The most interesting month for anyone tracking the Russian budget is always December. For instance, in the final month of 2022, expenditures unexpectedly jumped from 24 trillion rubles to 31 trillion rubles, completely changing the fiscal balance for the year. Thus, it may seem risky to analyze how 2023 played out already in November. Even so, the overall story for the year is already clear: A weaker ruble has left Russian revenues 10% higher than planned in the original budget law for 2023. On the other hand, expenditures have also increased by around 10%, leading to a deficit that looks similar to the Finance Ministry’s original projection of 2% of GDP. At the Valdai Forum in October 2023, Putin even predicted a better outcome of 1% of GDP.

Under the surface of these numbers, somewhat hidden by internal spending shifts, war expenditure has accelerated in 2023. The planned increase of «Defense» spending to 10.8 trillion rubles in 2024 (6% of GDP) is actually not such a big jump, but rather a continuation of a pre-existing trend.

Budget revenues benefit from a weaker ruble

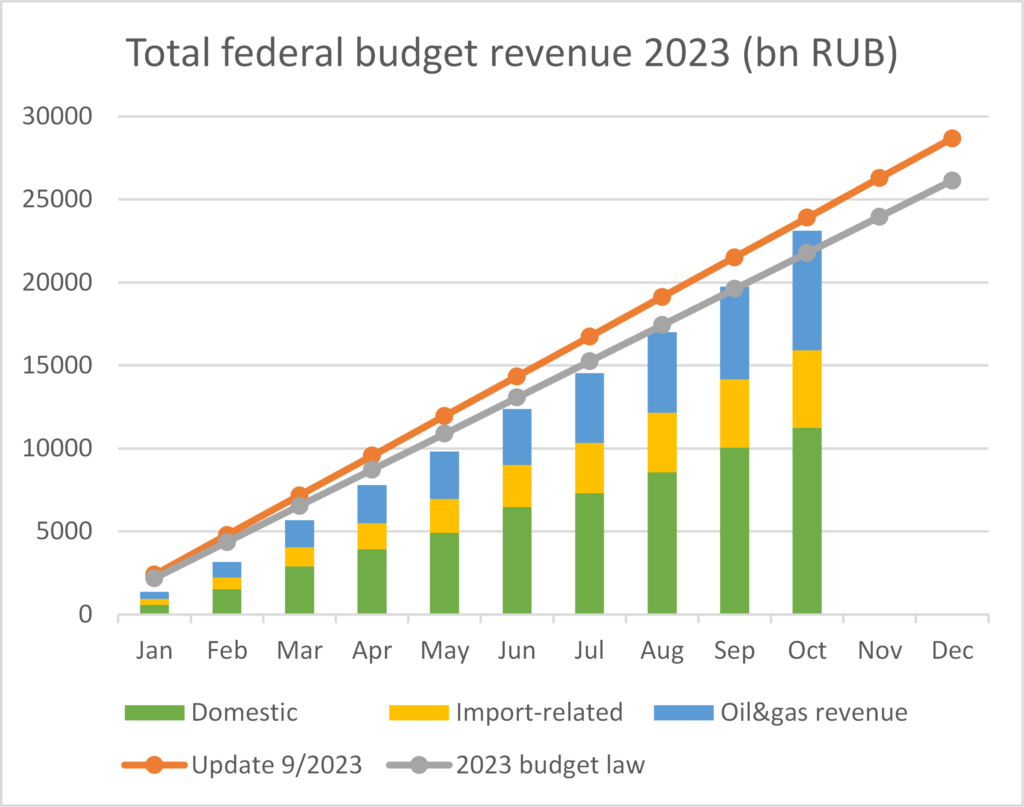

Although Russia’s budget revenue looked weak in the first months of the year, it began tracking the original estimates of the Finance Ministry closely later on and slightly surpassed them in recent months. This allowed Finance Minister Siluanov to raise the estimate for 2023 federal budget revenues by 10%, from 26.1 trillion rubles to 28.7 trillion rubles in the process of drafting the new budget law for 2024 (by 1.6% of GDP, see table at the end of the article).

Domestic taxes (such as VAT, excises, income and profit taxes) behaved almost exactly as predicted in the budget law for 2023. The more interesting part of the revenue side was everything related to trade. There was much more fluctuation in Russian tax revenue related to oil and gas exports and also import-related taxes.

Both import- and export-related revenues are benefitting from the weak ruble. The Finance Ministry originally expected an average exchange rate of 68.3 USD/RUB in 2023. In the latest documents (published with the 2024 budget), it raised the estimate for 2023 significantly to 85.2 USD/RUB: On average, the ruble was 20% weaker than expected.

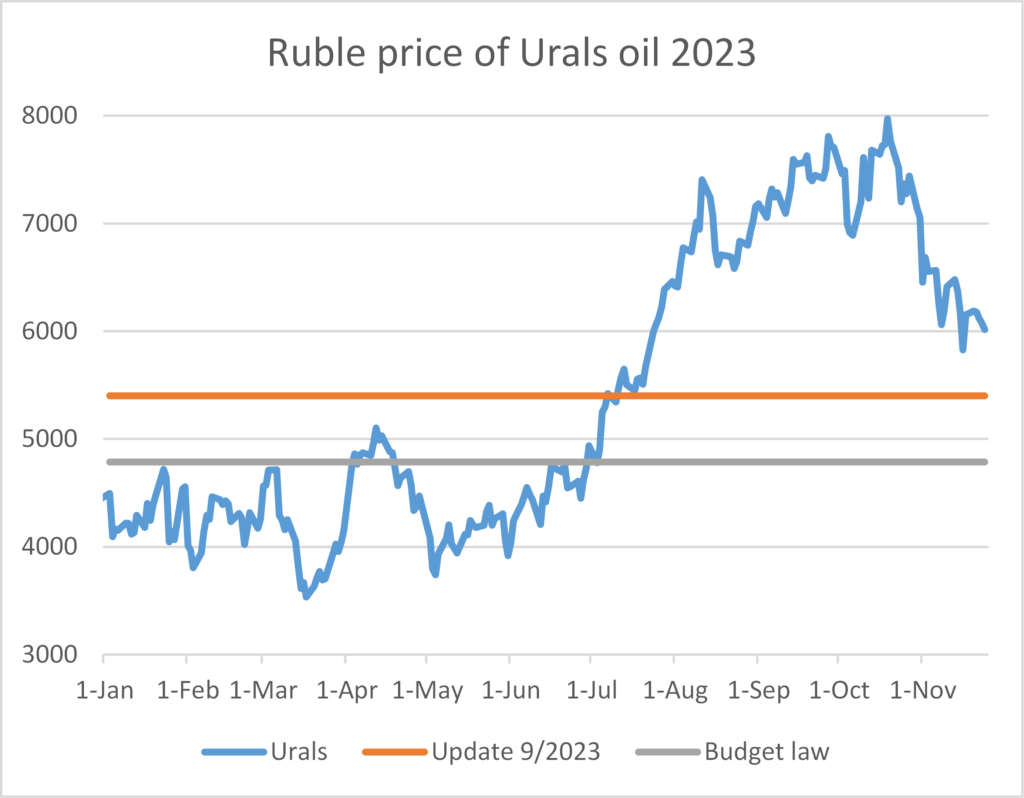

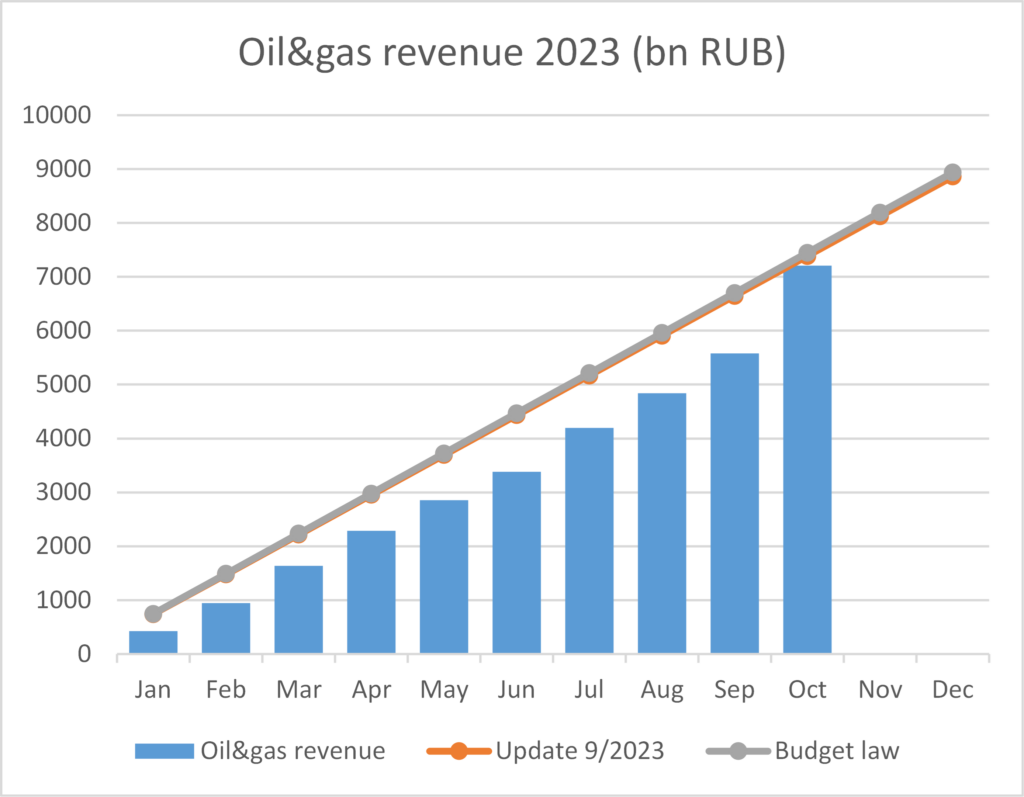

Russia’s budget revenues from oil and gas depend primarily on the Urals oil price expressed in rubles. A 20% weaker ruble means a 25% increase in the ruble price of Urals oil, if the dollar price remains the same. The dollar price for Urals oil was 10% lower than the Finance Ministry expected (63.4 instead of 70.1 dollars). This was mostly because of the EU oil import embargo, which had a temporary but painful effect on Russian revenues, because Russia had to find new (mostly Indian) buyers in a very short time. The oil price cap, a separate measure introduced by the G7 that tries to limit the price of Russian oil sold to non-sanctioning countries, made the logistics of re-orienting Russian oil trade more difficult, but has had limited effect at best after the winter.

Despite the sanctions, the weak ruble meant that the resulting oil price in the Russian currency was higher than expected (5,400 instead of 4,800 rubles). This also compensated for the fact that Russia reduced its oil export volumes to stabilize Urals oil prices under pressure from sanctions. Russian oil and gas revenues will come in very closely to the original target of 8.9 trillion rubles.

Meanwhile, the rollercoaster of oil revenues is set to continue. Due to a fall in global oil prices in late 2023 that coincided with Russia’s attempts to strengthen its currency with capital controls, the ruble price of Urals oil fell 25% from its October highs (from 8,000 to 6,000 rubles). While it is too late to significantly impact the 2023 budget, because mineral extraction tax revenues always trail the price developments by 1−2 months, oil revenues can be expected to weaken again into next year.

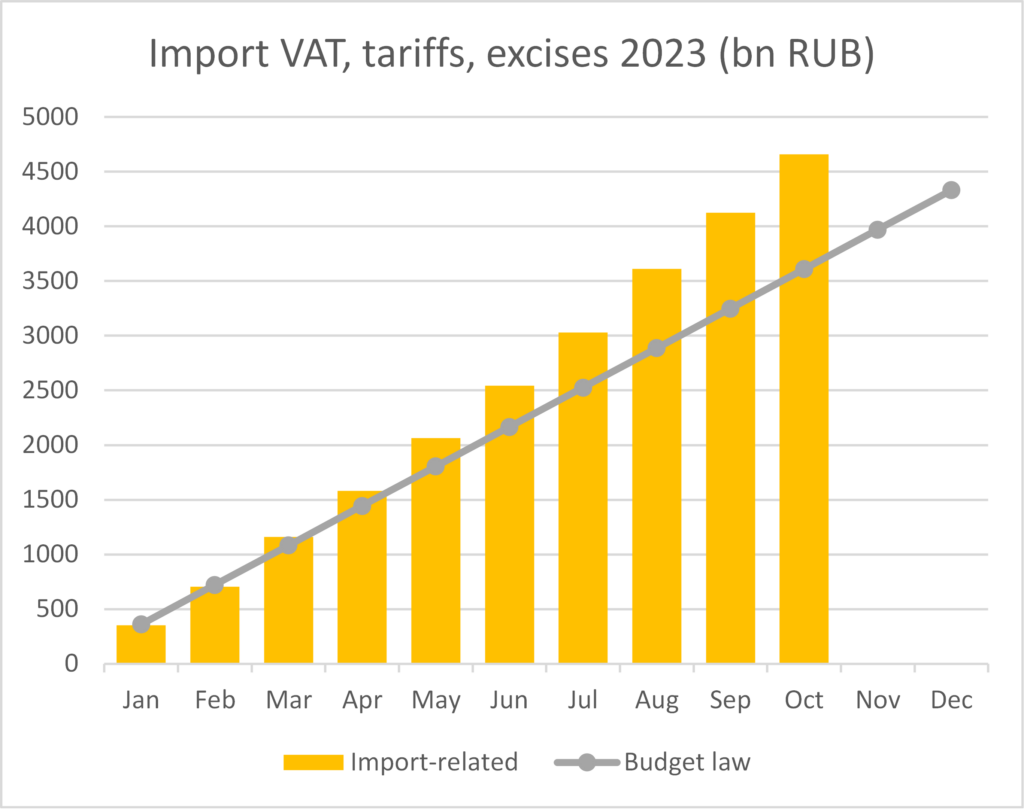

While the weak ruble brought Russian oil and gas revenues back in line despite sanctions, it also boosted another type of revenues: Taxes collected on Russian imports — such as VAT on imports, excises and import tariffs — exceeded intial projections and are responsible for most of the increase in total revenue in 2023.

Russian imports have been stronger than expected in 2023, as budget spending was fueling demand while the economy was running at record capacity utilization. Domestic production simply could not keep up, leading to more goods being imported. The original import estimate in the budget law for 2023 was 288 billion US dollars. The Russian government updated this estimate to 314 billion US dollars its latest estimate. Additionally, the weaker ruble was a boost for the budget: Expressed in rubles, imports were a whopping 35% higher than expected. The fact Russians are paying a higher price for imported goods directly benefits the Russian fiscal situation: Import-related tax revenues were already 1 trillion rubles higher than expected in October 2023. This windfall will certainly further increase in November and December, meaning import-related tariff revenue will add almost 1% of GDP in unexpected tax revenues to the budget.

The war is driving up budget spending

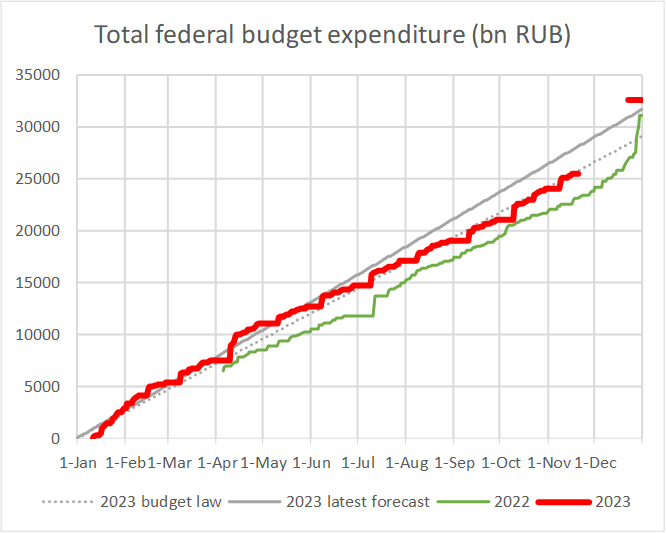

Unless something unexpected happens in December, Russia’s federal spending will end up between 32 and 33 trillion rubles for the full year of 2023. In the process of planning the 2024 budget, the Finance Ministry updated its forecast for 2023 revenues from the originally budgeted 29 trillion to 30.3 trillion. The even more up-to-date website of the Electronic Budget already shows an expected 32.6 trillion rubles. Hence, expenditure in 2023 could be over 3.5 trillion rubles (2% of GDP) higher than originally planned in the budget law. While spending leveled off after a surge in the first half of the year, historical patterns predict a strong December.

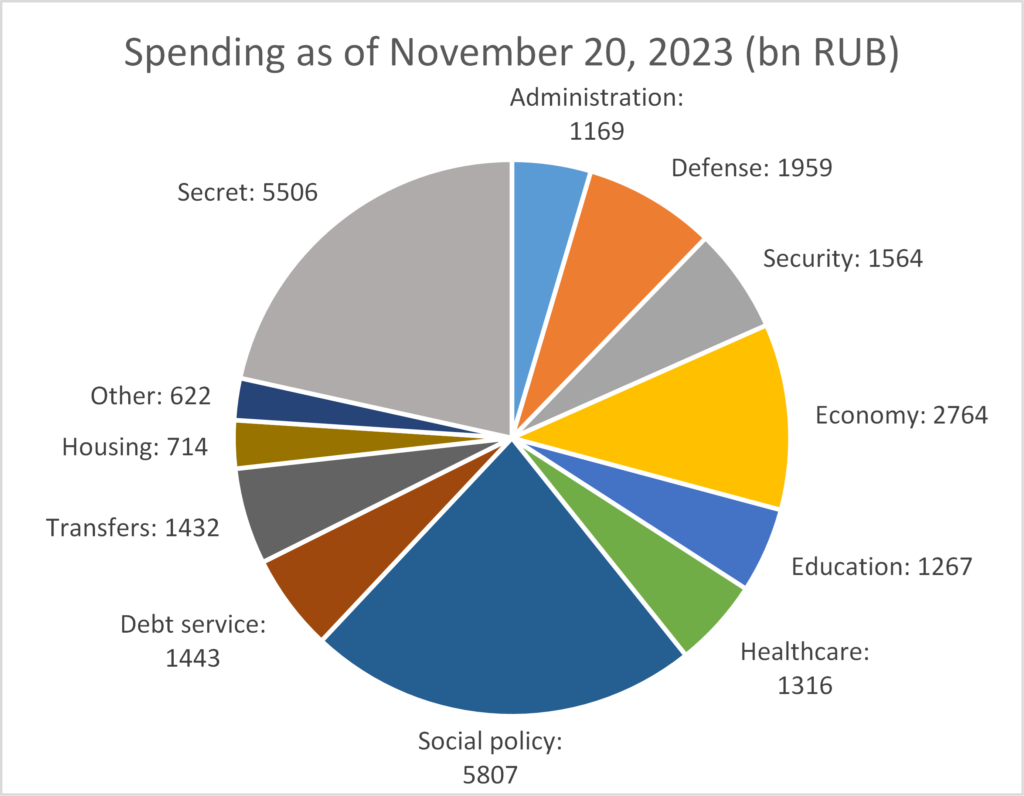

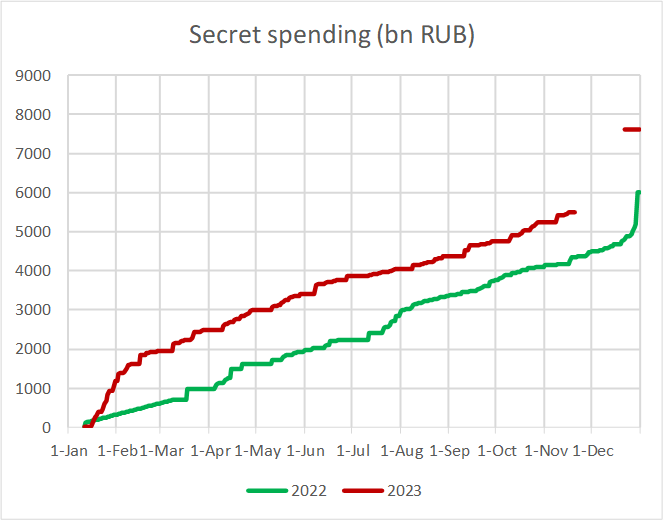

As of November 20th, almost 22% of Russia’s budget expenditure for the year is secret. Over 2/3 of this secret spending traditionally belongs to the «Defense» budget. Nowadays, an even higher share is related to the war, but partly falls in other categories. Secret spending was particularly high in the first months of the year, contributing 33% to total spending in the first quarter.

Most civilian spending categories are predictable: They stay within the original budget projections and increase gradually over the course of the year. This is true for most types of social spending, such as «Social Policy», «Healthcare» and «Education».

While expected spending on «Security» was reduced over the course of 2022 (from 3.6 to 3.2 trillion rubles) and so far seems to remain below even this lower figure, there are two other categories that have shown clear increases related to Russia’s war: «Housing» and «Transfers».

«Housing» includes the construction and maintenance of public buildings. In 2020, spending in this category was 372 billion rubles. In 2023, it is expected to be 847 billion in the latest projections, a strong increase when compared to the already high 591 billion in the original budget for this year. A closer look at spending subcategories (quarterly budget reporting is still very detailed) reveals that this sudden increase is related to spending on frontal regions and annexed territories. The situation in «Transfers» is similar. This category mostly consists of subsidies to regional budgets, which usually follow strict a predictable formula. This year, there was a sudden increase from 1252 billion to 1530 billion rubles. Again, a closer look reveals that this increase is related to construction activities close to the frontline.

The trillion-ruble question (quite literally) in the 2023 budget is if secret spending will skyrocket again in the last days of the year, similar to the end of 2022. The Finance Ministry claimed in early 2023 that the high spending in the first months of the year will avoid an extreme December like in 2022, but given the unpredictable nature of war spending, the Finance Ministry may find it hard to predict spending itself. Depending on the final days of the year, secret spending will most likely range somewhere between 6.5 and 7.5 trillion rubles, clearly exceeding last year’s level of 6 trillion rubles.

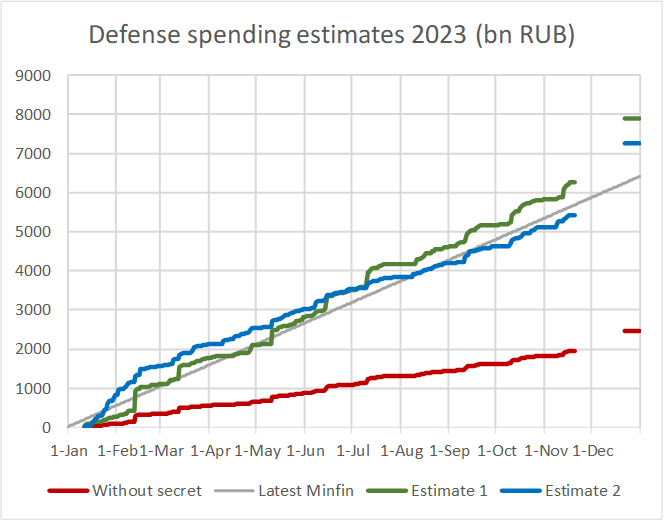

Based on historical patterns, it is possible to estimate the amount of secret spending that is connected to «Defense» spending in two different ways:

One way to do this is to start from the published amount of defense spending and multiply it with a factor that is derived from last year’s data (last year, total defense spending was 3.2 times higher than published defense spending). The result is «Estimate 1» in the following chart.

The second way is to use the current level of secret spending and distribute it across the other categories based on 2022 patterns (63% of secret spending belonged to the «Defense» category last year). The result is «Estimate 2» in the following chart. Both estimates are not far apart and predict total «Defense» spending between 7.3 and 7.9 trillion rubles for the year, around 1 trillion more than the Finance Ministry’s last estimate of 6.4 trillion rubles. Again, this is based on last year’s patterns, which may not repeat.

Russia’s budget weakened in 2023

On paper, the deficit in last year’s budget was 2.1%, while this year’s deficit is predicted to come in at 1.8% in the Explanatory Note attached to the new budget law. Even if the actual deficit is closer to 1% as Putin suggested, the underlying trend is still negative. The reason is that some of 2023 spending was already built into the 2022 budget.

2022 was an historically profitable year for Russia, as Moscow benefitted from high energy prices, which in turn were boosted by Russia’s own aggression — economics is often not fair. Russia used the comfortable budget situation to prepare. In 2022, the government allowed small- and medium-sized companies to defer their social security contributions, meaning less revenue for the state in 2022 and more in 2023 and 2024. In addition, the Finance Ministry made a prepayment to the «Social Fund of Russia» (pensions and social transfers) in December 2022, effectively transferring 1% of GDP from the 2022 windfall to 2023.

This is why the Finance Ministry’s itself estimates the «true deficit» (without prepayments and other distorting factors) for 2022 at 0.7% of GDP and the «true deficit» for 2023 at 2.7%. These numbers are a better representation of the Russian government’s ability to collect taxes and the spending requirements of the war and show that the situation clearly worsened in 2023.

The moment of truth in 2024?

In the wider economy, 2023 was a year marked by dynamic growth, driven primarily by Russia’s military industry. GDP growth in 2023 will most likely exceed 3%. In contrast, 2024 could become the «year of truth» for Russia’s economy in several ways.

The Finance Ministry hopes for significantly higher tax revenues (19.5% of GDP in 2024, up from 17.3% of GDP in 2023) to further ramp up war financing. More tax revenues would mean a partial reversal of the fiscal stimulus that boosted the economy over the last couple of years. In combination with a key interest rate of 15% and labor scarcity, businesses not directly producing for the war will face major headwinds.

This means that 2024 could also be the year when the price of the war will finally be felt more acutely by average Russians. Consumer prices have already increased by over 0.8% per month in September and October 2023, which is equivalent of a 10% annual rate. Until the presidential elections in March 2024, the government will certainly keep the ruble stable with the newly re-introduced capital controls, and keep budget spending high.

However, propping up the ruble today only leads to more downside pressure after the support measures end, and extra spending before the election means less spending afterwards. Furthermore, if the Central Bank is serious about bringing inflation down, it might have to drive Russia’s economy into recession to achieve that goal. While the Finance Ministry built its budget for 2024 around the expectation of 2.3% GDP growth next year, recent forecasts have already become much more pessimistic, and even a recession seems possible.

It is a commonplace to end any outlook for Russia’s economy with a disclaimer about the oil price. Since the start of the full-scale invasion, Russia has become much more vulnerable to oil price swings. If prices fall, the government would have to let the ruble devaluate drastically, leading to high inflation and quickly falling real incomes. Defending the ruble would become very difficult, even if the Central Bank wanted to do it, because Western sanctions limited the available currency reserves. The last time Russia went through such a period was in 2014−2016. In the following years, Russia consolidated its budget by cutting expenditures, including for the military, and raising the retirement age. In a time of ever increasing war spending, any fiscal consolidiation would be even more painful for the population.

The author thanks Bloomberg’s Alex Isakov for providing Electronic Budget data used in this analysis.