Among other things, Russia has generated a crisis in commercial aviation since the start of its war against Ukraine. Foreign lessors demanded that Russian airlines return 515 planes, which the Kremlin refused to do, and the planes were seized (or appropriated) from their owners. Lessors were able to reclaim only 78 airliners which landed abroad.

At the same time, Boeing and Airbus, as well as Embraer, Bombardier and aircraft engine manufacturers, have discontinued the supply of parts and maintenance services to Russian airlines. It is noteworthy that, as of 17 February 2022, Russian airlines were operating about 750 foreign-made aircraft (with Boeing and Airbus accounting for more than 320 and more than 330 planes, respectively), not counting light commercial aircraft and helicopters. Yes, that accounts for 55%-58% of Russia’s total fleet of aircraft prior to the war, which included between 1,290 and 1,367 planes (or 64% if all foreign models, including light aircraft, are taken into account). They accounted for the lion’s share of commercial passenger air travel within Russia and abroad. This forced Russian airlines to openly announce their transition to the practice of ‘aviation cannibalism’, whereby part of their fleet is decommissioned and serves as a source of spare parts for operational aircraft.

Against this backdrop, the Russian authorities are trying to convince everyone, including themselves, that Russia is self-sufficient in terms of manufacturing the number of aircraft it requires. Plans to become fully independent from imports of parts for the serial production of the Sukhoi Superjet (SSJ-100/RRJ-95) and the Irkut MS-21 were formulated before 2022. In addition, it was announced that there would be an increase in the production of the Tupolev Tu-204/214 and Ilyushin IL-96, developed in the late 1980s and less dependent on imported components. However, the authorities intend to finish phasing out the import of parts for these planes in 2023, although this was initially planned for 2020.

The actual situation in the industry proves, however, that the optimistic political rhetoric is unjustified. If the current restrictions remain in place for long, which seems very likely, Russian airlines, together with the authorities, will have to find ways to circumvent the embargo on imported aircraft parts and remodel the entire system of passenger air transportation in the country.

Volumes of passenger traffic

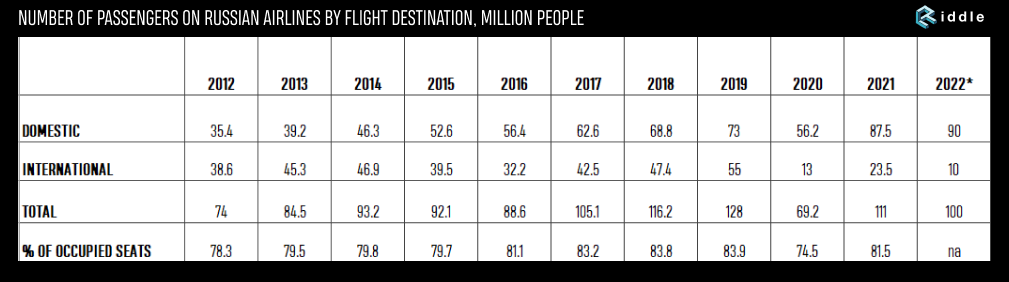

In order to analyse the future of Russian passenger air travel under the current conditions of tough sanctions, one should start with the number of passengers. As can be seen from the data for the last 10 years, domestic passenger traffic has outstripped international traffic in Russia since 2014. After a decline in 2020, domestic traffic peaked in 2021 amid the closure of many foreign destinations and a boom in domestic tourism. At the same time, the total number of passengers in 2021 recovered, reaching a level comparable to that of 2017−2018. This year it is likely to drop again.

Thus, given current and projected volumes of domestic and international air traffic, Russian airlines definitely have spare aircraft that can be used for parts without compromising the in-country destination network, at least in 2022, and possibly beyond. In addition, the load factor peaked in 2018−2019. Today, there is some room left when it comes to the number of passengers on board Russian airlines. Consequently, there is still room for aviation cannibalism.

Still, it is doubtful that Russian commercial aviation will operate like that beyond 2023. The question arises whether the Russian industry is able to make up for the withdrawal of foreign aircraft manufacturers from the Russian market.

Is it possible to bring the old guard back to life?

Under the de facto embargo on imports of modern European, American, Canadian and Brazilian aircraft into Russia, the idea of increasing the production of airliners, developed in the 1980s, seems logical. We are talking about the narrow-body Tupolev Tu-214 and the wide-body Ilyushin Il-96. After all, Russian government agencies order and operate these aircraft, as do airlines in North Korea and Cuba. However, as few as two Tu-214s were produced in 2020−2021 after a break of several years, and two IL-96s did not take to the air until 2021, although they were expected to begin flying in 2015.

Despite this, the management of the United Aircraft Corporation (UAC) announced plans to deliver 20 Tu-214s as soon as possible. It seems that we are talking about using material stocks from previous years, which will suffice for this number of airliners. Plans for a total of seventy Tu-214s by 2030 were also voiced, which means annual production of 8−10 planes starting from 2023, when the production of all the required parts will take place in Russia.

As for the IL-96, UAC management has much more modest ambitions: the plan is to build at a pace of two planes a year, which means the construction of a maximum of 16 aircraft by 2030.

At the same time, it is not clear who will manufacture these planes. For example, the Aviastar plant in Ulyanovsk, which manufactures the IL-76MD-90A military transport aircraft and potentially has some spare capacity to produce the Tu-214, needs 1,500−2,000 employees in 2022 alone, in addition to the 8,500 workers it currently employs, and only for the military order for the IL-76. In total, it needs to increase its staff to 15,000. Currently, UAC needs an additional 8,500 people to assemble the planes (apart from support personnel and additional administrative staff). With the total headcount at 83,000 people at the end of 2021, this means an increase of more than 10% among highly qualified personnel. Simply put, there are staff shortages when it comes to building new old planes.

And even if we assume that full in-house production is maintained and qualified staff can be found, it’s all about the engines. The Perm Engine plant [Russian: Permskiye Motory], which manufactures PS-90A engines for the IL-76 (a quadjet), the IL-96 (a quadjet) and the Tu-214 (a twinjet) also has its limits. As of 2017 (no more recent data are available today), this plant produced twenty-five new PS-90A engines, as well as thirty-two PS-90A-based industrial gas-turbine power units. Taking into account that the Aviastar plant has been trying to boost the output of the IL-76 for several years, from 3 to 12 or at least up to 10 aircraft per year, the Perm Engine plant needs to produce forty PS-90A engines annually, not to mention spare engines. If we add ten Tu-214 and two Il-96 planes per year, at least 28 more engines are needed.

It turns out that the Perm Engine plant has to reach annual production of at least sixty-eight PS-90A aircraft engines. And this is despite the fact that the main task of the plant today is to launch serial production of PD-14 engines for the MS-21 airliner. In other words, even the forecast seventy Tu-214 and sixteen Il-96 planes by 2030 seems to be an unachievable task for the Russian industry today.

Flagship aircraft without international cooperation

Russia has long banked on the following projects: the SSJ-100 and IL-114 regional aircraft and the MS-21 medium-range aircraft. Of these three projects, only the SSJ-100 is in serial production. The production rate is uneven: at its peak in 2014, 35 aircraft were built, and in 2020 and 2021, 11 and 12 aircraft were produced, respectively. Currently, the plan is to reach 20 aircraft per year with a total forecast of 150 new SSJ-100 planes by 2030. In 2022 this target will not be reached. Taking into account the fact that there are about 25 more planes in storage at the factory and with some Russian airlines, this 2030 forecast looks feasible. Given existing sanctions, however, the Superjet needs a replacement for the SaM146 engine, produced through currently non-existent French-Russian industrial cooperation, in the form of the Russia-produced PD-8 engine. There is an additional problem here. Namely, this engine does not exist yet, and in the best-case scenario it will not be ready for mass production until 2024 at the earliest. The SSJ-100, which Russia is going to build before that time, will be built using previously amassed stocks of imported components. Consequently, the rate of production of this aircraft in the mid-2020s cannot be predicted today.

As for the Ilyushin IL-114 regional turboprop airliner, the Russian authorities were going to start serial production in 2021, taking into account the imports phase-out. However, today we are already talking about 2025 and the production of no more than 12 aircraft a year. Thus, even the most optimistic scenario envisages that Russian airlines will have no more than 70 of these planes in 2030. In reality, there will be even fewer of them.

The fate of Russia’s most ambitious project, the MS-21 plane, which is in the same class as the Boeing 737 and Airbus A321, is also unclear. First, its serial production will not begin until 2024−2025, due to the discontinuation of cooperation with foreign suppliers. Second, the planned pace of this production is not very clear. For example, less than a year ago Deputy Prime Minister Yuri Borisov spoke about reaching a production level of 36 planes per year. The head of Rostec Corporation, Sergey Chemezov, said in early 2022 that there would be seventy-six MS-21s in 2027 (perhaps, he was referring to their total number by then). In turn, UAC CEO Yuri Slyusar announced in April 2022 that there would be thirty-six MS-21 aircraft per year in 2025, with a subsequent increase in annual production to 72 units.

However, promises given by Russian officials and top managers of state corporations are undermined by the Perm producers of the PD-14 engine for the MS-21. The Perm Mashinostroitel plant is capable of producing 16 sets of components for this engine to meet the needs of the Perm Engine plant, with an increase in production to 20−25 sets in 2025. Currently the Perm Engine plant is capable of producing one PD-14 engine every 20 days, and promises to reach 50 engines per year in the future. Putting aside spare engines, this will ensure the construction of no more than twenty-five MS-21s per year in the foreseeable future since this aircraft was initially to be equipped with Perm PD-14 or American PW1000G engines, as indicated by the customer. Thus, even 36 aircraft in the next few years is unrealistic.

Subsequently, in the best-case scenario, Russia can be expected to produce about 350 commercial airliners by the end of the 2020s. That is, in theory, it can replace only less than half of its existing fleet of foreign aircraft. Cannibalism alone will not suffice. Russia will instead choose to bypass aviation sanctions in the near future — for example, by buying spare parts or even old airliners from major airlines in Asia and Africa.

In addition, it is possible to expand the practice of complex inter-regional flights where an aircraft makes intermediate stops along its route, covering a larger number of airports, as, for example, is practised by Azimuth, an airline flying the SSJ-100. It also seems logical to bolster the role of major regional airports, where passengers will be transferred from one SSJ-100 or IL-114 aircraft to another instead of using American or European aircraft for direct flights of several thousand kilometres. At the same time, upgraded inter-regional railway and bus services will be offered to the regions whose standard of living will be deteriorating faster. Admittedly, railway and bus services have not been expanded in recent years or have actually been cut. In any case, Russian aviation cannot be expected to operate successfully without foreign aircraft.