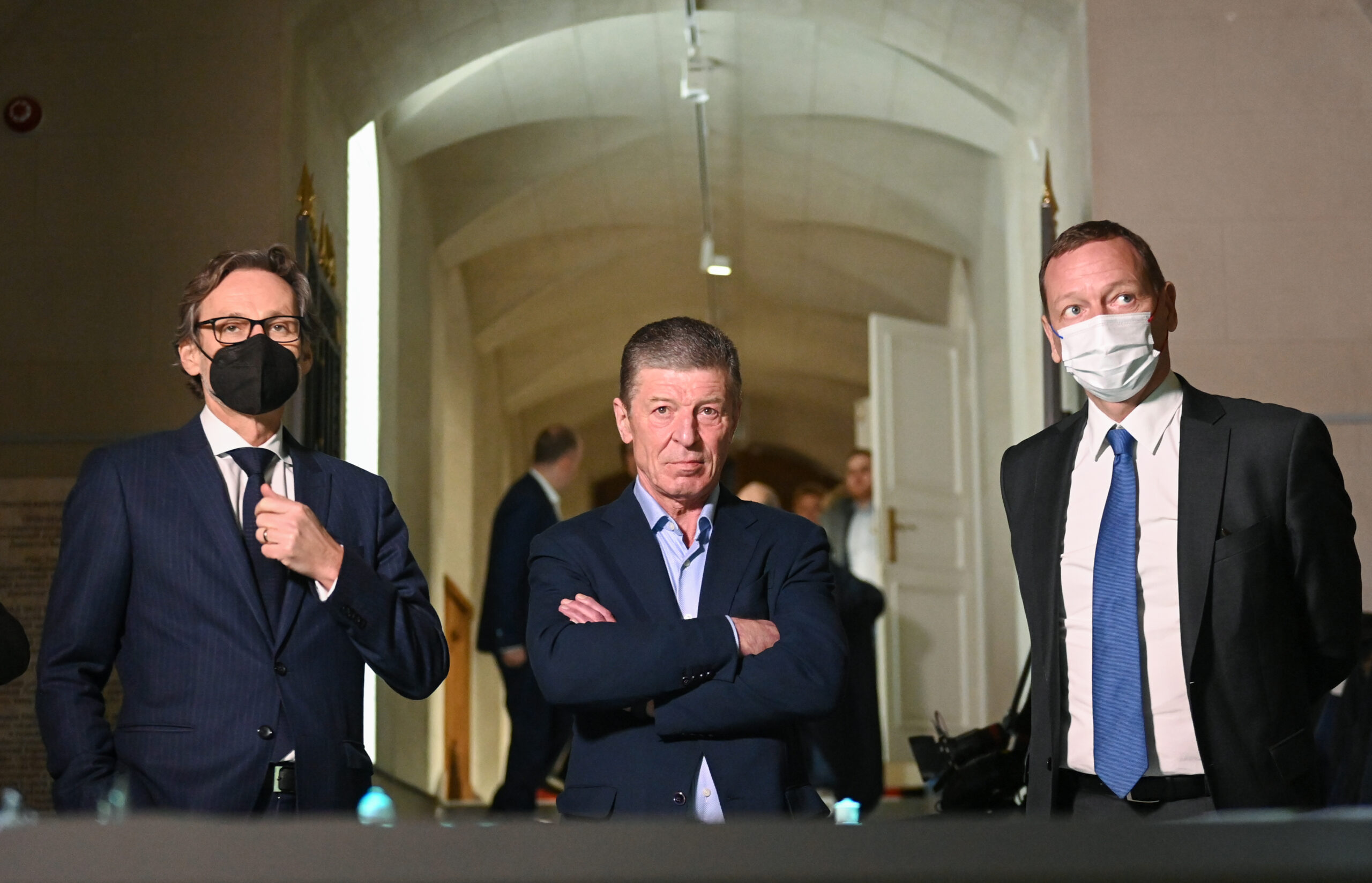

Deputy Head of the Presidential Administration Dmitry Kozak voluntarily left his post after losing all real powers in the Kremlin. He oversaw relations with post-Soviet countries, and before the start of the full-scale war — negotiations with Ukraine and the then non-annexed DPR and LPR. At the end of August, Vladimir Putin abolished the Presidential Administration departments for interregional and cultural ties with foreign countries and for cross-border cooperation, creating a single department for strategic partnerships in their place. The liquidated structures were subordinate to Kozak, while the new department will be controlled by the First Deputy Head of the Administration, curator of the Kremlin’s domestic political bloc, Sergei Kiriyenko.

Since the fall of 2024, Kiriyenko has begun an internal bureaucratic struggle against Dmitry Kozak, expanding his sphere of influence at the expense of the now former colleague’s powers. This struggle ended in Kiriyenko’s success, including due to renewed discussions of information that Kozak had fallen out of favor for opposing the war.

Kozak’s departure appears as an extraordinary event, but it was essentially predetermined back in the spring, when the ex-official began losing powers. The old Putin guard is giving way to more ambitious favorites ready to unquestioningly carry out the president’s will. Dmitry Kozak, who always had his own opinion and knew how to defend it, turned out to be an extra person in this servile «court 2.0.»

A Friend on Special Assignments

Dmitry Kozak is a comrade of Vladimir Putin from the time of their work in the St. Petersburg City Hall. Like the president, he studied at the law faculty of Leningrad State University, where the future mayor of Leningrad and then St. Petersburg, Anatoly Sobchak, taught. After coming to power, Sobchak invited some of his students to work in the city administration. Among them was Kozak, who by the end of the 1980s had already worked in the prosecutor’s office and in newly emerged private firms. In the mayor’s office, he headed the legal committee and earned a reputation as a professional lawyer. Kozak’s committee became one of the key subdivisions of the administration, and colleagues, including Vladimir Putin, head of the committee on external relations, turned to it for expertise on their initiatives. In 1999, becoming prime minister, Putin called Kozak to the post of head of the government apparatus, so their relationship could be called close and trusting.

In 2000, President Putin planned to appoint Kozak as Prosecutor General, but in the end left the post to the acting Vladimir Ustinov, not wanting to conflict with the prosecutorial corporation. Nevertheless, work was still found for Kozak: he became Deputy Head of the Presidential Administration, oversaw administrative and municipal reforms, and upon returning in 2004 to the post of head of the government apparatus, monitored the activities of government officials. In the position of envoy, Kozak also «brought order» to the Caucasus. From 2008 to 2020, as deputy prime minister, Kozak was responsible for important directions for Putin: first for infrastructure preparation for the Sochi Olympics, then for the integration of the annexed Crimea and Sevastopol, and later — for the fuel and energy complex.

In 2019, Kozak, known as a skilled negotiator, played a key role in forming the Moldovan government, preventing the Kremlin-hostile oligarch Vladimir Plahotniuc from coming to power. He organized a coalition of pro-Russian and pro-Western forces, although such negotiations were not formally part of his duties as deputy prime minister for the fuel and energy sector — Kozak acted as Putin’s trusted representative. In 2020, Kozak returned to the PA, where he began overseeing negotiations with Ukraine in the «Normandy format,» the so-called DPR and LPR, as well as relations with post-Soviet countries.

People began talking about Dmitry Kozak as a person particularly close to Vladimir Putin from the very beginning of the 2000s. He was tipped for the post of prime minister and even the position of presidential successor. However, when these expectations were not met, rumors arose about him losing influence. It’s hard to believe in Kozak’s succession: in 2007, Putin chose deputy prime minister Dmitry Medvedev as his successor, not Defense Minister Sergei Ivanov, because the latter would hardly have agreed to give up the post in 2012. Most likely, Kozak — a principled and strong-willed person — would also not have returned power to Putin. But past talks about Kozak losing influence were also hardly related to reality: Putin continued to entrust him with certain projects, appointing him to positions formally related to them. These positions could differ in their place in the official hierarchy, but the main thing for Kozak remained his informal status as Putin’s special envoy, his crisis manager.

Too Independent

In this status, Kozak could afford to express his own opinion and stick to his line if it contributed to the effective implementation of projects. At the same time, it should be noted that the ex-official did not take on deliberately unfeasible projects and always remained a realist. He was ready to listen to experts and delved deeply into the essence of the matter himself. These qualities were important for Putin. However, now the Russian president is bringing in quite different people — those who are ready to agree with any of his proposals, talk about successes, downplay problems, and organize large-scale events. Such figures include, for example, Sergei Kiriyenko and Deputy Head of the PA for the economy Maxim Oreshkin. Even government technocrats, such as Finance Minister Anton Siluanov or Central Bank Governor Elvira Nabiullina, have learned in public speeches to mask problems, using euphemisms like «economic slowdown» or «soft landing.» The sharp in judgments Kozak fit poorly into this company.

At the historic Security Council meeting on February 21, 2022, Kozak spoke not only against the full-scale invasion of Ukraine but also against the recognition of the so-called «people’s republics»: he pointed out that Russia was already spending «astronomical sums» on their maintenance. Before the start of the full-scale war, Kozak conducted negotiations guided by rational considerations: he was ready to support the return of Donbass to Ukraine in exchange for lifting sanctions from Russia. His realistic and rational approach allowed him to effectively solve tasks, but it was precisely this connection with reality that made him a stranger in the new political environment.

Of course, on February 21, Vladimir Putin did not listen to either Dmitry Kozak or Nikolai Patrushev, who, holding the post of Security Council Secretary at that time, advised continuing negotiations. However, if Patrushev after the start of the invasion became a staunch supporter of the hard line and an active war propagandist, Kozak preferred to step back into the shadows, focusing on the Kremlin’s policy in the post-Soviet space. He did not support the decision he had initially opposed. This became the extreme point of divergence between Kozak’s work style and Putin’s current expectations from his entourage. Today, it’s hard to imagine the Kremlin embarking on subtle political maneuvers like the coalition of pro-Russian and pro-Western forces in Moldova. Putin needs clear victories for his protégés, not the promotion of Russian «soft power.» Sergei Kiriyenko is ready to work in such a style.

The Old Guard is Losing Positions

Dmitry Kozak’s star began to finally fade after Sergei Kiriyenko took on the organization of the presidential elections in Abkhazia in 2024. In the unrecognized republic, which is de jure part of Georgia, a political crisis erupted: local elites and residents opposed an agreement with Russia that the Kremlin and the Russian government proposed for ratification by Abkhaz deputies. The document provided for broad benefits for Russian business. The discontent spilled over into protests that led to the resignation of President Aslan Bzhania.

In the subsequent elections, the Kremlin’s protégé Badra Gunba and former Finance Minister Adgur Ardzinba clashed. Both politicians were loyal to the Kremlin, but Kiriyenko bet on Gunba, who was relatively weak in public politics, and ensured his victory (likely with the help of falsifications). However, during the campaign in Abkhazia, internal conflicts intensified, and after the elections, society turned out to be divided. Kiriyenko delivered a short-term result to Putin, which in the long term may create problems for Russian policy in the region. Kozak, most likely, would have acted differently: he would not have suppressed the opposition, as even the «oppositional» Ardzinba would have cooperated with the Kremlin.

After this, Kiriyenko began gradually taking away from Kozak the oversight of individual countries and territories (Armenia, Moldovan Transnistria), probably offering Putin tougher and more straightforward solutions. The abolition of two PA departments and the creation of a new structure under Kiriyenko’s leadership formally sealed his bureaucratic victory. Putin was ready to offer Kozak a compensatory post as envoy in the Northwestern Federal District, but the longtime comrade refused this «handout.» This is not surprising: by his decision, the president essentially allowed Kiriyenko to publicly humiliate Kozak, portraying him as a weak figure in the bureaucratic struggle. By leaving of his own accord, Kozak made an effective move.

Many media outlets and commentators link his departure — voluntary or forced — precisely to his position on the war. However, in the same «court 2.0,» there are supporters of ending hostilities, for example, the head of the Russian Direct Investment Fund, Kirill Dmitriev, who is making efforts to organize negotiations between Putin and US President Donald Trump. But unlike Kozak, Dmitriev is ready to agree with any instructions from the president and even reshaped his public image to please him. At the same time, the dialogue between Putin and Trump has reached a dead end, including because the negotiation organizer is not ready to persuade the head of Russia but merely follows his instructions. This is the main difference between the representatives of «court 2.0» and the old guard of Putin’s envoys. Kozak left the field of bureaucratic battle with losses because he was not ready to abandon rationality and consideration of reality in his actions. The time for decisive and sufficiently independent Putin emissaries and commissars has long passed, and Dmitry Kozak, one of the first such commissars, became the last representative of this guard.