In December 2021, a draft law on electronic voting was introduced in the State Duma, and on 14 March, Vladimir Putin signed the adopted law. A few days before the final adoption by the Duma, two more sets of amendments initially unrelated to online voting were added to the draft law, namely the de facto elimination of the institution of non-voting members of electoral commissions and another extension of the number of registers of so-called foreign agents.

During Russia’s ‘special operation’, this sort of crackdown on citizens’ rights (in this case, electoral rights), which includes the introduction of amendments to draft laws without any public debate, has become the norm for Russian lawmakers. These amendments are unrelated to the draft laws under consideration. In May 2020, for example, provisions that greatly restricted citizens’ passive right to vote suddenly appeared in a technical draft law on possible changes to constituencies, and the amendments were immediately adopted.

Another lamentable tradition exemplified by the 2021 draft law is the annual weakening of the electoral law that takes place every year in spring, right before the start of campaigns for Russia’s single voting day — that is, usually between February and May or as late as June each year. For example, 2022 saw the adoption of amendments that abolished mandatory proportional representation in regional elections. Since then, there has been a dramatic reduction in or complete elimination of proportional elections across the country: such amendments to regional laws have been adopted in the Altai Republic, Chuvashia, Yaroslavl and other parts of the country. The electoral laws were weakened previously in the spring of 2021, 2020 and earlier.

Although the current legislative blitzkrieg was conducted with lightning speed, it did not come as a big surprise.

Online black box voting

The first set of legislative amendments adopted by the 2021 law were expected (in fact, these amendments were originally announced in December 2021). Thus, the law made electronic voting possible in any type of election in Russia. In January 2022, a group of experts submitted a 12-page review of the draft law, in which they pointed out that it lacked guarantees of legal certainty and stability of the voting system, guarantees that electoral commission members could conduct and monitor e-voting, guarantees and procedures for oversight of e-voting, guarantees of openness and publicity in drawing up lists of e-voting participants, guarantees that active suffrage rights would be observed in case of a failure of the e-voting system, guarantees of personal participation in e-voting, guarantees of the right to vote, guarantees of accountable vote counting and verification, and guarantees of a univocal interpretation of the law on the part of electoral commissions. In other words, nearly all major guarantees of electoral rights are missing from the format adopted for online voting. The expert criticism was simply ignored; no meaningful tools for ensuring transparency and oversight of electronic voting were added to the draft law.

The e-voting system will be a black box with a screen that shows some figures. However, members of the relevant electoral commission, let alone the public, will not be able to prove the validity of these figures. This system would be even worse than the Moscow system, which has been heavily criticised since its launch.

Reduced transparency of ‘regular’ voting

A number of amendments approved by the responsible Duma committee were added in the second reading. These amendments changed the original meaning of the draft law completely, as they had nothing to do with e-voting. First and foremost, they drastically reduce the number of non-voting members of electoral commissions.

Previously, in addition to candidates and voters, three other broad categories of individuals were involved in elections: voting members of electoral commissions (VMs), non-voting members of electoral commissions (NVMs) and observers.

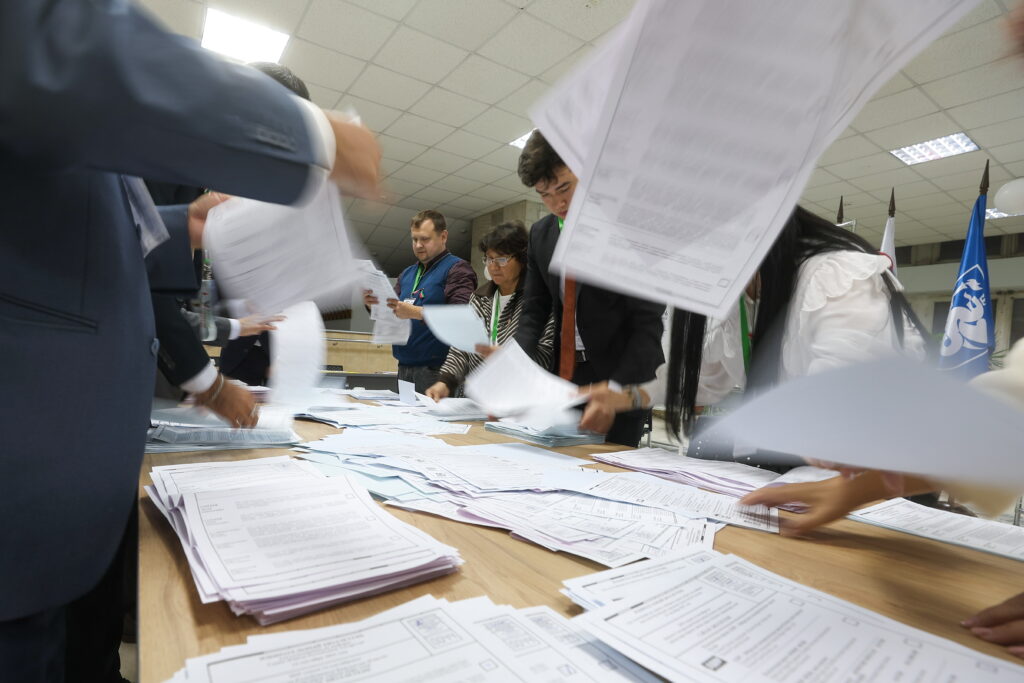

The former (VMs) conduct elections in the most outright way: they keep records, count votes and issue ballots. They are appointed for five years, and they tend to be extremely loyal or simply dependent on the government. Back in 2017, the Golos movement conducted a study of the composition of electoral commissions. It turned out that administrations at all levels play a major role in their formation, and United Russia’s representation and influence is disproportionately high. This is achieved in several simple ways. First, representatives of small parties, who in practice turn out to be representatives of administrative bodies, are included in electoral commissions. Second, members affiliated with United Russia (party officials or members, people who were nominated by the party in previous elections, etc.) join electoral commissions on behalf of public associations and voter assemblies. Third, representatives of administrative bodies and United Russia occupy senior positions on the commissions. As a result, the commissions are comprised of voting members, 80%-90%, and sometimes 100%, of whom are under the control of the authorities.

Observers are appointed by the associations and candidates taking part in elections. The problem is that this has to be done in advance, at least three days before voting day. In the case of major elections, it is almost never possible to have observers in every polling station, and anyone planning to commit electoral fraud knows in advance where they are going to be given a free hand and where it is better not to do anything illegal. It also gives the authorities an opportunity to put pressure on those observers who have already been appointed. However, the discretion of the observers is rather limited. For example, they have no access to documentation, and they can be observers only in the region where they legally reside.

Therefore, most candidates, parties and observer associations used to take advantage of their status as non-voting members, as they can be appointed at any time during an election and have access to documents, which means they have real control over much of the process. Currently, NVMs can operate only at the level of the Russia’s Central Electoral Commission (CEC) and regional electoral commissions. There will be no NVMs even on district commissions in single-member constituencies, which means that many candidates will have no full-fledged representatives even on the commissions that carry out registration of these candidates. We are talking about discharging hundreds of thousands of commission members, who will no longer be able to enjoy the most sought-after status.

Doing away with the institution of non-voting members was unpredictable. The result is that the accountability of elections to the public and to candidates will be greatly undermined. In addition, there are more possibilities to discharge observers and commission members not only from voting premises but also from the premises where voting protocols of a given constituency are submitted and compiled.

Other restrictions of citizens’ voting rights

The new law undermines the electoral law in other ways. For example, it extends the disenfranchisement period for those convicted on charges of extremism to five years from the date when their criminal record is cleared or the conviction expunged. Given the fact that Meta, which owns a number of social media outlets and a messenger application, is recognised as an extremist organisation, the problem could potentially affect millions of Russians. The authors of this initiative claim that recognition of Meta as an extremist organisation will not affect ordinary users, but the law as it currently stands does not provide any legal guarantee of this.

The procedure for postponing voting during a period of high alert or an emergency situation is also simplified. Voting can now be postponed even when there is no threat to the life or health of voters. In this regard, it is already being debated whether this year’s gubernatorial elections should be postponed or cancelled altogether.

The approved amendments propose a number of other changes, such as closing down municipal commissions.

All of this fits into the systematic restriction of the public’s right to observe elections that has been taking place over the past few years (and has been especially noticeable since 2018). During this time, there has been a ban on public video broadcasting, a crackdown on observer organisations (most recently the blocking of the Golos website on 11 March 2022), the fuelling of conflicts between commission members and observers, accreditation and seniority requirements for journalists to cover elections, prior registration for observers and now doing away with the status of non-voting commission members, which is the most valuable and most effective in terms of monitoring.

A separate issue is the impact of the blocking of almost all independent media outlets and foreign social media on the election debate.

Given the support of the Russian CEC (and often at its initiative), the authorities are increasingly diluting the institution of elections and modelling it after the Belarusian version, where one cannot even obtain information on precinct electoral commissions. This does not sit well with the allegedly increased popular support for the Russian authorities against the backdrop of the war. It rather demonstrates a lack of confidence that the autumn elections will be peaceful. At the same time, prior to the campaign against Ukraine, the Russian authorities were not expected to face any serious challenges in the autumn elections. There was some scheme only at the local level, such as the Vladivostok City Council election.

However, the elections will now be taking place during Russia’s ‘special operation’. Thus, a triumph under normal circumstances is clearly not expected.