement» in the attack, and despite widespread support for this version among the Russian public (according to a poll conducted by the Levada Center in April, 50% of respondents stated that «Ukrainian secret services were behind the attack»), there was no new wave of mobilization. At the same time, our analysis of the media field highlights two immediate consequences of the tragedy: the growth of anti-immigrant sentiment, which the authorities support with their policies and actions, and the reemergence of the discussion about the abolition of the moratorium on the death penalty in the public sphere. The latter issue, despite attempts to impose it from above, did not receive proper public approval and support, which indicates, among other things, that there are certain limits to the effectiveness of Russian propaganda.

The rise of xenophobia

After publicly accusing Tajik citizens of carrying out the attack on the Crocus City Hall, the Russian authorities launched a campaign against «illegal migration,» which, in the words of the now-former head of the Security Council, Nikolai Patrushev, «creates preconditions (…) for the disintegration of the country.» Police raids were carried out in places where migrants worked and lived, resulting in the expulsion of a record number of foreigners from the country. Local authorities in a dozen regions across the nation banned migrants from working as taxi drivers and in other industries, contributing to the further exodus of migrants from Russia. At the same time, despite the labor shortage, citizens of Tajikistan, Uzbekistan, and Kyrgyzstan were not allowed to enter Russia en masse, and human rights activists began to record a surge in the number of violent hate crimes.

On April 27, lawmakers from all five factions of the State submitted a bill that introduces the concept of a «regime of expulsion» of illegal migrants from Russia if these migrants are entered into a special register for violating certain requirements. For example, in order to retain the right to enter Russia, a foreigner must not «interfere in the foreign and domestic state policy of the Russian Federation, [must] not take actions aimed at inducing the adoption, amendment or repeal of laws or other normative legal acts». Technically, any protest activity or criticism of Russian policy, including that expressed in social networks, can be equated with «incitement» to change this or that law. If the bill, which has already been approved in the first reading, is adopted, the administrative procedure of «deportation», which can only be decided by a court, will be replaced by «expulsion», which can be carried out by police officers practically at their own discretion.

It is assumed that the expulsion regime will prohibit changing the place of residence or place of stay in the Russian Federation without the permission of the Ministry of Internal Affairs, traveling outside the region established for the stay, obtaining a driver’s license, acquiring property and transport, taking a loan, opening bank accounts and transferring money, getting married, etc. In addition, police officers will have the right to request information and documents, including those constituting commercial, banking, tax and other secrets protected by law, from state bodies of the Russian Federation and authorities of foreign countries, as well as to receive information from banks on the existence and numbers of bank accounts of a foreigner in the expulsion regime, on the movement of funds on such accounts. Police officers will be authorized to carry out surveillance, including through the use of technical means, of a foreign national under the expulsion regime. This legal norm also applies to individuals and legal entities that provide such foreigners with «assistance in staying on the territory of the Russian Federation». All of this expands opportunities for official abuse and makes life for migrants in Russia even more unbearable. According to the statistics cited by Irina Volk, a spokeswoman for the Russian Interior Ministry, 65,000 foreigners have already been expelled from Russia since the beginning of 2024, and entry has been banned for another 120,000 foreign citizens.

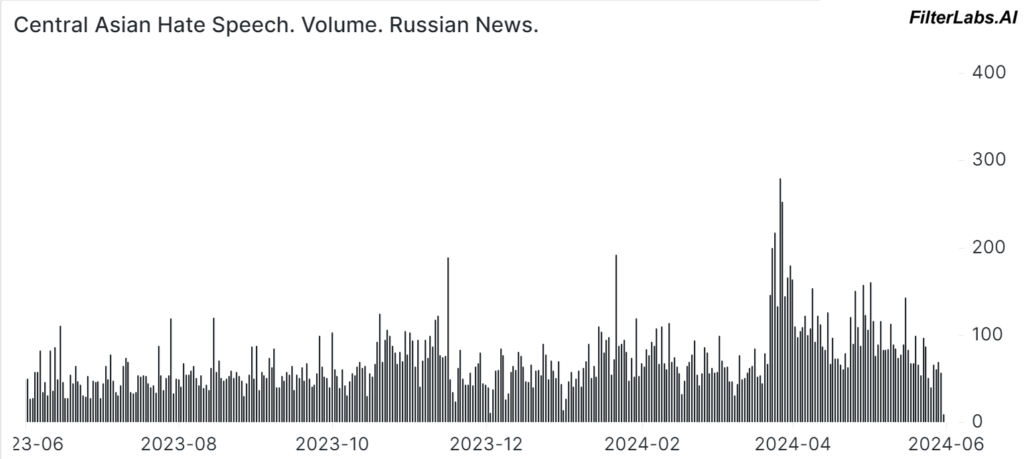

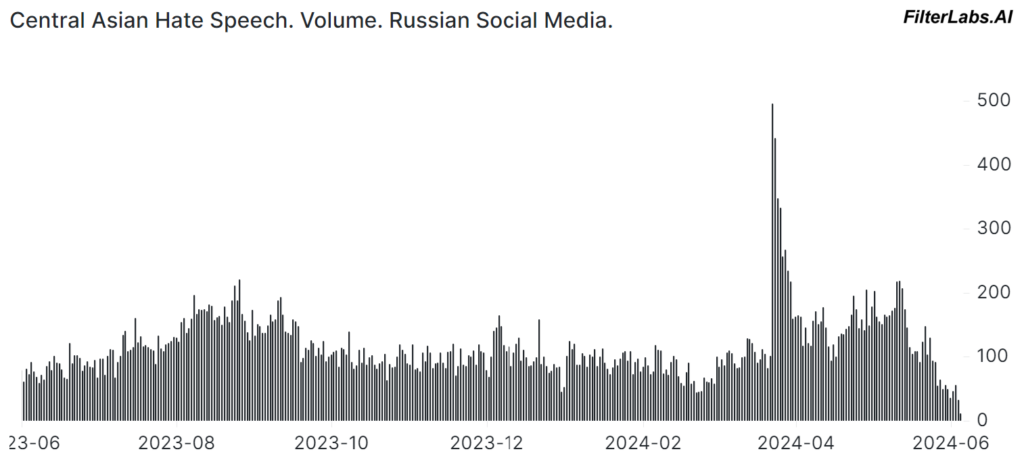

The graphs below that are based on the data from FilterLabs platform, show the volume of hate speech (in this case, ethnically motivated insults) directed against migrants from Central Asia and the Caucasus in Russian media and social networks. The March spike in both cases is a reaction to the terrorist attack at the Crocus City Hall, but the volume of such content in social networks shows a more stable pattern, indicating, among other things, the organic nature of content distribution. We believe that despite the presence of a large number of bots/trolls in Russian social networks and the fact that such anti-immigrant content is manufactured by Russian propaganda, it does find an audience among Russian-speaking Internet users. While the March spike is certainly an anomaly, other months also show significant amounts of anti-immigrant content, with pro-Kremlin media appearing less xenophobic than the discussions on Russian-language social networks.

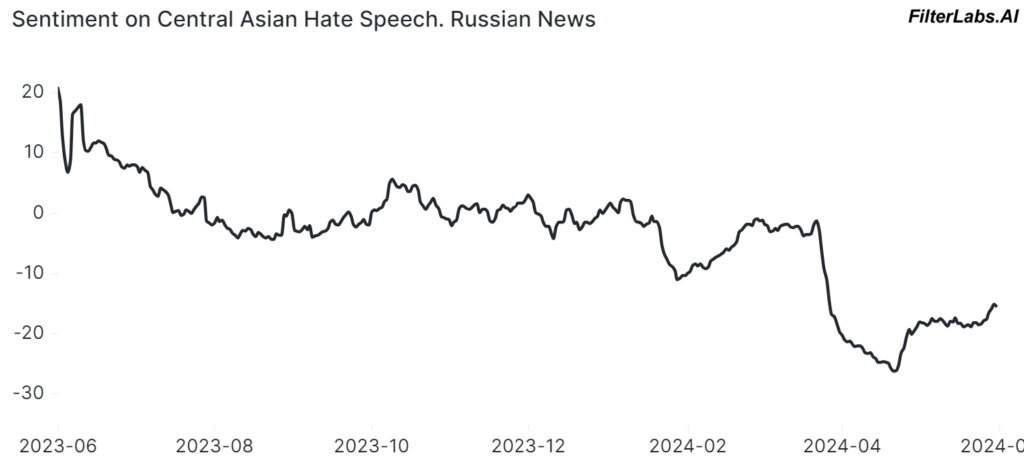

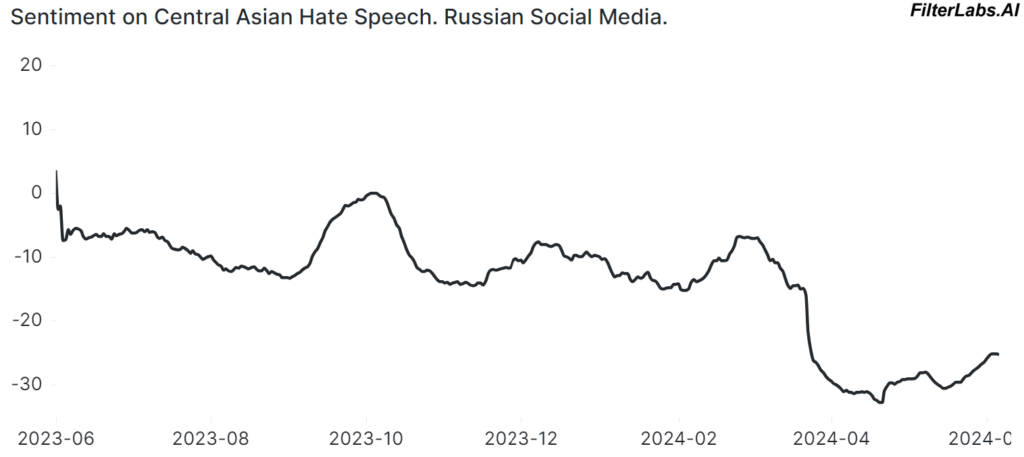

This is also confirmed by the analysis of the tone of the content: on news sites it is less negative than in social networks (on the graph, neutral tone is represented by zero, deviations in values with a minus sign — negative tone). In the graphs below we can see that the tone of content in social networks in relation to immigrants is consistently in the «negative» zone.

Prejudice against immigrants is also recorded in public opinion polls. Thus, according to an April poll conducted by the Levada Center, only 6% of Russians are willing to see natives of Central Asian countries as their neighbors, and only 17% do not mind if they come and settle in Russia (in April 2022, the figures were 10% and 28%, respectively, which are also low figures). At the same time, 31% of respondents said that if it were up to them, they would not let any Central Asian migrants come to Russia at all, while 26% said they would let them come «only temporarily» (in 2021, these answers were given by 15% and 27% of respondents, respectively). The majority of Russians also spoke in favor of limiting the flow of illegal migrants.

In general, we see that anti-immigrant sentiments in Russian society are not so much provoked as fueled by pro-government media and official discourse. That is why Russian society accepts additional restrictive measures against migrants and does not denounce widespread violations of migrants’ rights. The same cannot be said about another initiative that was launched in the information space after the terrorist attack in Crocus City Hall.

Should there be a moratorium?

From time to time, Russian propagandists raise the possibility of reinstating the death penalty, but after the March terrorist attack this issue was taken up by certain public officials. For example, Leonid Slutsky, head of the Liberal-Democratic party (LDPR), said in an interview with the Rossiya 24 TV channel: «All those who committed this unbelievably heinous terrorist attack must certainly be destroyed, we have withdrawn from the Council of Europe, we are no longer bound by any […] moratorium on the death penalty. And here there is only death for death.» The leader of the «Just Russia» party Sergey Mironov made a similar statement, noting that «the death penalty must be restored for terrorists. These sub-humans cannot live on our planet.» As early as March 26, this issue was discussed in the State Duma, but no consensus was reached about it. It seemed that the issue had naturally disappeared from the public agenda, but at the end of June it was raised again by the Chairman of the Investigative Committee of the Russian Federation, Alexander Bastrykin. Speaking at the plenary session of the International Youth Legal Forum in St. Petersburg, Bastrykin said: «It is necessary to consider the possibility of abolishing the moratorium on the death penalty. In some cases it should be used, and in these cases I am in favor of the death penalty».

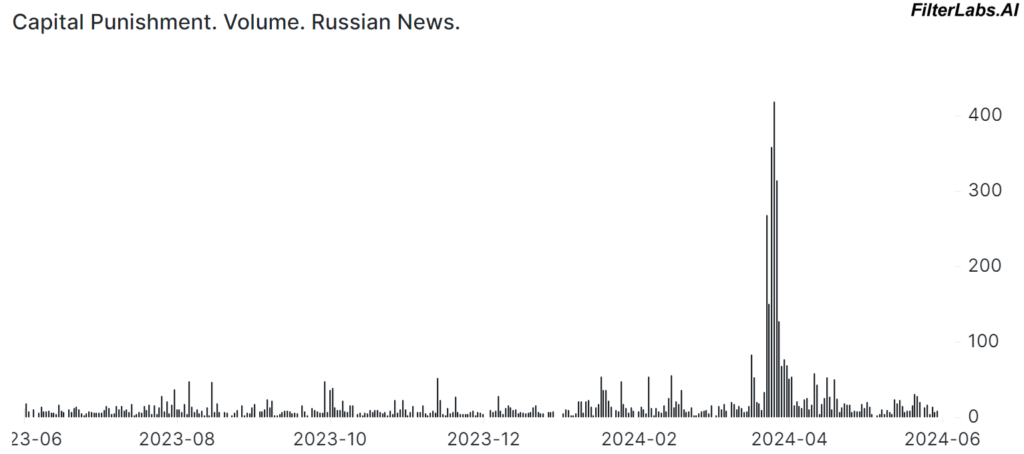

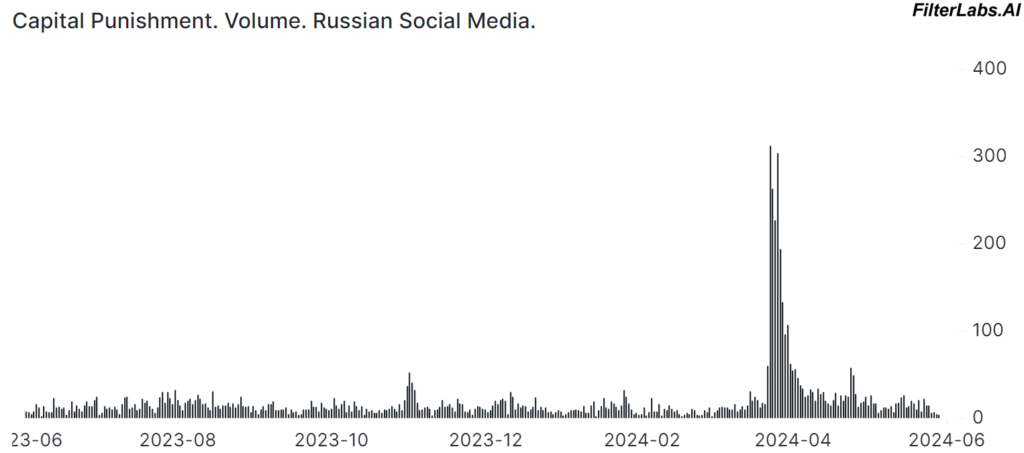

In the charts below we can see that until March of this year the issue of the death penalty in Russia was virtually absent from the public agenda: it was rarely raised in the media or discussed in social networks. The sharp increase in the volume of content related to the potential return of the death penalty observed in March is an anomaly dictated by external influences, in this case, it is a consequence of artificially inflating the issue from above. However, the rapid loss of interest in both social and mass media indicates that the issue has not taken root in the public imagination. Moreover, the attitude of the Russian elite to the subject is far from clear. For example, Valery Zorkin, Chairman of the Constitutional Court of the Russian Federation, stated, that «the moratorium on the death penalty in Russia is inviolable.»

At the same time, we notice that the debate on the death penalty imposed from above has not had a serious impact on public opinion. According to the Levada Center, after the terrorist attack, 52% of Russians were in favor of reintroducing the death penalty, while 36% were against it. In May 2021, we saw a similar ratio: 57% in favor to 37% against. Over the three years, the share of active supporters of the reintroduction of the death penalty decreased by 5 percentage points (the redistribution was due to an increase in the share of the undecideds). Thus, the discussion that has developed at the top of the power vertical is not yet reflected in the opinion of Russians and does not attract their attention. However, this does not guarantee that the power groups promoting the «return of death penalty» agenda will not try to bring this issue back into the public sphere. However, it is much more difficult to create interest from scratch than to strengthen an already existing interest (as in the case of the anti-immigration campaign). There are still some limits to how effective the Russian propaganda can be.

The author wishes to thank FilterLabs for providing this data. FilterLabs has recently launched Talisman, a platform that uses AI capabilities to analyze hyperlocal conversational and behavioral data