The Kremlin has finalized the list of the appointed chairmen of the parliaments of the newly occupied territories of Ukraine and their representatives in the Council of the Federation. These appointments show that the Russian authorities have been unable to devise a unified policy for these territories and establish principles of relations with their elites, who have agreed to cooperate with the Kremlin. The chairmen recruited for the people’s councils have various professional backgrounds, yet they do not have any serious status in either Russia or Ukraine. This suggests that the Russian authorities are not very confident about their prospects in the areas of Ukraine occupied by the Russian army, and are creating lightweight easy-to-assemble-and- dismantle structures rather than long-term institutions.

The most striking appointment among the chairpersons of the people’s councils of the Ukrainian territories annexed by Russia last year was the election of the Sparta Battalion commander Artem Zhoga as chairman of the parliament of the self-proclaimed Donetsk People’s Republic. Zhoga is a local who has been fighting in separatist battalions, including Sparta, since 2014. This unit was first led by one of the most media-savvy figures of the Donbass war, Arsen ‘Motorola’ Pavlov, and after his death in an elevator explosion, he was succeeded as the commander by Vladimir Zhoga (the late son of Artem Zhoga, who in turn took over the battalion after his son’s death). The Russian media present this appointment of Zhoga as a chairman of Donetsk «parliament» as a symbolic step to commemorate the fallen members of the separatist forces and honour the participants of the war with Ukraine. Of course, Zhoga has no political experience (and even no college degree). His appointment could speak of the Kremlin’s deliberate militarisation of its policy in the annexed territories. However, in other regions it is not the people in uniform who have been picked to become chairmen of people’s councils.

In the self-proclaimed Lugansk People’s Republic, Denis Miroshnichenko, previously a municipal deputy from the Party of Regions and head of a municipal enterprise, was reappointed chairman. In the Kherson region, the people’s council loyal to Russia will be headed by Tatyana Tomilina, who until 2015 was the director of the Mishukov Academic Lyceum at Kherson State University and after the invasion of the region by the Russian army became the rector of the University itself. Viktor Emelianenko was appointed the chairman of the «parliament» of the territories annexed by the Kremlin in the Zaporizhzhya region. In Ukraine, he was an official of the Party of Regions, deputy governor of the Zaporizhzhya region until 2014, and after the full-scale invasion of Russian troops in 2022, he returned to this post.

In parts of the newly occupied Ukrainian territories Kremlin has considered carpetbaggers, «imported» from Russia to run for the offices of chairpersons of the people’s councils in some of the occupied territories. For example, the Zaporizhzhya «regional council of deputies» could be headed by Roman Batrshin, former deputy chairman of the Smolensk regional court, and the Kherson parliament could be headed by Igor Kastukevich, now a former United Russia State Duma deputy from Voronezh and former head of the youth organisation of the All-Russian Popular Front (he eventually became the senator representing Kherson regional council). There were also speculations of Russian political technologist Sergei Tolmachev (now working as vice-governor of the annexed territories of the Zaporizhzhya region, before this appointment he was deputy head of Sevastopol) potentially becoming the chairman of Zaporizhzhya’s people’s council. Renat Karchaa, a political technologist from Rosatom, was also on the «United Russia» party list for the Zaporizhzhya elections. He, too, is a logical candidate for the post of the council’s chairman. In addition, Kremlin officials ran for people’s councils on the «United Russia» party lists, with the hypothetical expectation that they would be more than just ordinary MPs. As a result, the Kremlin’s political bloc opted in favour of local collaborators. This logic cannot be explained by appealing to popular figures: neither Tomilina nor Emelianenko had ever been elected to any significant public office before, not even during Viktor Yanukovych’s time in the office. Obviously, Kremlin officials chose the usual logic of appointing chairpersons, occasonally picking vice-governors for domestic politics or university rectors for that job. In other words, the appointment formula was simple: let’s do it «the way it is done in Russia», according to a template, without regard to the real authority and popularity of the selected chairpersons. However, there are hardly any popular figures among the MPs themselves. It is symptomatic that the heads of the pro-Russian administrations of the municipalities in the annexed territories did not become chairmen either.

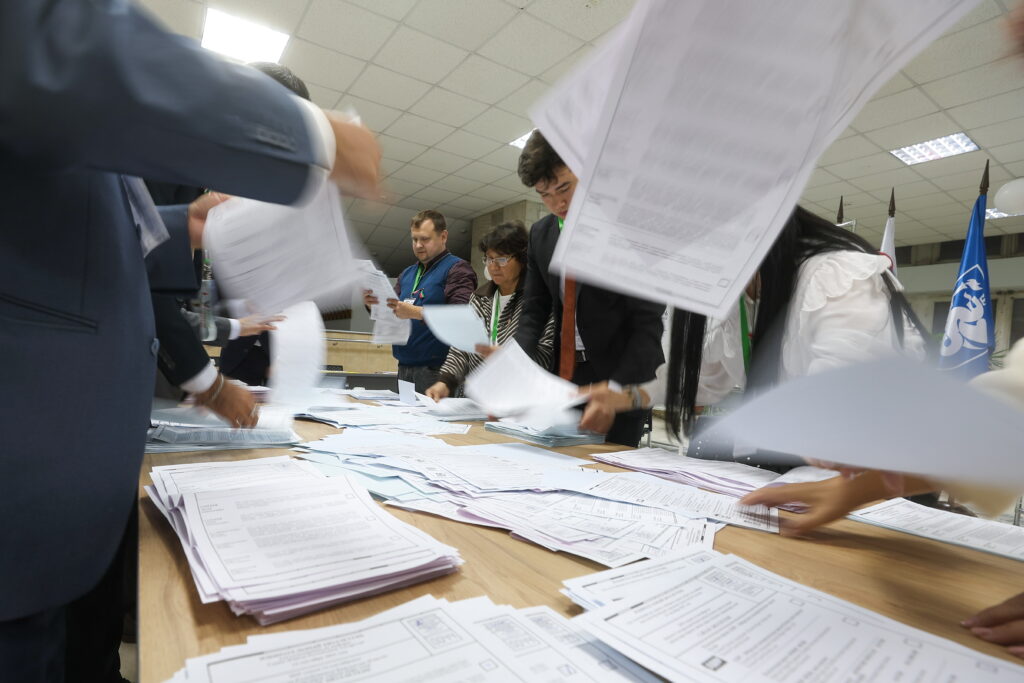

The Kremlin’s decision not to use «imported» chairpersons (although this practice has been used in certain Russian regions) and the reluctance of municipal officials, who now manage real financial flows, to take charge of the local «parliaments» is very indicative of these «parliaments”‘ real political weight and the seriousness of the plans that the presidential administration has for them. The local actors who have been given the opportunity to manage budgets, invariably opt for money not the office of the council’s chairperson, which means that they do not believe that this position carries any serious political weight or influence. Carpetbaggers who had time to work in the territories could also refuse the position of a chairperson after assessing its real clout and future prospects. The presidential administration chose not to force either the locals or the «imported candidates» to run for the offices of council chairperson, which could mean that the Kremlin had no special plans for these parliamentary assemblies either. It turned out to be enough for the Kremlin to formalise the election of these nonames into local «parliaments» with supposedely impressive figures of support (the «United Russia» party is said to have won an average of about 80% of the votes in the annexed territories) and to put in charge some obscure personalities with only a formal status of a «university rector» or «vice-governor» to their names. It is clear that Moscow has no serious intention of creating a loyal elite, pushing it into MP’s seats, luring it with positions or importing this elite to the newly annexed territories on the permanent basis. Rather, the councils were created for the sake of accountability: their existence is required by Russian law, so the political bloc of the presidential administration had to hastily set them up. All the more so because the main commissioner of all these efforts — the president — is not interested in anything other than the ruling party’s impressive results on paper.

The «parliaments» of the annexed territories turned out to be easily assembled constructions in which the Kremlin did not bother to include elements of at least some weight and perspective. This means that these constructions can be easily dismantled if, for example, the Ukrainian counter-offensive succeeds. The Kremlin has clearly decided not to involve politicians and officials with any prospects in the formation of Russian-controlled parliaments, and has similarly approached the appointment of heads of the annexed territories.

Local actors mostly remained in these offices, often without much authority. Consider, for example, Denis Pushilin, a former MMM (one of the world’s largest ponzi schemes) employee and ‘head’ of the Donetsk People’s Republic. Last year, however, there was a serious discussion of whether they should be replaced with federal politicians or not. Nor does the presidential administration make any effort to develop its own cohesive policy in the occupied territories and instead relies on a patchwork of various artificial models. The deliberate exaggerated militarism of the Donetsk People’s Republic bears little resemblance to the stagnant Soviet-type realities of the Lugansk People’s Republic, and in the areas of the Zaporizhzhya and Kherson oblasts occupied by Russian troops no such models have emerged to begin with. At the same time, the regions of the Far Eastern Federal district, which have been the focus of the Kremlin’s attention for several years now, have such common features: their leaders create various territories of advanced development, hold festivals and forums in order to keep the Kremlin’s attention on themselves. The creation of a separate district for the Donetsk People’s Republic, Lugansk People’s Republic, Zaporizhzhya and Kherson regions, which was discussed last year, has also lost its relevance.

The Russian authorities have not yet found an alternative to the «rotation shift method» in the development of the annexed territories. The managers imported from Russia work in the governments of the annexed territories and can easily be removed from their offices and returned to their former positions or positions of equal status. Being a council’s chairperson implies a more serious attachment to the place, and no one wants to take that risk. Federal politicians who worked in the Donetsk People’s Republic, Lugansk People’s Republic, Zaporizhzhya and Kherson regions are gradually moving to federal positions. As we have mentioned earlier, Igor Kastukevich, an MP and a «United Russia» party curator of the Kherson oblast’, became a senator from this region. Back in December, a former member of the presidential administration Darya Lantratova was confirmed as a senator from the self-proclaimed Lugansk People’s Republic (her time in the office was extended this year). Dmitry Rogozin, a former deputy prime minister and ex-head of Roscosmos, who in the early months of the war had hoped to become head of a federal district that the Kremlin wanted to create on the basis of the annexed territories, also left to become a senator. The district was never created, and there was no other position for Rogozin.

All this means that the Kremlin is not very confident about its prospects in the annexed territories and is not yet trying to establish real working structures there, confining itself to formal and chaotic copy-pasting of established Russian practices.