Russian elites, including Vladimir Putin, and propagandists are energized by the negotiations between Russian and American delegations in Riyadh. The negotiators themselves—among them individuals personally close to Donald Trump and Vladimir Putin (Steve Witkoff and Kirill Dmitriev) as well as career diplomats—speak of positive impressions from the meeting. Public satisfaction has also been expressed by the leaders of Russia and the United States. It’s quite likely that Putin and Trump will soon meet in person, and Moscow’s hopes for this encounter are turbo-optimistic. For the Russian president, it’s flattering that his expulsion from major Western politics is coming to an end—at least for a while. Trump himself gives Kremlin further reason for optimism: he lashes out at Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky (a move eagerly amplified by Russian state media), calling him a «dictator» and criticizing his supposedly low approval ratings based on fabricated figures. Putin, meanwhile, escapes even a fraction of this criticism, and such behavior from the American president is clearly something that should satisfy him.

However, Russia and the U.S. have yet to reach any clear agreements; they are still sizing each other up, and it’s not guaranteed that each side’s proposals will suit the other. Trump acts unpredictably and inconsistently. For now, his tactic seems to be a diplomatic blitzkrieg—pressuring Ukraine, extracting something from Russia, and emerging as a victor in the eyes of the American public and other world leaders. If this quick-strike approach fails, Trump is likely to shrug and step aside, as he has done before. Within Russia’s power vertical, some understand these quirks of the American president. In 2016, propaganda got burned by misjudging him: initially portraying Donald Trump as almost an ally of Russia, they had to shift tones after he introduced new sanctions. Since Trump’s election, senior siloviki have urged against placing excessive hopes in him, while Kremlin experts have been tasked with «lowering expectations» among Russians regarding the American president’s actions.

These negotiations have clearly shifted this pragmatic stance. If Americans were previously depicted to Russian audiences as the primary enemies and culprits of all woes, they are now, if not friends, at least bearers of similar «traditional values» with whom business can be done. For a long time, the U.S. was cast as a treacherous aggressor intent on dismantling Russia and seizing its resources—a malign strategy countered by Vladimir Putin as the guardian of national sovereignty. Now, members of the Russian delegation are openly offering Washington the very resources it was supposedly plotting to take. Caught up in turbo-optimism, the elites and propaganda aren’t even attempting to ensure a smooth pivot toward Trump or to prepare a clear fallback if the talks falter. Political administrators are stoking the same turbo-optimism among Russians. Media outlets and popular Telegram channels are spreading rumors of Western companies returning: clothing brands, car manufacturers, McDonald’s, Starbucks, and even Visa and Mastercard payment systems. Russian officials—like Industry Minister Anton Alikhanov—have begun warning these «returning» brands about challenges, thereby legitimizing the rumors. Interestingly, just weeks ago, Russians were being convinced that Western brands were unnecessary, as the country had its own domestic alternatives. The companies themselves have already debunked claims of an imminent return; moreover, even Russian analysts concerned with their reputations explain that beloved brands won’t be back anytime soon—if ever—since investing in Russia has proven excessively risky, and the Russian market is relatively small. Yet, a war-weary segment of society, longing for a return to normalcy, will latch onto these rumors with hope—an understandable emotional response.

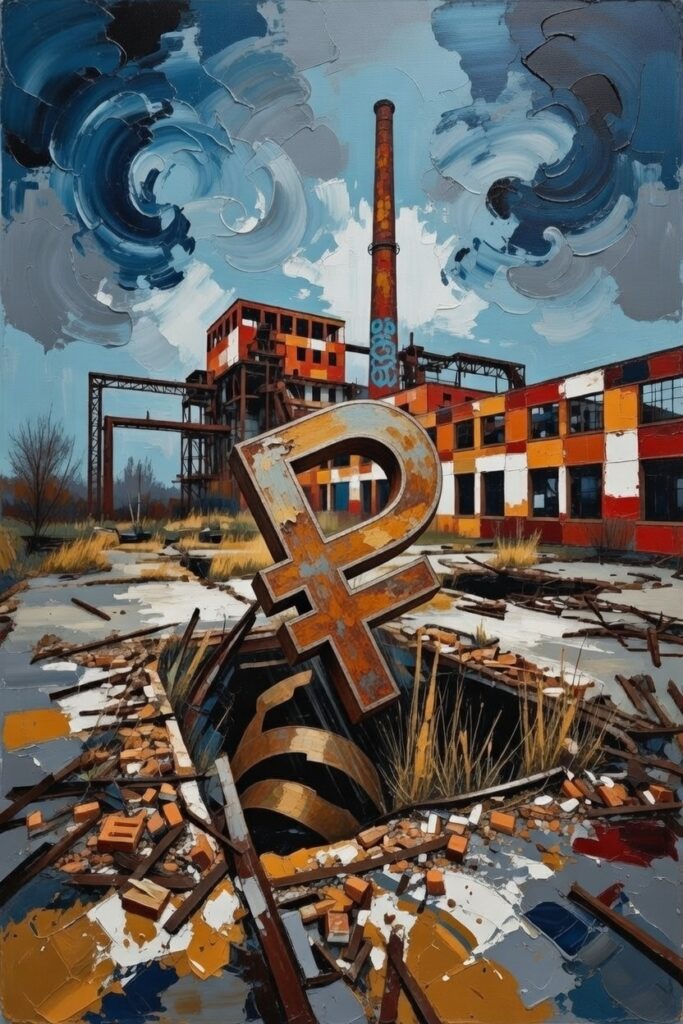

In the tactical short term—over the next few weeks—the Kremlin is indeed winning. We can expect a drop in public anxiety, which has long been off the charts, and a boost in approval ratings for the authorities, particularly Vladimir Putin. But in the foreseeable future, this imposed turbo-optimism could give way to harsh disillusionment. Trump is unlikely to prove a reliable ally. Even if the war ends, familiar brand stores won’t reopen overnight—and even if they did, prices reflecting the rising dollar and euro exchange rates would hardly delight Russians. The intoxication of anticipated success threatens to turn into a brutal hangover.

Divide and Conquer

The Central Election Commission has tallied the number of Russian voters, reporting a total of 111.56 million. Compared to last year, the Russian electorate has shrunk by half a million. Factoring in the annexation of parts of Ukrainian territory, the commission is preparing to redraw single-mandate districts for State Duma elections (225 in total) and has outlined the parameters for this redistribution. The annexed Donetsk and Luhansk «People’s Republics» will receive three and two districts, respectively, while the Kherson and Zaporizhzhia regions will each get one. Moscow, the Moscow Region, and Krasnodar Krai will gain districts. Meanwhile, ten regions will lose one district each, including potentially protest-prone areas like Altai Krai, Tomsk Oblast, and Zabaykalsky Krai. In Zabaykalsky and Altai Krai, there are Duma single-mandate deputies who won competitive races against United Russia candidates—Communist Maria Prusakova (Altai) and Fair Russia’s Yuri Grigoryev (Zabaykalsky). These politicians are popular in their districts, engage with constituents, and were poised to win again. Now, they’ll lose that opportunity. Tomsk Oblast has historically delivered protest votes in federal and regional elections and could do so again. Reducing the number of districts in the region makes it harder for systemic opposition candidates to win: campaigns become more expensive and require more meetings. Administrative candidates, however, find it easier to prevail, as the network of government offices and state institutions spans the region uniformly. Additional districts went to regions that consistently deliver record results for the authorities and are guaranteed to send United Russia deputies to the Duma.

Thus, the Central Election Commission has worked to address the problem of unsanctioned candidates—those not approved by the Kremlin’s political bloc—entering parliament. In the last elections, such figures included the aforementioned Prusakova and Grigoryev, Communist Oleg Mikhailov from the Komi Republic, and former Yaroslavl Oblast Governor Anatoly Lisitsyn, who ran with Fair Russia. Yakutian Communists also held onto their district. Now, the election prospects for many of these locally entrenched, unsanctioned candidates are significantly complicated. This redistricting is yet another sign that the Kremlin is determined to secure a new level of total dominance for United Russia in the State Duma.