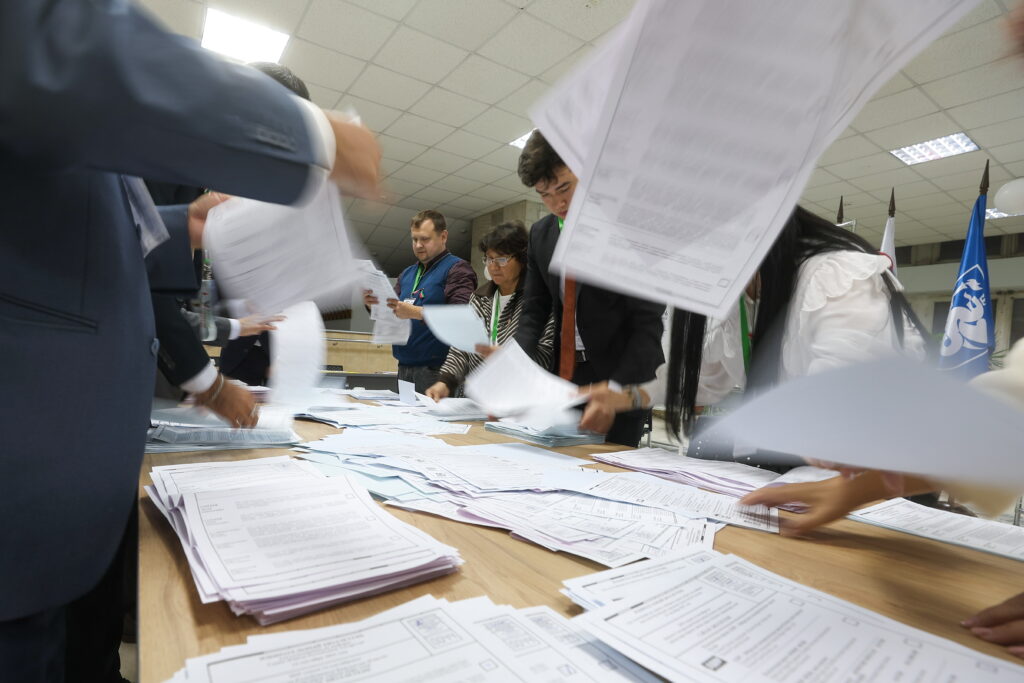

On 10 September 2023, another election in Russia came to a close. Leaving aside the occupied territories of Ukraine, where the Russian authorities also organised voting, the major campaigns included the governor elections in 21 regions, elections of deputies to regional parliaments in 16 regions, and elections of deputies to city councils in the capital cities of 12 regions.

Decreasing levels of real competition

The Golos Movement for the Defence of Voters’ Rights pointed out that 2023 saw a noticeable decrease in the willingness of political parties and individual politicians to participate in elections, regardless of level. When the registration stage ended, with hardly any dropout to be seen this time, the degree of formal competition levelled off, becoming approximately the same as in previous years. However, this formal competition does not fully reflect the reality because not all nominal parties and candidates are real competitors: some of them may turn out to be ‘spoiler candidates’ or simply ‘technical candidates’.

One way for political scientists to assess the actual degree of electoral competition is the effective number of parties or candidates (ENP/ENC). This indicator measures the degree of fragmentation versus monolithicity of the vote. In case where one candidate receives all the votes, the indicator for this candidate will be equal to one. In all other cases, the indicator will be greater but cannot exceed the nominal number of candidates. For example, if four candidates are running and each of them receives an equal share of the vote (25% each), the ENC will be equal to four.

If we compare the ENP/ENC in the current elections and in the elections held five years ago, the decrease in indicator values is highly noticeable. Even in governor elections, which have never been characterised by high competition, the value has decreased from 2.08 to 1.54 on average in the course of five years. The situation could have been slightly better in Khakassia, but the United Russia candidate withdrew a few days before the start of voting. In the elections to regional parliaments, the average ENP was 3.49 in 2018, with 2.64 in 2023 (the highest indicator, 3.6, was recorded in the Yaroslavl Region, where six parties made it to the parliament). The ENP increased only in Kalmykia and remained at almost the same level in Yakutia. In the elections of city council deputies in administrative centres, the ENP also decreased, from 3.83 to 3.05 on average. The highest score this year, namely 4.17, was recorded at the elections of deputies to the City Duma of Veliky Novgorod, where a total of seven parties made it to the parliament.

This is a direct consequence the sharp increase in United Russia’s electoral results, coupled with the weakening of the Communist Party of the Russian Federation (CPRF) and Fair Russia.

Party trends

United Russia was able to improve its results almost everywhere compared to the crisis year of 2018. In most cases, it achieved a very significant increase. Overall, United Russia added almost 900,000 votes to the results achieved five years ago, while the CPRF, the LDPR (Liberal Democratic Party of Russia) and Fair Russia lost more than 1 million votes in aggregate. The growth of the ‘party of power’ is particularly impressive in Buryatia (from 41.1% to 60.8%), Transbaikalia (from 28.3% to 56.9%), Arkhangelsk Region (from 31.6% to 50.2%), Vladimir Region (from 29.6% to 55.5%), Ivanovo Region (from 34.1% to 65.4%), Irkutsk Region (from 27.8% to 54.6%), Smolensk Region (from 36.3% to 57.4%), and Ulyanovsk Region (from 34% to 49.9%). In 2021, some of these regions were classified as highly protest-prone. A similar trend has been observed in administrative centres: a noticeable increase in the results scored by United Russia was recorded in Maykop, Abakan, Krasnoyarsk, Arkhangelsk, Belgorod, Novgorod, Ryazan and Yekaterinburg.

Khakassia was the only place where United Russia lost the elections based on party lists: it scored 36.4% against 39.1% for the CPRF. However, even here, the ‘party of power’ managed to gain a solid majority in parliament since it held a victory in almost all single-member constituencies. As a result, Khakassia will be governed by the Communist governor Valentin Konovalov, who was elected in a competitive campaign, and he will face opposition from the Supreme Council with a majority held by United Russia. However, the situation was the same in the previous five years and, as a result, Konovalov managed to win a significant share of the local elites over to his side. Despite derogatory comments from many pro-government experts, Konovalov is now perhaps the most electorally experienced public politician in the country: no one else can boast the same unique experience in running election campaigns (five rounds of governor elections in 2018 and a fierce struggle in 2023, with efforts to win high-ranking United Russia members over to his side).

The ‘party of power’ suffered a slight decline in Kalmykia and gained hardly anything in Yakutia, Kuzbass and Novomoskovsk Administrative District (NAD). However, in the ‘electoral sultanate’ of Kuzbass, there is simply no room to push the results any further: the party already has more than 69% of official voter support there.

The CPRF lost a significant share of support, partly because of its stance on the full-scale invasion of Ukraine, and partly because it simply did not run a campaign. For example, in the Irkutsk Region, which was until recently headed by a Communist governor Sergei Levchenko, elected in a competitive process, the CPRF’s results more than halved, from 33.9% to 15.5%. At the same time, the party ran a very passive election campaign, one possible explanation being the prison sentence handed down against Levchenko’s son. The party’s results also more than halved in the Ulyanovsk Region with a Communist governor, where five years ago the CPRF received more votes than United Russia. The CPRF was unable to find a niche for itself in a situation where it is not allowed to criticise the regional authorities. As a result, the CPRF lost its status of the ‘main opposition force’: its results are virtually equal to those of the LDPR, and in some places the CPRF lost not only to the LDPR, but also to New People.

The LDPR has also lost some of its support. The most significant losses for the party were recorded in Khakassia (7.2% vs. 20.1% five years ago), Transbaikalia (15.6% vs. 24.6%), Vladimir Region (10.4% vs. 20.8%) and Smolensk Region (11.3% vs. 19.8%), as well as in the NAD (9.9% vs. 17.4%). However, the LDPR managed to get almost 15% in the Arkhangelsk Region, where it did not participate in the last elections at all. The LDPR’s successful campaign for the Krasnoyarsk city council should also be emphasised: the party scored 19.8%, compared to 9.4% for the Greens and only 8% for the CPRF. In other regions, the LDPR remained at approximately the same level (somewhere slightly higher, somewhere slightly lower). It failed to get into the regional parliament in Kalmykia, but this is no news. Importantly, the LDPR overtook the CPRF in the Transbaikal Krai as well as Arkhangelsk, Ivanovo, Kemerovo and Smolensk Regions. However, in Ivanovo and Smolensk Regions it was helped by the Communists of Russia, who took votes away from the CPRF.

Fair Russia has clearly hit a rough patch. Its excessive rapprochement with Yevgeny Prigozhin this spring triggered an exodus of strong politicians and activists from the party. Moreover, this friendship has not been forgotten by some of the regional authorities. For example, in the Rostov Region, where the rebels seized Rostov-on-Don in June, Fair Russia officially received merely 4.81% of the vote and was effectively ousted from the parliament (given that the official results in the Rostov Region are tightly controlled by the regional administration, this result is highly meaningful). In addition, Fair Russia failed to pass the five per cent barrier in Buryatia, Khakassia, Ivanovo and Smolensk Regions and in NAD, and failed to get into the city councils of Maykop and Krasnoyarsk.

As a very young party, New People does not yet have strong regional branches everywhere, so its weak results in some regions are understandable. For example, the party did not participate in the elections to the regional parliament of the NAD at all, and failed to go past the five per cent threshold in Bashkortostan, Khakassia, Transbaikal Krai, as well as Vladimir, Ivanovo, Rostov, Smolensk and Ulyanovsk Regions. However, the party performed very well in Yakutia, where it came second with 14.2% of the vote (and in the city of Yakutsk, where it got 16%). New People also achieved high scores (over 7%) in regional elections in Buryatia, Kalmykia as well as Irkutsk and Yaroslavl Regions, and in the city council elections in Arkhangelsk, Novgorod and Yekaterinburg. So far, New People has evolved into a party of the national republics and the urban electorate, which is certainly an uncommon combination in Russian politics.

The Party of Pensioners performed rather poorly this year. In many ways, this party is an unusual phenomenon in Russia’s regional elections. While it does not engage in any real work, it managed to achieve very good results in the elections of deputies to regional parliaments in previous years. This year, however, its list was registered in just four regions (making it to the parliament in two of them, i.e. Vladimir and Yaroslavl Regions) and eight cities (getting successful in three: Belgorod, Novgorod and Ryazan).

Communists of Russia, considered to be the main ‘spoilers’ for the CPRF, were not that successful this time, either, making it only to two regional parliaments (Ulyanovsk Region and NAD) and to the city councils of Yakutsk and Belgorod. The departure of the Communists of Russia from the Supreme Council of Khakassia (where they received 8% in 2018) is quite meaningful: the much-hyped scandal with the registration of ‘spoiler candidate’ Vladimir Grudinin in the governor election played a cruel trick on them. The technique of using spoiler candidates is based on the fact that voters do not expect to see a ‘double’ and make a mistake when voting. This time, the scandal was all over the headlines so it became very difficult for voters to make a mistake.

Rodina managed to get one list into a regional parliament: it received 5.7% in the election of deputies to the legislative assembly of the NAD.

The Greens list scored very high (9.4%) in the elections of Krasnoyarsk city deputies: the city is suffocating due to the unfavourable environmental situation, so voting for the Greens is quite understandable there. This party overtook most of the ‘parliamentary top five’, namely the CPRF, Fair Russia and New People.

Yabloko deserves a special mention here. This year, it participated in elections to just three city parliaments: in Yekaterinburg, Krasnoyarsk and Novgorod. The results in Krasnoyarsk were unimpressive, with just over 1%, but Yabloko confirmed its status as a local ‘parliamentary party’ in Novgorod and Yekaterinburg. In Yekaterinburg, the party gained more than 9% of the vote (ahead of New People), and managed to get 7.4% of the vote in Novgorod. This was the first time even in Russian history that a party list labelled on ballot papers as affiliated with a ‘foreign agent’ was elected to a parliament.

Representation of parties

As a result, the level of representation at the regional level was low: on average, 4.3 parties per region were elected to regional assemblies. The situation was slightly better in the elections of city councils, with 4.9 parties per region. On average, this indicator is even lower than the number of political parties represented in the federal parliament. This seems to be the first such situation since 1995. The most representative regional parliament was formed in the Yaroslavl Region, with six parties: the ‘parliamentary five’ and the Party of Pensioners. At the level of city councils, Novgorod has achieved the highest representativeness score, with the ‘parliamentary five’ plus the Party of Pensioners and Yabloko. Yakutsk, Belgorod and Yekaterinburg will each have six parties in the city council.

Election results

It is difficult to assess the campaign that has just come to an end. On the one hand, the sharp increase in United Russia’s results is noticeable but, on the other hand, this leap is largely due to the relative inactivity of its main competitors. One could think of a football match where one team is making an effort to win while the other one does nothing and demonstrates its unwillingness to play in every possible way.

At the same time, one can see that wherever the opposition forces are really trying to compete, they achieve high scores. Examples include the CPRF and its governor Konovalov in Khakassia, New People in Yakutia, the LDPR in Krasnoyarsk, or Yabloko in Yekaterinburg and Novgorod.

The time when voters were ready to support any candidate unaffiliated with the current government (as was the case in 2018) is now gone (or has not re-emerged). Nevertheless, voters are clearly ready to listen to the opposition forces and hear their message as long as opposition activists are making a genuine effort, trying to get through to people.