Participation in space exploration not only contributes to Russia’s scientific, technological and industrial development but also plays an important political role. Surveys conducted by the Levada Center in 2011 and 2016, as well as a 2021 VCIOM poll, show that Russian society has long perceived astronautics as relevant and important. In fact, space exploration is one of the two reference points in recent history (along with victory in the Second World War) that enjoys a broad consensus among Russians and defines many features of Russian political culture. And it is this consensus that was exploited from the early 1960s by the Soviet authorities and that has been exploited by the Russian authorities since the early 1990s to ensure the legitimacy of the distribution of power and wealth within the country and of Russian decision-makers’ actions in the international arena.

In addition, astronautics has been the main symbol of authoritarian modernisation for decades. At the same time, successes and failures in the space industry are perceived by society as an indicator of whether the political and economic structure of modern Russia is right or wrong. This broad context should be taken into account prior to any transformations in Russian astronautics.

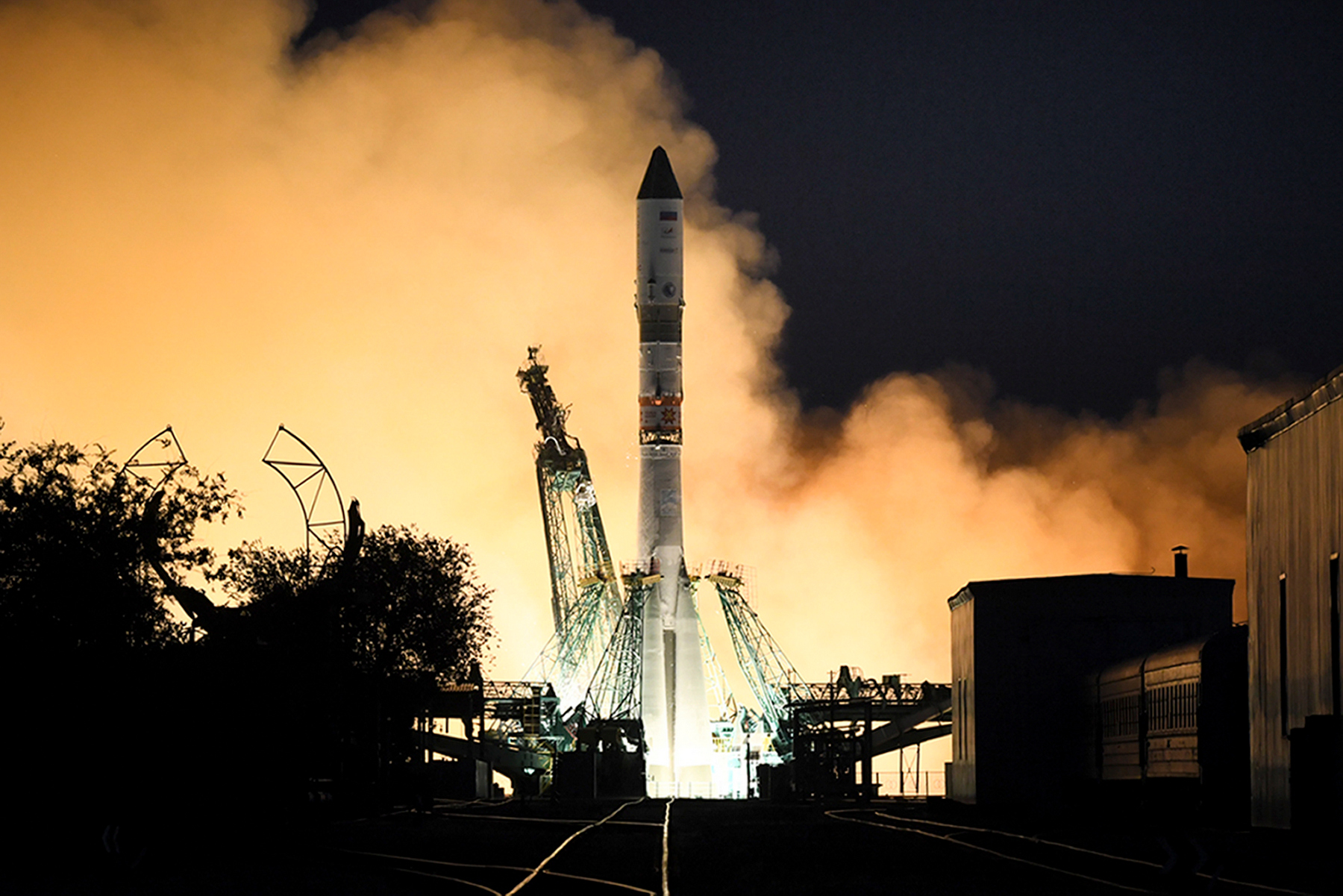

Russia’s priorities in space: overstretch

The objectives, principles and organisational foundations of Russia’s space industry are defined by a special law adopted in August 1993, even before the adoption of the Constitution. While the provisions of this law on the organisation of Russian astronautics have been repeatedly changed and amended since then, the goals and principles have remained the same. They will also be relevant in the future regardless of the political circumstances.

These include promoting the country’s economic growth and well-being of its citizens; developing scientific, technological and intellectual potential; accumulating fundamental scientific knowledge; promoting peace and international security as well as the security of Russia itself; developing international cooperation in space; etc. In other words, for nearly three decades we have had a clear and adequate system of coordinates to formulate what Russia should do in space.

However, in addition to the law, there is a document that outlines the specific priorities of Russian astronautics. This is ‘The Fundamentals of State Policy in the Field of Space-Related Activities’, adopted in January 2014 for the period until 2030. Although the document was unexpectedly amended in 2020 without being published, the basis of Russian space policy has not undergone significant changes. The main problem with this document is a set of provisions that exceeds the country’s objective capabilities.

Russian citizens bear the costs not only of financing the Russian government’s attempts to ensure Russia’s global space leadership, as well as its state-run scientific and defence space programmes, but also of developing the domestic market for space goods and services and expanding Russia’s share in the global market, which should actually be handled by commercial companies. Moreover, even before the annexation of Crimea, subsequent sanctions and launch of an import substitution policy, the task was set of ensuring the independence of Russian astronautics in basic space technology, which means, in fact, its decoupling from the international division of labour (industrial cooperation). However, this task had started to take shape even earlier, albeit in more moderate terms and within the catching-up development paradigm, which in itself was a much better reflection of reality.

The refusal to modernise economic and political institutions, which could be observed in 2012 and became salient in 2014, meant a course towards self-isolation. At the same time, the Russian authorities are aware of the need for technological modernisation and are trying to implement it in line with this approach, which has generated irreconcilable contradictions. While in the early 2010s a series of crashes of rockets and spacecraft indicated a crisis in the state industry, which was mitigated (but not overcome, as discussed below) by the government’s repayment of the debts of private enterprises, by the early 2020s the programmes themselves had reached a deadlock.

First, this is evidenced by the delay in the publication of Russia’s state programme of space activities for 2021–2030, apart from the undecided fate of the fundamentals of state space policy. To be more precise, given the circumstances, the 2013–2020 programme was simply extended to 2030. Second, there is a new, still unpublished version of the strategy of the Roscosmos state corporation until 2025 and for the period until 2030 (the original version was adopted in 2017). Third, there is no absolute clarity about the GLONASS satellite navigation system development programme for 2021–2030. The previous 2012–2020 programme expired but was never fully implemented. Thus, the books for Russia’s space activities don’t balance (see the tables below); a dramatic increase in expenditure is needed. At the same time, the space industry is suffering from the devaluation of the rouble, as well as Russia’s economic depression and ongoing confrontation with the West.

Roscosmos: crisis averted

The Roscosmos State Corporation replaced the Federal Space Agency in 2015 and combined the functions of the ordering party, contractor and regulator of space activities. It comprises 75 manufacturing and auxiliary enterprises that employ around 170,000 people. In addition to civil and military space programmes, the corporation is involved in the production of strategic and short-range tactical missiles.

Roscosmos was established to solve the following problems: the huge continuing losses in state astronautics, the increased failure rates in the early 2010s, and years of delays in the development and manufacturing of new space vehicles as well as the implementation of space programmes. It was an attempt to revitalise the industry within the existing institutional reality in Russia.

Roscosmos has been covered by the bailout programme: with the help of the government, the corporation has managed the most acute problems, such as high failure rates and the indebtedness of its enterprises. At the same time, it is launching a system of SPVs: a rocket engine manufacturer was established at NPO Energomash, and a space instrumentation holding company is being created at RKS. Holding companies manufacturing rockets and satellites as well as a space scientific company are about to emerge.

However, even a sustainable catching-up model is a challenging task for Roscosmos under the current economic and political circumstances. A dramatic increase in Russia’s spending on space-related activities beyond the limits outlined seems unlikely, and the lack of technologies (especially in space electronics) and human resources as well as the limited capacity of the Russian market are perceived as insurmountable difficulties.

Overall, there are three areas of Roscosmos’s activities that were predetermined back in the 1990s and that will be implemented regardless of political and economic developments in the country. First, the large-scale manufacturing of the Angara space-launch vehicles is planned. These rockets are based on the RD-191 engine, derived from the most advanced Soviet rocket engine, the RD-170. The same family of engines includes the RD-180 (used to power the American Atlas V rocket), the RD-181 (used to power the American Antares rocket) and the RD-171 MV, which is currently under construction.

Second, there is the upgrade of the crewed flight programme to a new technological level beyond the Soviet legacy of the 1960s and 1970s: the new crewed Oryol spacecraft and new crewed space modules based on the science and energy module (originally designed for the Russian segment of the ISS) that has been under construction for many years. Thus, Russia has little choice: it can either continue using obsolete Soviet technologies and abandon crewed space flights (with negative political consequences) or continue its efforts in the above direction.

Thirdly, there is the Vostochny Cosmodrome. Despite all its disadvantages (high costs and long distance both from the sea and from the country’s industrial centres), abandoning this spaceport after nearly three decades of design and construction works is hardly possible both for economic and for political reasons. Money has been spent; Russian astronautics is organisationally moving to this site. In addition, Russia simply cannot build a spaceport elsewhere, and the potential demoralising effect of such a move cannot be underestimated.

Still, Russian space-related activities can be brought in line with the country’s main goals and real capabilities, and Roscosmos can become a cost-effective company contributing to Russia’s development.

A fresh start

It should be said that Russia should give up trying to emulate the United States in the space sector. In addition, large private space companies will not be able to emerge in Russia in the foreseeable future, even under the most favourable institutional conditions. Not only is there no sufficient market for specialists and a capacious domestic demand for space services, but there is also no large private capital that could be invested in space.

The following is a realistic development programme for the Russian space industry:

- Roscosmos must continue to exist as a state corporation: transforming it back into a government space agency would require organisational efforts without any serious positive effect. After all, representatives of the government and presidential administration are already members of the corporation’s supervisory board. However, the activities of Roscosmos and its enterprises must become as transparent as possible, including through the mechanism of public parliamentary oversight. At the same time, the recurrent idea that Roscosmos could be divided into competing companies should be treated as outdated; a system of SPVs precludes such a division.

- The crewed programme should be implemented exclusively within the framework of international partnerships, primarily with the West, including industrial partnerships. At the same time, there is no critical need for the direct and/or permanent presence of Russian cosmonauts outside Earth after the ISS’s mission is completed (just as there is no pressing need in the case of China, Japan or the EU). The main thing is Russia’s input (in the form of crewed spacecraft and modules) to joint projects and the sustainability of partnerships.

- In general, Russia can and should abandon the idea of ‘space autarchy’; it needs to participate in the system of international industrial cooperation and restore legal access to foreign space electronics, which will obviously require the resolution of the current confrontation with the West and a thorough revision of Russian foreign policy.

- The priority of the civilian space programme should be independent and collaborative research in line with the goal of long-term scientific, technological and economic development of the country. Of course, this should be based on an economically efficient industrial base, manufacturers of equipment, rockets, etc., and on an open scientific and educational system.

- To encourage private initiative in the space sector, the approach of Japan and India should be followed. It is based on a grant system for space start-ups. In addition, private design engineers (including university teams) have access to public scientific and industrial infrastructure and are pursuing the long-term goal of integrating themselves into the global space market.

- At the same time, the Russian space industry as a whole must be freed from excessive regulation, especially by the security forces, as well as from the latter’s excessive influence on astronautics.

- Roscosmos can and should stop spending money on commercial space services such as television broadcasting, civil communications (including government communications), etc. These services could be offered by existing private Russian companies in the telecommunications and IT sectors, which could purchase satellites from foreign and Russian manufacturers based on the real needs of the market. Also, private Russian IT and telecom companies could serve the needs of military communications, reducing the costs of the defence space programme, which amount to several tens of billions of roubles per year.

- In the field of satellite navigation, the GLONASS programme should be revised towards reducing its cost. This is already happening now: the system’s architecture is being changed so that coverage of Russia’s territory would be provided not by 18 satellites in medium orbits (global coverage requires at least 24 satellites) but by six satellites in highly elliptical orbits. As a result, the system will be less costly for Russian consumers and will be able to function without a global option. At the same time, there is a possibility of interfacing such a system with the Japanese and Indian regional highly elliptical systems and the Chinese global navigation system, not only with the American GPS and European Galileo systems.

The efficiency of Russian astronautics can increase dramatically without raising costs and without breaking or radically redesigning the existing space industry; it is enough to align priorities and not try to do everything at once. This will also produce a positive political result: Russia’s place in the club of leading space powers will be secured by partnerships and its own research ambitions.

*This article is part of the ‘Reforms’ series prepared by Riddle in partnership with Reforum project.