In mid-May the State Duma unexpectedly adopted amendments to Russia’s electoral law. Most were not publicly debated; some were published on the official portal just one day before the third reading and the final vote.

The amendments can be broken down into several categories. The first consists of changes like a ban on candidates found guilty under any of 50 provisions of the Russia’s Penal Code. The second alters the rules of collecting signatures to nominate a candidate. The third category promotes forms of voting beyond solid public oversight. Namely: home voting, early voting, early voting at mobile polling stations, postal and electronic voting.

Why now? April and May are typical months for introducing amendments to the election law in Russia. They tend to be the eve of campaigns set to launch in June. Changes come almost every year. According to international democratic standards, election law should be stable.

So why these amendments this time? And how will they affect suffrage and the political system as a whole?’

Restrictions on candidates

Russian law already restricts nomination rules. For instance, Alexey Navalny could not stand in the presidential election.

The list of restrictions has been extended. Now, they include medium-severity offenses under any of 50 Penal Code provisions. These can be charges on political grounds. Extremism, for exampla, or separatism, dissemination of fake news, organisation of rallies, resisting arrest, etc. Or, candidates could be barred for economic offences, like various types of fraud, or drug-related crimes. Last summer’s examples of fabricated charges include police planting drugs on investigative journalist Ivan Golunov and citizens’ resistance to police at peaceful rallies.

Russians sentenced under these provisions (including suspended sentences) cannot stand for elections for eight years after completing their sentences. According to the Supreme Court, about 71,000 people were convicted under these provisions in 2019, meaning half a million people may be blocked from running for office. The majority will have been convicted of theft, but some will be political and civil activists, as well as entrepreneurs. Despite their political ambitions, they will not be able to run in the elections.

So, their supporters’ active suffrage will be infringed; access to the already closed shop will become even more restricted. Candidacies will not even be limited by election commissions, but by courts, which are held in low regard in Russia. According to VTsIOM (the Russian Public Opinion Research Centre), the courts have the lowest approval rating among all public institutions. Russians distrust them even more than the media, political parties and the opposition. The percentage of people dissatisfied with the courts is 12 points higher than the percentage satisfied with their work. The already critical attitude to the institution of elections will be further undermined by people’s distrust of court decisions preventing certain politicians from running in the elections.

Nominations will become more difficult

In line with what election experts claimed years ago, last year’s Moscow election showed it was practically impossible to nominate independent candidates based on collected signatures. It was not so much the required number of signatures. Moscow candidates, who had to collect 5,000-6,000 signatures, were refused registration. So were candidates from Irkutsk who gathered as few as 60-70.

Candidates were registered based on decisions by Interior Ministry experts who verified the validity and authenticity of signatures. These experts are fully dependent on the executive. Last year, a rejection of candidates resulted in mass rallies in Moscow which lasted a month. Interior Ministry officials disqualified authentic signatures of people ready to testify in court. Signatures were found invalid without justification, which made it hard to appeal.

Electoral experts suggested signatures could be collected via the Public Services Portal Gosuslugi, whose users have already been verified and authorised by the state. This should have solved the problem of the verifiers’ arbitrariness. The State Duma adopted amendments that allowed for the collection of up to 50% of signatures through the portal. Still, a plethora of caveats has destroyed the potential positive effect of this solution and complicated the situation of prospective candidates.

To begin with, this is only an option for regional parliaments to adopt provisions; the parliaments themselves set the limit on the share of signatures collected online. In practice, depending on the region, it can be as little as 10, 5 or 0 percent. At the same time, the maximum share of disqualified signatures was cut in half, from 10 to 5 percent. Moreover, voters will now have to add a signature and the date, as well as enter their surname, first name and patronymic. This will inevitably increase the number of errors. Additionally, the handwriting of the majority of citizens is far from calligraphic, allowing for misinterpretations by Interior Ministry officials. Besides, there is a change in the arrangements between the CEC and the Interior Ministry. Interior Ministry officials will no longer have to specify the nature of the errors they spot, making appeals harder.

For most would-be candidates, the only chance to stand for election will be nomination by a political party which is exempt from the signature collection requirement. Small parties and unaffiliated politicians will have to ally with larger groups. Or, indeed, with the authorities who control the Interior Ministry and election commissions. Independent actors can rarely be found among the ranks of the parties enjoying this privilege. Most of them coordinate their actions with the executive anyway.

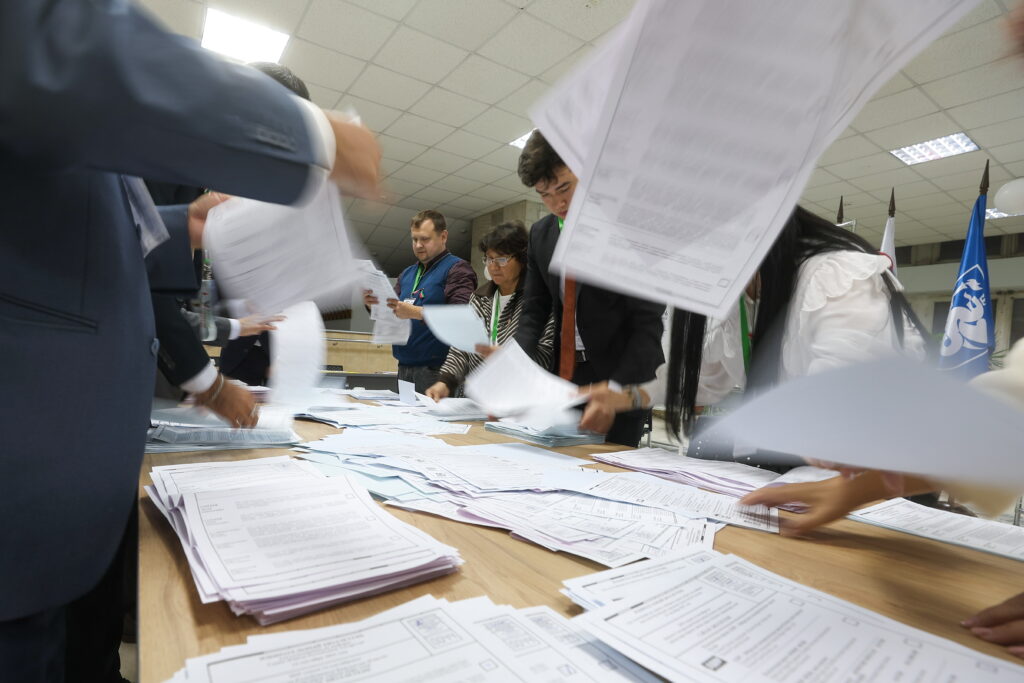

The voting system lacks transparency

The public was most shocked by the third subset of amendments, which extends the use of the forms of voting beyond public scrutiny. Against the backdrop of the coronavirus epidemic, the network of election commissions has been authorised to introduce remote (postal or online) voting on their territory. It remains unclear which commissions are vested with such powers and what the criteria are. All this will be spelled out in regulations of the CEC of Russia.

E-voting, used for the first time in Moscow last year, was heavily criticised. Besides technical issues, e-voting suffers from a cardinal sin: it is impossible to verify vote counts without undermining the notion of a secret ballot. It is either one or the other. And it is prone to voter coercion.

Voting by post did exist as an option in Russian election law but it was rare. The issues with postal voting are more or less the same: violation of ballot secrecy, susceptibility to vote-buying and coercion. Voting by post is considered a defective form of voting even in countries which apply it.

Early and home voting will be used on a larger scale. The outcome of voting using these methods differed greatly from the results of voting at regular polling stations on election day. Early and home voting have always come with coercion-related scandals and vote-buying.

Moreover, the mysterious method of early voting at mobile polling stations is now on the cards. Election commissions will be able to set up polling stations as early as seven days before election day. These polling stations can be located ‘in the surrounding area, public areas and other places’ for citizens who applied for home voting.

All these forms of voting be decisive in competitive elections or those with low turnout. The effect will be noticeable if all the measures are used at once. Imagine a regular local election with a 15-20% turnout. Now imagine that at least 1% of voters applies each of the alternative voting forms. As a result, up to one-third of all votes in such an election can come through forms which are almost beyond control of society, candidates or parties. In practice, their share in the ballot count may be even higher.

Unfair elections, but still elections

All the recent amendments reduce independent actors’ chances to appear in the political arena. They also create favourable conditions for even greater fraud and abuse of the so-called administrative resource. These changes are prompted by the electoral problems faced before by the authorities. These include failures in the 2018 and 2019 regional and local elections in Moscow as well as Zabaykalsky, Primorsky and Khabarovsk Krais, Khakassia, Vladimir Oblast and other regions. Domestic policy administrators realised they would be unable to achieve desired results relying on media control and administrative resource.

Most of these recipes were already tested in the recent past. The authorities decided to give them up as they attracted too much negative publicity and public discontent. Easier access to the political arena came in the aftermath of the 2011-2012 protests. These concessions were fraught with consequences: dozens of new parties emerged. Some managed to win elections at various levels. Early and home voting have been curtailed by the current CEC.

Following the amendments, these options will be promoted. The result is predictable: an increased number of electoral scandals and post-election protests. These will come alongisde a further decline of trust in electoral institutions.

At the same time, there are doubts that the authorities will achieve their desired results. Parliamentary parties will still be exempt from the obligation to collect signatures for their candidates. This is how independents may try to make it to the elections. That’s what happened in Moscow last year. Therefore, citizens will have an opportunity to express their will and their opinion of the situation in Russia. And sometimes they might stand a chance of electing a candidate of their choice.