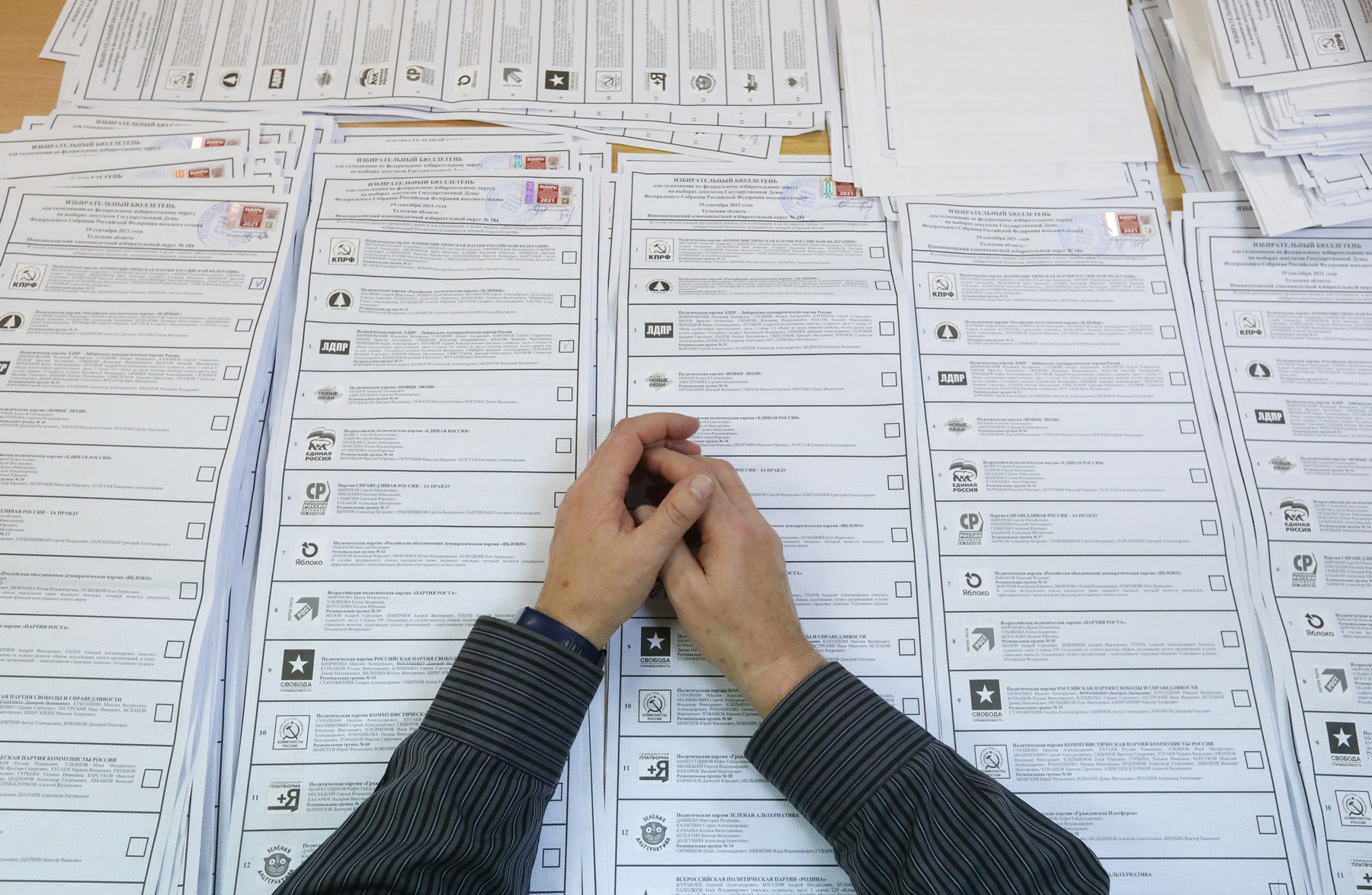

In 2021, a total of 4,876 election campaigns were held in Russia at different levels, from local to federal one. Most of them, i.e. 4,474, took place on the Single Voting Day on 19 September. The others, mostly small local elections, were held throughout the year, taking up 45 Sundays. The last elections during this year will be held on 26 December (in certain municipalities of three regions at once).

What has changed in Russia’s electoral and party systems over the year?

The changing party system

The 2021 change in the party system turned out to be quite significant. A new party, called ‘New People’, claiming to represent the interests of citizens with liberal views, made it to the federal parliament. The last time a similar party (‘Union of Right-Wing Forces’) made it to the State Duma was back in 2003. Not only did ‘New People’ pick up 5.6% of the vote (according to official data), but its members were also elected to 20 regional parliaments, which is an excellent outcome for a party that emerged merely a year before the elections, and had a rating of about 1% and low awareness at the start of the campaign.

For the time being, ‘New People’ remain a dark horse. On the one hand, the party had a clearly favourable regime for participation in elections: in 2020, the party was registered within an extremely short time, it was immediately allowed to take part in regional elections and obtain the right to nominate its candidates for the Russian State Duma elections without collecting signatures. We can at least say that ‘New People’ did not face any obstruction in 2021. Moreover, the party received a large amount of TV airtime on Russia’s Channel One and was actively present in the regional media and online social networks. The composition of the factions in the State Duma and the regions raises serious questions: most of the people there are unknown.

On the other hand, the party has already become noticed thanks to its initiative to revise the legislation on ‘foreign agents’. Even if we consider this a concerted initiative, the very inclusion of this proposal in the federal parliament’s agenda should be recognised as a positive development.

The emergence of ‘New People’ in the State Duma coincided with the fact that many supporters of Russia’s democratic development recognised the actual death of ‘Yabloko’, which, in fact, was already noticeable several years ago. Yabloko branches which were doing real work and had some electoral prospects have remained only in several regions. In essence, ‘Yabloko’ has turned into a regional party of North-Western Russia. Considering the emergence of the ‘New People’ in the Duma and the destruction of Alexei Navalny’s organisations, one can say that the ‘liberal’ flank in the Russian party system emerged as significantly renewed at the end of 2021.

There have been also some changes on the left flank.

This year, the Communist Party of the Russian Federation (CPRF) actually received a much higher share of the vote than reported by the Central Election Commission whereas ‘United Russia’ received significantly less than the official results. The Communists actually turned out to gather comparable level of support as ‘the party of power’, and even surpassed it in some regions. Worth noting is that the ‘Party of Pensioners’ also entered the local parliaments in 16 regions, and if it fails to fulfil its potential in the future, its voters represent the most immediate reserve pool of the CPRF and may return to the fold of the ‘big’ party.

The new status of the CPRF poses new challenges, i.e. the party must consider how to strengthen this position without disappointing voters and, at the same time, without putting the party at risk of being destroyed by force, as was the case with the structures set up by Alexei Navalny’s supporters. The serious pressure on the CPRF was already apparent during the election campaign (it was not only about Pavel Grudinin’s removal from the election but also about various regional cases). However, the increased risks for the Communists are even more evident in the post-election period: the special operation to capture Valery Rashkin with an elk carcass in the Volga forests, the rather absurd accusations against Artem Samsonov, a Primorski Krai MP, and the detention of Nikolai Bondarenko, a prominent deputy from Saratov. All this means that the serious shift that has been occurring in recent years has become more evident: the clear distinction between the ‘systemic’ and ‘non-systemic’ opposition has been blurred.

This boundary will shift increasingly towards the old ‘systemic’ politicians after the destruction of organisations of Navalny’s supporters, which, although not registered by the Russian Ministry of Justice as a party, actually resembled a party to a much greater extent than the absolute majority of registered political parties. This is another important consequence of 2021: as some ‘extremists’ get eliminated, those who previously were considered quite ‘systemic’ become new ‘extremists’. This is how the boundary of what is permissible in politics will shift further and further.

Restrictions on citizens’ voting rights

The year 2021 also saw a continued propensity towards restricting citizens’ electoral rights. Such restrictions are not new: the gradual displacement of representatives of large groups of citizens from public politics has been taking place since the mid-2000s, when active electoral rights were first banned for holders of a second citizenship, foreign residence permits or foreign assets. These groups include millions of the most ‘globalised’ Russians.

Throughout 2021, these restrictions were supplemented by a purely ‘political’ ban on voting, imposed on citizens who have been found to be involved in the activities of banned ‘extremist’ or ‘terrorist’ organisations. Moreover, the new legal provisions have been formulated in such a way that they cover actions committed three years before the law entered into force, and the definition of ‘involvement’ turned out to be so vague that almost anyone could meet the criteria. As a result, human rights defenders are talking about 9 million Russians who have been already deprived of passive suffrage, and an unlimited number of those who can be potentially deprived of it (Russia’s Central Election Commission claims that the number of ‘deprived citizens’ is much lower, but has been unable to provide any substantiation for its figures for six months now). After the adoption of the new law, a number of Navalny’s structures were recognised as ‘extremist’.

All this, together with other conditions to be met candidate registration, led to a decline in the number of people who are willing to run in elections. Many politicians with sufficient potential simply refrained from doing it. This is important because quite a large group of people still have political ambitions but, at the same time, they are aware that it is impossible for them to engage in politics legally.

However, it is not only passive suffrage that has fallen under restrictions this year. In fact, the developments have also affected active suffrage in a sense. The Constitutional Court of Russia considers the opportunity to verify the accuracy of vote counts as an integral part of the right to vote. However, unprecedented measures were taken in 2021 to prevent this right from being exercised: video surveillance was severely limited, completely uncontrollable remote electronic voting was introduced in several regions, and the Single Voting Day was extended over three days.

All this happened in parallel with pressure on civic observers and journalists. Moreover, efforts were made to make sure that obtaining official information from the websites of the CEC of Russia and other election commissions is highly difficult: the election organisers were simply trying to hide information about the flow and outcomes of the elections or to make such information difficult to process.

As a result, in the face of the growing rebellious moods, the Russian authorities are using all possible means to exclude citizens from the decision-making process and deprive them of sovereignty. This essentially ‘defensive’ position explains the repressive actions adopted by the authorities in recent months. However, this has clashed with another trend observed by social scientists: the Levada Center has recorded a significant increase in Russians’ demand for fundamental political rights and freedoms over the past four years: freedom of speech, freedom of movement, freedom of conscience, the right to participate in public and political life, and freedom of assembly are currently viewed by Russians as important 1.5 to 2 times more often than in 2017.

This means we can be sure at this final period of the year that the conflict between the authorities and a significant portion of the society will not disappear: it runs quite deep. As a consequence, the authorities will tighten the screws and intensify repressions (let us recall one of the earlier points made here: the boundaries of things that are allowed have shifted noticeably in the last couple of years). It is likely that the authorities will attempt to tighten control over media space, i.e. the remaining media outlets (as well as their speakers and newscasters) and, primarily, the Internet. It is the Internet and the social media that particularly clearly demonstrated the presence of two information realities in the country in 2021: the official TV-reality and a more free Internet reality.

At the same time, the Russian rhetoric about the need to put the IT giants under government control coincides with the rhetoric found in Western democracies, which is why it will be much more difficult to fend off the demands of Russian regulators. It seems that in order to prevent authoritarian regimes from speculating on this topic one would need to establish an external social media arbitrator to resolve disputes over content blocking: there could be a kind of ‘jury’ involving members of civil society organisations. Incidentally, this would also allow social media owners to shed some of the responsibility for content moderation.

The battle for freedom on the Internet is probably going to be one of the main events in Russian domestic politics over the coming years, also in the electoral realm.