Regional and local elections went almost unnoticed against the backdrop of the election to the Russian State Duma. At the same time, new legislatures were elected in 39 regions, where almost half (45.5%) of the country’s voters reside. Regional and local elections are major processes that are often less visible when discussing the elections to the federal parliament. First of all, these elections highlight the dual nature of Russia’s state structure. On the one hand, it is a very centralised state in which many processes take place simultaneously throughout the country. On the other hand, Russia is so vast that it cannot but be a federation, and regional political (or rather electoral) regimes in neighbouring regions can differ dramatically.

There are three types of regions in Russia: ‘electoral sultanates’, in which official vote tabulations have nothing to do with reality (they are simply made up); regions with a relatively fair vote count; and regions that are somewhere in between. For the sake of brevity, we will call them red, green and yellow. To draw a more objective picture of the election results across the country as a whole, in some (outlined) cases, data from the red zones were disregarded. These zones include the Jewish Autonomous Oblast, Adygea, Dagestan, Ingushetia, Mordovia, Chechnya, Stavropol Krai, and the Tambov and Tyumen Oblasts. About a quarter of all the voters who voted in the regional elections live in these regions.

To be clear, there can be local zones of falsifications in green regions as well. Besides, this classification refers only to the vote count and does not extend to the integrity of the entire election campaign (registration of candidates, equality of their rights in the media, etc.).

Increased political competition at the regional and local levels

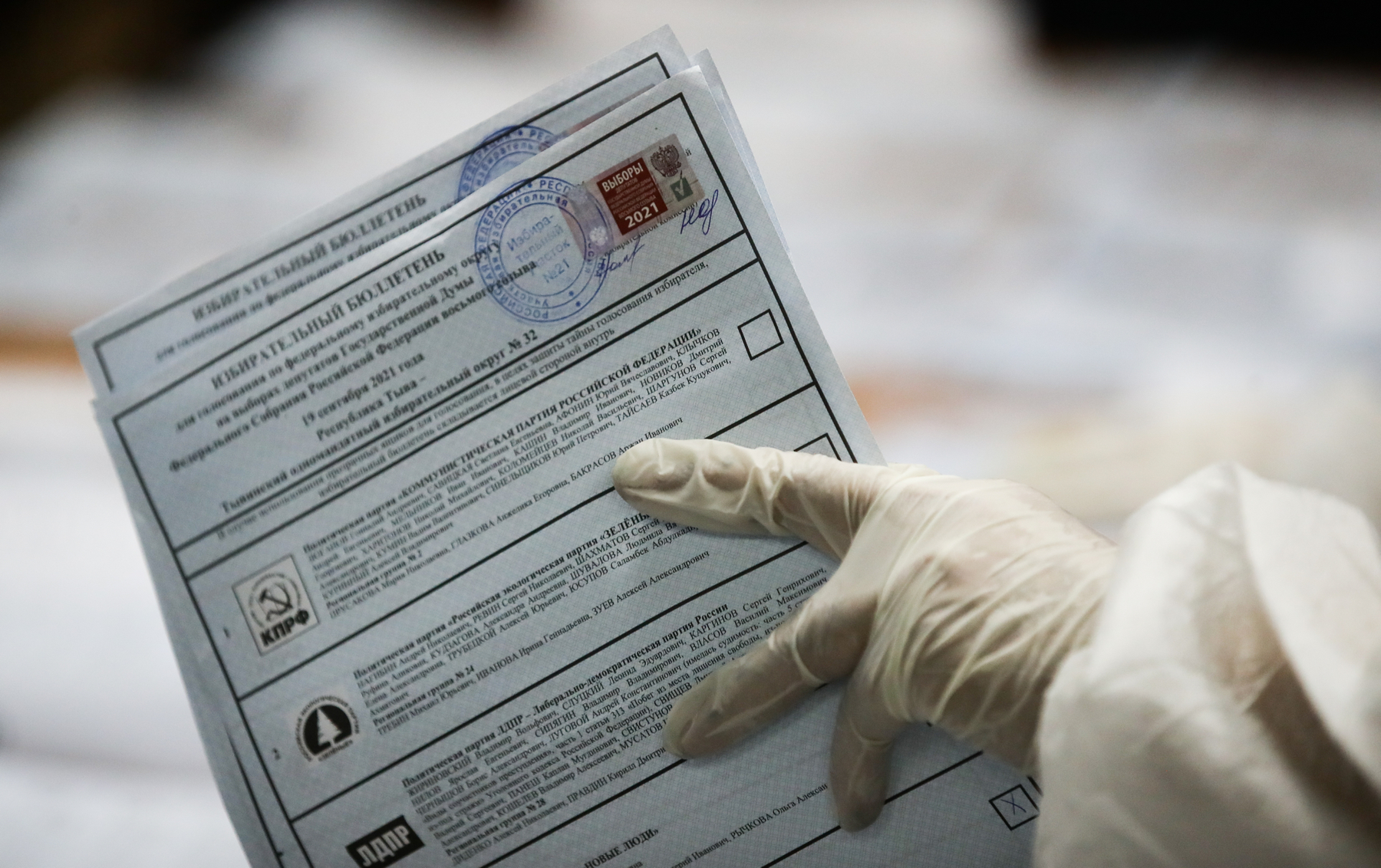

This year, in 39 regional parliamentary elections, 15 political parties were registered – a total of 275 regional party lists. In all 39 regions, however, candidates from only three parties were on the ballot list: United Russia, the Communist Party (CPRF) and A Just Russia – For Truth. The LDPR (Liberal Democratic Party of Russia) did not nominate any candidates in Chechnya. The Party of Pensioners (26 regions), the New People (22), the Communists of Russia (20), Yabloko (14) and Rodina (13) also registered more than 10 regional lists. Fewer than 10 lists were registered by the Party of Growth (9), the Greens (6), Green Alternative (4), the Russian Party of Freedom and Justice (4), Civic Platform (1) and the Party of Direct Democracy (1). Regionally, the competition ranged from three party lists in Chechnya to 11 in Karelia and Samara Oblast. In some cases, the authorities tried to fully control all election contestants and not to complicate their administration of the process; in other places, they tried to dilute the opposition vote as much as possible; and in yet others, they actually simply registered all those who wanted to participate in the elections.

In Dagestan, Chechnya and Stavropol Krai, only three parties (United Russia, the CPRF and A Just Russia) passed the 5% threshold. In Ingushetia, the CPRF failed to gain 5%, but the LDPR did. In Adygea, Mordovia, Leningrad Oblast, Tyumen Oblast and Chukotka, the lists of four old parliamentary parties passed the 5% threshold. All of these regions are in the red zone, except for Chukotka, which has a small number of voters, and Leningrad Oblast, which is close to the red regions. On the other hand, all other regions were more diverse.

The Party of Pensioners was successful in Karelia, Chuvashia, Kamchatka and Primorsky Krais; Amur, Vologda, Kaliningrad, Kirov, Kursk, Lipetsk, Murmansk, Novgorod, Orenburg, Oryol and Tver Oblasts; and Khanty-Mansi Autonomous Okrug – a total of 16 of the 26 regions where it ran in the elections. In the remaining regions, it approached the 5% threshold almost everywhere, and the highest result (10.7%) was achieved in Murmansk Oblast.

The New People gained more than 5% in Karelia, Chuvashia, Kamchatka, Krasnoyarsk and Perm Krais; Amur, Astrakhan, Kirov, Kursk, Lipetsk, Moscow, Nizhny Novgorod, Novgorod, Omsk, Oryol, Pskov, Samara, Sverdlovsk and Tomsk Oblasts; as well as in St Petersburg – that is, in 20 out of 22 regions. The only regions where the New People failed to win were Stavropol Krai and Tyumen Oblast.

The Communists of Russia managed to get into regional parliaments in Altai Krai and Amur and Omsk Oblasts. In all of these cases, they came first on the ballot wherever the CPRF came first in the federal election. These parties have virtually indistinguishable logos and similar names. But the Communists of Russia did not campaign in these regions. Therefore, the party’s results should rather be recognised as a mistake and be added to the CPRF’s results instead.

In Altai Krai, the Communists of Russia won more than 12% of the vote; in Omsk Oblast, 11%; and in Amur Oblast, more than 8%. If the votes cast for the two Communist parties were combined, in Altai, the Communists would get 36%, versus 34% for United Russia. Taking into account the single-mandate districts, which United Russia also lost in many cases, in this region the ‘party of power’ has only 31 seats, the CPRF has 24, the Communists of Russia have four, a Just Russia has five, and the LDPR has four. And while the LDPR tends to take an approach similar to that of United Russia in this region, a Just Russia pursues a fairly independent policy. Were it not for the spoilers from the Communists of Russia, parity between the authorities and the opposition would have emerged in this region – a Just Russia and LDPR would have ‘golden shares’.

This is rather symptomatic. Even in the Lipetsk Oblast, a region with a relatively high level of electoral fraud (although it is in the yellow zone), the CPRF managed to win 12 single-mandate districts out of 28. As a result, United Russia will have 23 seats in the Lipetsk city legislature, while other parties will have 19. Such a close result, obtained thanks to single-mandate districts (which United Russia used to almost always win), is extremely rare.

This time Yabloko managed to get into only three traditional regional parliaments – those in Karelia, Pskov and St Petersburg. There were also real chances of getting into the parliament in the Novgorod Oblast, which has a strong Yabloko branch there. The party’s image was undermined by the recognition of some of its candidates as individuals affiliated with foreign agents. Voters from Novgorod villages found it difficult to understand what this meant.

In Tambov Oblast, Rodina was elected to parliament; in Krasnoyarsk Krai, the Greens; and in the Jewish Autonomous Oblast, the Party of Direct Democracy.

Overall, diversity increased significantly. For example, in Karelia and Amur Oblasts, seven parties entered parliament on party lists, while in Chuvashia, Kamchatka and Krasnoyarsk Krais; Kirov, Kursk, Lipetsk, Novgorod, Omsk, Oryol and Pskov Oblasts; and St Petersburg, six parties entered parliaments. This also has implications for competition in local elections. According to the results of the 17–19 September elections, in 32 out of 39 regions, six to eight parties are entitled to nominate candidates to local and regional elections without collecting signatures.

Major losses

When analysing the 39 different election campaigns, it is very difficult to identify any common trends. However, something becomes noticeable if one counts the increase or, on the contrary, the decrease in the number of votes cast for the parties. In all 39 regions, the previous elections were held in 2016, so this comparison is correct.

First, the number of voters increased by 1,340,116, or 6%, overall. That is, voters in general participated more actively in the last regional elections. Interestingly, this number is comparable to the number of votes cast for the New People, who did not participate in the previous elections. They received about 1.1 million votes in these regions in 2021. It is hardly possible to say that all 1.1 million voters who voted for the New People are new, but it is obvious that they include a significant portion of those who did not participate in the elections five years ago. However, some other parties also increased their results considerably.

Despite an increase in the number of voters, United Russia suffered serious losses: the party received 3.59% fewer votes. This drop is even more significant in green and yellow zones; the number of votes in favour of the party of power fell by 6.87% (a decrease of some 527,000 votes) there. In other words, the drop in support occurred in parallel with the growth in the electoral activity of citizens.

The most devastating loss this year was suffered by the LDPR: its support decreased by 39%–40%. In total, the party lost 1.4 million votes out of the 3.5 million received in 2016. And it is not only the regions of Siberia and the Far East, which were most responsive to the party’s incomprehensible position in the conflict around the arrest of former LDPR governor Sergei Furgal of Khabarovsk Krai. The same thing happened, and on roughly the same scale, with support for the LDPR in Karelia, Chuvashia, Perm Krai, Kirov and Novgorod Oblasts, and other regions far removed from the conflict in the Far East. The Khabarovsk protest has indeed turned out to be a nationwide theme.

Another party that lost a significant portion of its supporters was Yabloko. In 2016, this party received less than 580,000 votes. Moreover, in five years it has lost almost 40% of that support. In fact, Yabloko has finally turned into a regional party: it operates in only 5–10 regions, mostly located in the north-west of the country and in Moscow.

Major gains

Left-wing parties have demonstrated impressive growth this year. Even A Just Russia rose by 15%–16%. But the main breakthrough was made by the CPRF, which increased its support by 35%, or 1.2 million voters (by 37% in the green and yellow regions). Another 430,000 votes were in favour of the Communists of Russia (four times more than in 2016) and 600,000 in favour of the Party of Pensioners. The result of the Party of Pensioners is also interesting because the party gained a significant number of votes in almost every region, but in 10 out of 26 regions it could not overcome the threshold – its potential mandates burnt out somewhere, and were actually diverted to United Russia in some places. This happened because of the Imperiali quota method, which is used in some regional elections to determine the number of seats won by a particular party, and significantly distorts the representation in favour of the winners. This method was used, for example, in Krasnoyarsk, Perm and Stavropol Krais, and Samara Oblast, where the Party of Pensioners failed to gain 5%.

If we add up the votes for the CPRF, the Party of Pensioners and the obvious outliers from the Communists of Russia, this bloc in the green and yellow zones received almost 29% of the votes. United Russia got 40% of the votes in the same regions. And here it should be recalled that, even in these regions, there are areas (sometimes quite large) where the level of fraud is comparable to that of the red zones. That is, the real results should be even closer.

In addition, A Just Russia – For Truth received another 11% of all votes in these two groups of regions. And the LDPR won 10% of the vote. Another 5.6% was won by the New People, which, however, did not take part in the elections in every region (if we count only the regions where they took part, they would have won 7.5% of the vote).

All of these are significant changes, which generally confirm what was evident from the results of the federal elections: United Russia and the CPRF are becoming comparable forces in terms of the level of voter support. At the same time, it is rather the Communists who are seeing gains. This will probably force both federal and regional administrations to take steps in the near future in the hope of adjusting voting results in their favour. And some of these measures have already been announced. Russia’s Central Election Commission wants to change the rights and obligations of members of commissions with the right of a deliberative vote – that is, it continues to attack the right of citizens to observe elections. In the Kirov Oblast, for example, attempts are being made to abandon the proportional system in the upcoming elections for the Kirov City Duma next year, in favour of single-member districts. Admittedly, if the trends continue, the initiators of these changes might be greatly surprised to lose most of the single-mandate districts.

In any case, diversity in the political life of these regions will increase within the next five years since the number of parties participating in the parliamentary work in many regions has increased, and new political forces have appeared. The number of parties that will be able to nominate their candidates without collecting signatures has also increased. It will definitely lead to the revival of public politics in many regions, even if not in the whole country.