In its current form, the Russian register of «foreign agents» is often mistaken for a VIP list of Russian celebrities from the world of politics, cinema, pop-culture, stand-up comedy or music. However, this is a misleading impression: not only does this status entail significant obstacles and limitations for those in the register, but it has also been conceived of and is currently implemented as a repressive measure that enables the authoritarian state to exercise pressure on civil society.

Since the status of «foreign agent» entered Russian political and legal reality in 2012, Vladimir Putin has insisted that it is a literal copy of the American FARA (Foreign Agents Registration Act), adopted in the late 1930s. However, over the past ten years and through all its modifications and amendments, the Russian law has never come anywhere close to the FARA, which regulates the activities of lobbying structures in the United States. Instead, it has become an authoritarian practice, the benefits of which have been appreciated by other non-democratic regimes across the post-Soviet space, for instance, by the governments of Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan. In Georgia, an attempt was made to pass a similar «foreign agents» law, but the idea was dropped following massive protests and public pressure. In Belarus, the adoption of such a law was discussed in 2021, and in Kyrgyzstan such a law has now been passed at first reading.

Russian «foreign agency» exponent

The law, which the media almost immediately dubbed the Foreign Agents Act, was adopted in its first version in 2012 in the form of amendments to the Federal Law on Non-Profit Organisations. The amendments entered into force in 2013. This version of the law, which seems rather mild and restrained compared to today’s practices, concerned only officially registered non-profit organisations. The Ministry of Justice would include NGOs in the register of «foreign agents» in case they met two conditions: (1) they had to have in their account receipts (in the form of a grant or donation) of any amount from a foreign person or organisation; and (2) they had to be engaged in political activity. Predictably, the second point became the bone of contention: while financial income from a foreign entity was an ascertainable fact, political activity was a matter of interpretation for the Ministry of Justice, law enforcement agencies and the courts. Almost immediately, it became clear that the authorities understood political activity to mean a wide range of public activities typical of NGOs: round tables, presentations and public speeches. Those organizations that ended up on the list of «foreign agents» had to carry the burden of additional expenses: they were obliged to report on the finances and the content of their activities, mark all their publications, begin each oral statement with a disclosure that it is being given by a «foreign agent», revise their fundraising strategies and internal security rules, etc.

In the first stage of designating NGOs as «foreign agents», the targeted non-profits occasionally managed to fight back in court, but research shows that even this version of the law became a source of considerable stress for Russia’s «third sector».

For the NGOs, the main consequences of the law were as follows:

- difficulties procuring financial support for one’s activities: throughout the 1990s and 2000s, grants from international foundations were the key source of funding for professional Russian NGOs

- growing costs of expressing a particular public position on current issues as this could be interpreted as a form of «political activity»

- political divisions within the professional NGO community between those who accepted the rules of the game and decided to obey the law and those who took the path of defiance and non-acceptance (creating a new organisation, dissolving the existing NGO, continuing to work informally or ceasing to work altogether).

The period when grants from independent international donors were an important source of funding was finally over with the adoption of the 2015 «undesirable organisations» law, which effectively banned the activities of many foundations in Russia (Soros Foundation, USAID, NED, etc.). The large international foundations that were not affected by the ban soon decided to suspend their activities in the country (MacArthur Foundation, Mott Foundation, MATRA programme, etc.). Yet, in addition to the stick, the Russian autocracy began to use the carrot more actively in its attempts to undermine the country’s civil society: between 2011 and the early 2020s, state funding of NGOs through «presidential grants» alone increased more than tenfold, reaching a peak of 11 billion roubles in 2020. In the 2010s, «presidential grants» to NGOs, combined with other state funding (subsidies from the Ministry of Economic Development, the Ministry of Health, the Ministry of Education, etc.) or corporate funding (Timchenko Foundation, Lukoil, SIBUR programmes, etc.), completely replaced funding from international foundations and expanded the number of NGOs receiving funding for their projects.

In 2020, the definition of «foreign agent» was expanded: the Ministry of Justice was now authorised to designate as «foreign agents» not only officially registered NGOs, but also informal associations that were not legal entities, as well as media and ordinary individuals. The updated version of «foreign agent» automatically affected a wide range of citizens and organisations and became a source of problems for many journalists, activists, human rights defenders and bloggers.

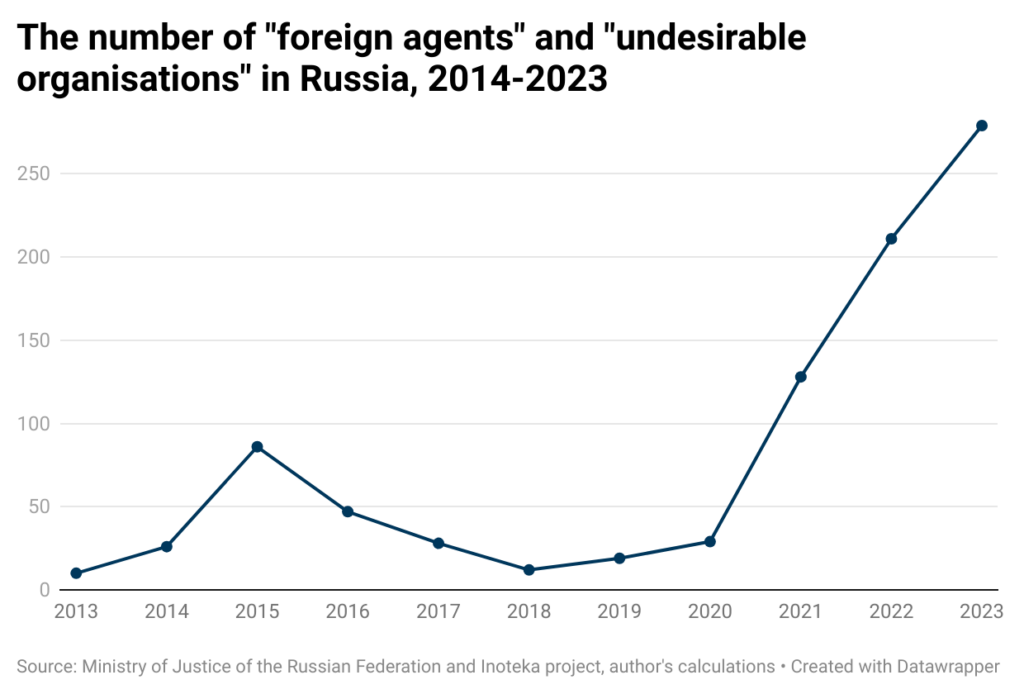

And yet the process of [weekly] registering NGOs and private citizens as «foreign agents» became a conveyor belt-like procedure only with the beginning of a full-scale invasion of Ukraine (in 2021 the regime designated 128 «foreign agents», in 2022 there were another 211 new ones, and in 2023 it added 262 organizations and people to the list). In the current political context, the «foreign agent» status has become a «Black Spot» in any civil-political relations with the state and a de facto ban on public activity. The new development that has been underway in the last six months or so — The Ministry of Justice and Roskomnadzor are actively preparing the legal basis that would enable them to initiate criminal proceedings under the «foreign agency» articles. Government agencies have begun to record «repeated violations» in the activities of «foreign agents» (lack of required labelling or irregularities in reports) on a mass scale, and to subsequently prosecute individuals and organisations.

Within ten years, the «foreign agent» status, while remaining a direct repressive practice against civil society, was transformed from a specialised tool of organisational pressure on a narrow circle of professional human rights NGOs into a tool of large-scale persecution and repression.

Exporting and importing authoritarian practices

Russia was not the first country in the post-Soviet space to control the activities of NGOs and their funding in order to curb their activities. In Tajikistan, a law was passed in the late 2000s severely restricting the funding of NGOs by foreign foundations. Significant restrictions against NGOs and activists have been introduced in Uzbekistan, Belarus, Turkmenistan and Azerbaijan. However, in terms of a special status for civil society representatives that restricts their activities, it is the Russian experience that has been exported over time to other autocracies in the region.

Kazakhstan tightened its legislation regulating activities of non-profit organisations in 2018−2020. It was then that the government created a «register of persons who receive money and (or) other property from foreign states, international and foreign organisations, foreigners, stateless persons.» The specificity of the Kazakh case lies in its public ambivalence. On the one hand, the Kazakh register is actually an analogue of the Russian one: both organisations and individuals can be included in it, and the status itself imposes an additional obligation to report to the state. Inclusion in the register mainly affects publicly active organisations and citizens, i.e. it is a kind of punishment for independent activity funded through foreign sources. On the other hand, the status of «foreign agent» has not been directly introduced in Kazakhstan; there is no mention of such a status in the law or in the register, which does not prevent the media from referring to this list of organisations and individuals as the «Register of Foreign Agents.»

In general, the diffusion of practices of political control and pressure on society is not an unusual phenomenon for authoritarian regimes. As political scientist Roman-Gabriel Olar has shown, drawing on the examples of autocracies in the Middle East and Latin America, autocracies are able to increase the effectiveness of repression by adjusting its degree and scale based on the mistakes of other authoritarian regimes. Autocracies imitate regimes with which they share similar institutions in terms of their repressive arsenal. Moreover, economically successful autocracies are welcome donors of repressive practices to authoritarian regimes from different regions. One of the most common practices of authoritarian control of civil society is the restriction or outright prohibition of foreign funding of non-profit activities. Suparna Chaudhry has estimated that between 1990 and 2013, more than 130 states, including democracies, erected barriers of varying degrees of difficulty to prevent NGOs from receiving foreign funding. Chaudhry also showed that autocracies tend to restrict civil society organizations from working specifically on political issues, drawing a line between loyal or acceptable independent activism and that which is unacceptable to the regime.

The cases of Russia and Kazakhstan look very typical and therefore indicative for understanding how organizational repression of civil society develops in an authoritarian context. Here we observe the diffusion of specific repressive practices, primarily the status of «foreign agent» itself. At the same time, it is important to note important variations and differences in the implementation and application of these practices in the two post-Soviet autocracies.

«Foreign Agents» in Russia and Kazakhstan

Apart from the fact that there is no explicitly designated status of a «foreign agent» in Kazakhstan, the Kazakh case also differs from the Russian one in that the register of unnamed «foreign agents» in Kazakhstan has existed as a public document for only half a year or som while the Russian regime has been busy designating individuals and legal entities as «foreign agents» for the past decade. In my analysis of both registers, I do not focus so much on the number of designated «foreign agents», but rather try to show what these repressive practices against civil society organisations and activists mean in the context of the Russian and Kazakh authoritarian regimes. By the end of 2023, there were 875 entries in the Russian register of «foreign agents». The dynamics of conferring the status of «foreign agent» or «undesirable organization» directly reflects the exponential growth in the repressiveness of the Russian autocracy. This dynamics also illustrates how the «foreign agent» practice has been transformed from an exclusive one, targeting a narrow circle of professional NGOs, to a much broader one, affecting independent activities of any kind.

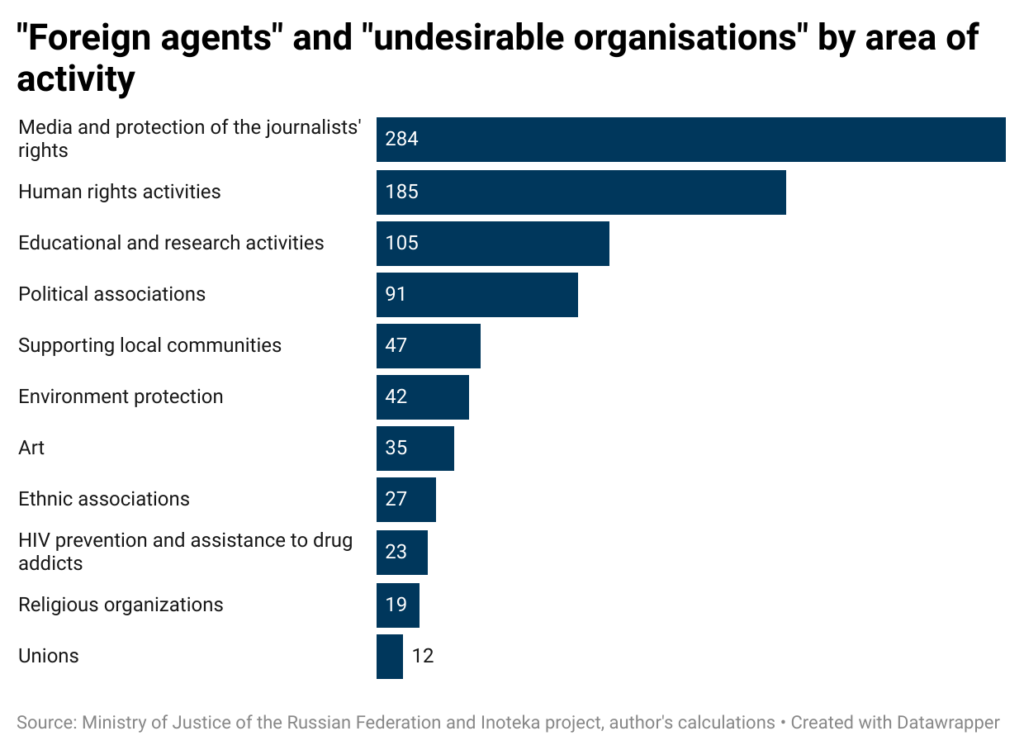

The breakdown of «foreign agents» by type of activity is noteworthy because it reflects the regime’s «ranking» of areas of civic activity that it considers undesirable. Thus, media (publications, TV and Youtube channels, bloggers) and organisations defending journalists’ rights constitute a solid majority, with around 35% of entries in the register. Human rights organisations and projects (including protection of women’s rights, protection of electoral rights, support for LGBTQ+ people, support for NGOs, etc.) account for around 22% of the register. Organisations and projects for awareness raising, education and expertise account for a significant share (11%). Political associations and individual public figures account for only 10% of the register. Other types of activities account for 5% or less.

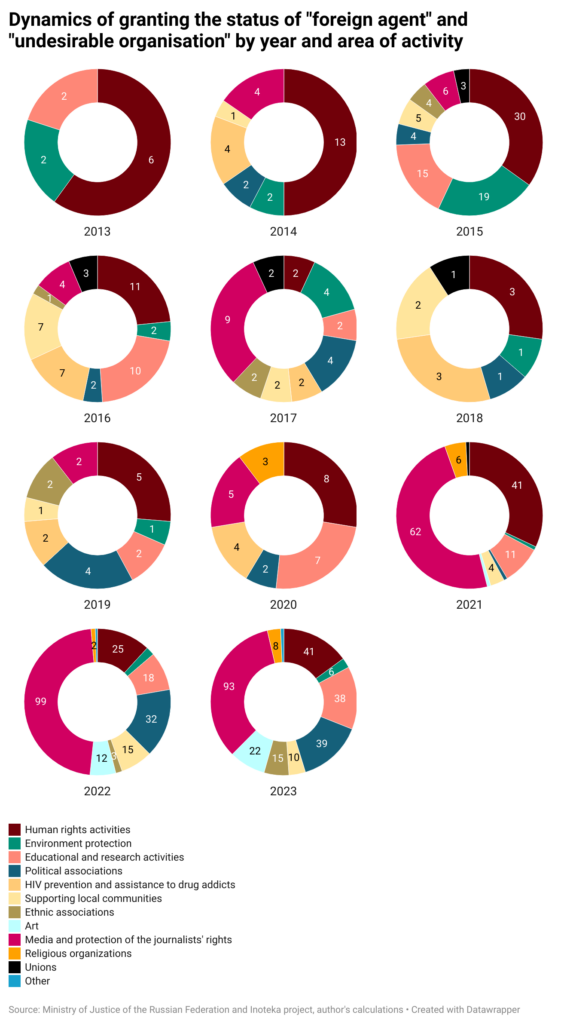

An analysis of the dynamics of the designation of «foreign agents» and «undesirable organisations», broken down by year and by area of activity, clearly shows that human rights organisations, projects and activists have been (and continue to be) the main targets of this repressive practice throughout the period. With few exceptions, it is human rights activity that has been blacklisted more often than other forms of activities over the past decade. We can also observe that throughout the period between 2021 and 2023 another group stands out: the media. The fight against independent media has been an important feature of Russian [domestic] policy in the context of the war against Ukraine. At the same time, it is noteworthy that the majority of media outlets received their repressive «foreign agents» status in 2021, i.e. before the onset of the full-scale invasion, which was probably one of the forms of political preparation for military aggression.

Finally, the analysis of these data demonstrates that the designation as «foreign agent» is an authoritarian political practice directed specifically against civil society and not against the regime’s political opponents. For the latter, the Russian autocracy had emooyed and is currently employing more severe repressive methods, while for civil society activists, independent researchers, experts, journalists, bloggers and human rights defenders, the regime has reserved the practice of sending a «Black Spot.» The practice of «foreign agency» that targets civil society looks like a relatively subtle, flexible and effective tool in the Russian context. On the one hand, until the radicalisation of the regime in 2021−2022, this practice made it possible to selectively single out certain organisations and activists or areas of activity and to apply state pressure on them in a targeted, «customized» manner. This sent clear and understandable signals about what public behaviour was considered (un)permissible. On the other hand, when such a need arose, the practice of designating individuals and legal entities as «foreign agents» made it possible to quickly and inexpensively redouble the state’s pressure on civil society and force a wide range of organisations and individuals to behave in a loyal manner.

Kazakhstan’s register of so-called «foreign agents» was publicly presented on the website of the Ministry of Finance in September 2023. It is important to clarify that the register of organisations and individuals receiving funds from foreign sources was published last year, but the Ministry of Finance of Kazakhstan has maintained this register since 2020−2021. Thus, the publication of the register should be seen as a political act on the part of the Kazakh autocracy, demonstrating its eagerness to actually implement a special status for organisations and individuals receiving foreign funding.

The register in Kazakhstan contains 239 names. A key feature of the Kazakh register is that it includes not only non-profit organisations or activists, but also simply commercial enterprises and businesses of various organisational forms. At a first glance, this makes the Kazakh register markedly different from the Russian analogue and even more similar to the above-mentioned American FARA. At the same time, as shown below, business entities make up the majority of the register: 109 entries, almost 46 per cent of the total list. Among the commercial entities included in the register are small and medium-sized enterprises that have contracts with foreign counterparties («Real Estate of Northern Kazakhstan» or the SIGNUM law firm), as well as representative offices of foreign corporations (e.g. representative offices of Mitsubishi Corporation, Gedeon Richter OJSC, Gazprom Bank).

Another peculiarity of the Kazakh register is that it includes so-called GONGOs, i.e. organisations directly created or controlled by the state. I am referring to regional branches (operating in Mangistau and Pavlodar regions) of the all-republican organisation Civil Alliance, which were included in the register because they had received grants from foreign foundations. According to media and experts, the Civil Alliance is Kazakhstan’s largest NGO, with branches in every region. It is an influential pro-government structure that often wins government contracts to provide social services.

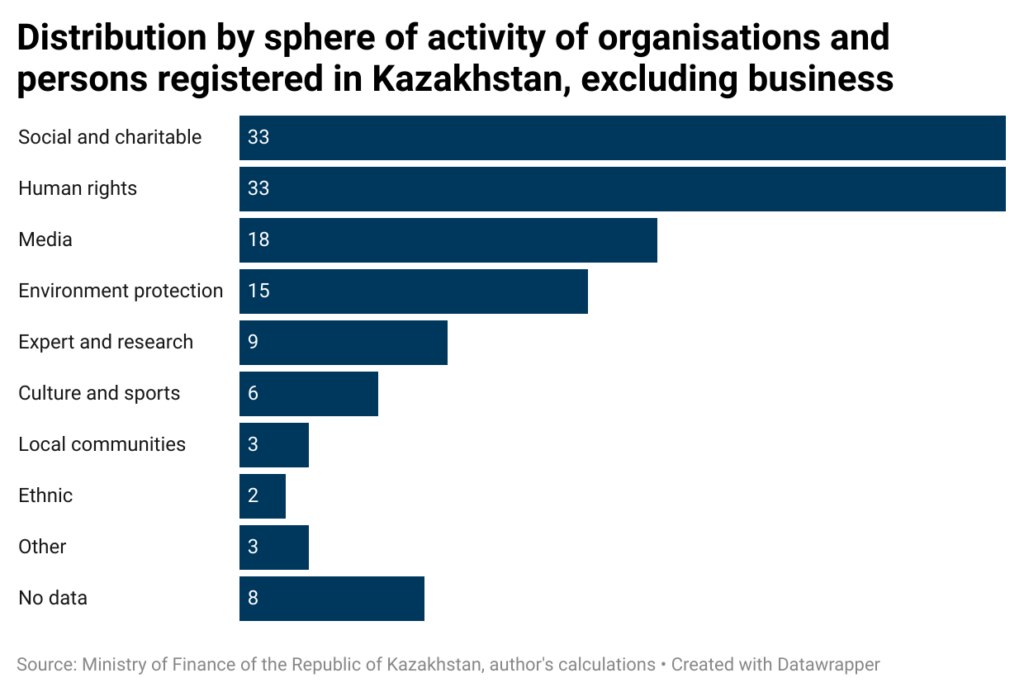

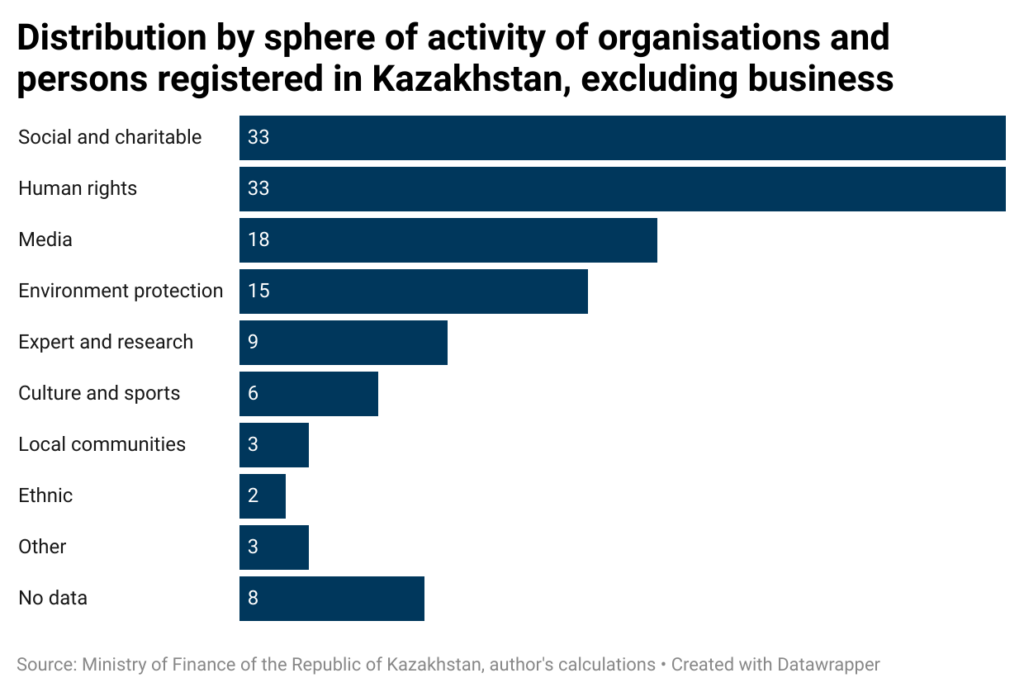

The inclusion of GONGOs and businesses in the register is a way of diverting attention from where the Kazakh authorities’ organisational pressure is really directed. If we bracket business from the register for a second and look at it again, we see that the main areas of activity of the organisations included in the register are human rights (25%), charity (25%), media (around 14%) and environmental protection (just over 11%).

Being included into the register in Kazakhstan, as in Russia, means additional organisational costs. Obviously, commercial structures with a large professional staff may not even notice this additional burden, but for non-profit and public organisations the costs might prove quite tangible. However, the biggest trouble is that in addition to the organisational routine (although there is not separate concept of a «foreign agent» and no legal obligation to mark all produced content, as exist in Russia) the register essentially introduces a special status for civil society organisations and draws a line separating certain organisations, activists and mediaf from all the others.

The case of Kazakhstan looks like an attempt to adapt the Russian practice of labelling organisations and individuals as «foreign agents.» On the one hand, the authoritarian regime in Kazakhstan achieves the desired goals by introducing additional control over the structures of civil society and outlining the boundaries of what is regarded as loyal, acceptable behaviour, venturing beyond which can be dangerous. On the other hand, by introducing the register, but not the «foreign agent» status itself, the regime minimises political costs and reduces potential public backlash against the introduction of new repressive practices.

«Give them your little finger, and they’ll take the whole hand»

CSO representatives and experts in Kazakhstan and beyond justifiably fear that the register has every chance of laying the foundaitons for systemic restrictions and repression of civil society. Its immediate function is to impose restrictions on institutional grants from international foundations operating in the country and funding non-profit projects. At the same time, this is a key source of funding for a significant proportion of charities and human rights organisations. Thus, as in the Russian case, this new policy can become a challenge for the entire community of professional NGOs and a source of organisational problems.

CSOs, activists and media in Kazakhstan and Russia have every reason to fear that the exponential expansion of the repressive power of the «foreign agent» status will continue. At the same time, such an expansion is possible both in terms of scale (it will affect more entities) and in terms of force: in the case of Kazakhstan it is possible due to the expansion of restrictions on those on the register, in the case of Russia due to the criminalisation of the status itself. Even if there is no expansion of repression, professional NGOs, media and activists in both states are currently facing difficult decisions about their strategies going forward.