On July 10, Dmitry Peskov unexpectedly announced that the Russian president had already met with Yevgeny Prigozhin and the commanders of the Wagner Group after the mutiny. «This meeting took place at the Kremlin on June 29. It lasted almost three hours. The details of it are unknown. The only thing I can tell you is that the president offered an assessment of the company’s actions on the front in the course of the Special Military Operation, as well as of the events of June 24. The commanders themselves outlined their version of what happened, stressing that they are committed supporters and soldiers of the head of state and the supreme commander-in-chief,» Putin’s spokesman said.

However, on that same day in question, June 29, Peskov also claimed that the Kremlin knew nothing about Prigozhin’s current whereabouts. Most likely, in this way, the president’s press secretary tried to inoculate the public in anticipation of a publication of this story by one of the independent media outlets that might have found out about the meeting. However, in this particular case, the consequences of the inoculation outweighed the potential damage from a possible leak. Peskov often denies information published by independent press, and these tricks seem to work well for an audience loyal to the regime.

The Kremlin’s admission that Putin has met with the Wagner Group should disturb and dismay this public. Propaganda worked hard to convince them that Yevgeny Prigozhin had brought the country to the brink of disaster and civil war. It released footage from his mansion, broadcast the numbers he was due to receive from the public funds according to his multi-billion dollar contracts with the government, and claimed that the capture of Bakhmut (the main achievement of Prigozhin’s private military company) was not all that important for the general situation at the front. This smear campaign worked: Prigozhin’s approval and support ratings plummeted while in the eyes of many Russians he was transformed from a positive figure into a boogey man. Then suddenly this very person found himself at the same table with the President, who had just recently branded the instigators of the rebellion «traitors» and «renegades», although he did not refer to Prigozhin by name.

Nothing has changed in the world of Putin’s opponents: Peskov was lying as per usual, and the authorities could not make up their minds as to what had to be done about Wagner, so they were floundering. Even before Peskov’s announcement, those opposed to the regime had read news reports that Prigozhin was traveling freely across Russia and that the money and weapons seized during the searches of his mansion would be returned to him. Prigozhin’s meeting with Putin was perfectly in line with that same story. For the supporters of Prigozhin, Peskov’s statements are a normalization of the situation and an admission that the Wagnerites were right, that they had a point. Those sympathetic with the founder of the Wagner Group are not anti-Putinists (at least not yet). They do not consider themselves to be an opposition to the Kremlin, and they find it much more comfortable to imagine Prigozhin and Putin at the same table than to see them on the opposite sides of the barricades. Here the Kremlin does score some points, and in a sense, Peskov’s recognition can be considered a step in the direction of Prigozhin’s supporters.

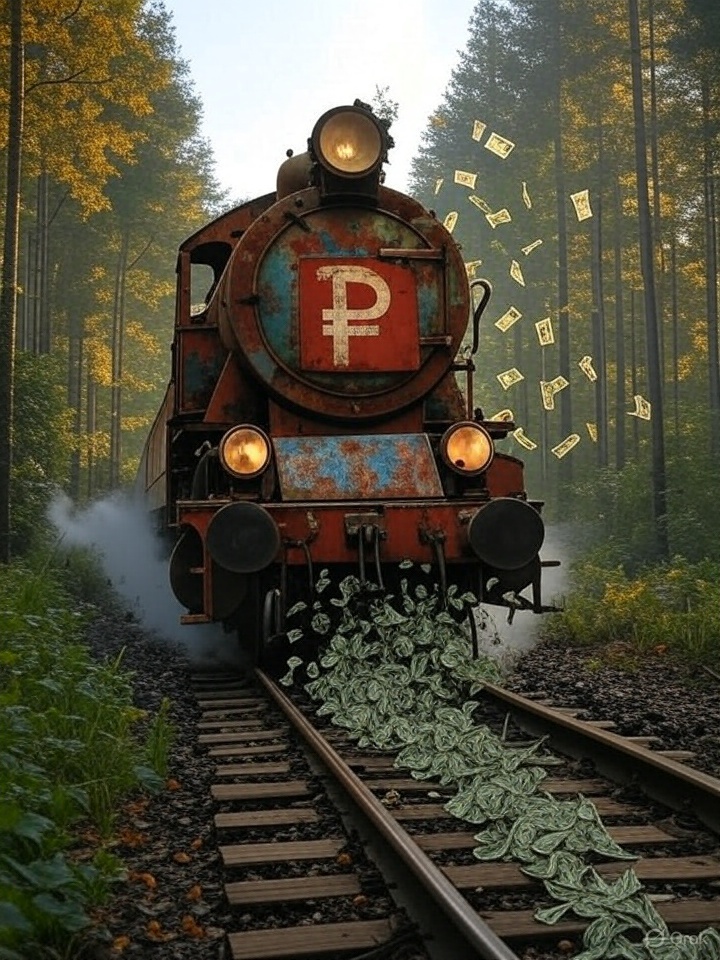

Peskov’s account has a negative effect on Putin’s support group. Thereby loyalists receive a blatant signal from the Kremlin: «We are deceiving you, we are manipulating you.» No explanation as to why the President had met with the «traitors» was offered by his spokesman. No one has disavowed the statements about Prigozhin as an «apostate» and the campaign to discredit the founder of the Wagner Group continues, albeit not as actively as before. Putin’s audience, accustomed to unambiguous interpretations of information and the in sync, streamlined operation of the pro-government media, is facing information schizophrenia. The Kremlin sends them contradictory messages without even trying to harmonize and synchronize these messages in any way. The conclusions that loyalists can draw from Peskov’s words might differ widely. Some of them will suspect Putin of weakness: the alleged «traitor» still managed to procure a meeting with the President, and at most — to resolve some of his own issues. Another group will see through Kremlin’s decoy and manipulation. A yet another group will regard Putin’s actions as inconsistent. Any of these conclusions will erode the government’s support base, but judging by the Kremlin’s fretful treatment of it, the Kremlin is confident that the base voters are going to put up with whatever inconsistency and manipulation comes their way. The power vertical is not keen on spending any energy on maintaining loyalty, although it should ideally do so against the backdrop of the constantly rising prices, underlying fear of mobilization, and escalation at the front. Russian authorities no longer buy loyalty by providing social support and maintaining the illusion of being guided by or concerned with the popular will, but instead, demand this loyalty by default, despite material difficulties and blatant manipulation and lies. Thus, «loyalty thanks to» turns into «loyalty in spite of.»

Picking sides

Another proof of the change in the modality of loyalty is the speech given by the head of the Kremlin’s political bloc, Sergei Kiriyenko, at the Digoria forum for young political scientists. Kirienko demanded that they take a «pro-active stance in life»: «If you stay on the sidelines, you should not be offended that your interests are not taken into account in this new future. Because you did not take part in it.» This official’s statement can be considered a formula of sorts for a new pledge of allegiance for those who in one way or another work for the power vertical. Until recently, the Kremlin did not require them to make public statements of support. Political scientists, political technologists, sociologists, and media professionals could «stay on the sidelines,» working for the regime and receiving material support from it, without making fiery pledges of their proactivism. Work and its practical outcomes were believed to be the main thing. A political technologist managing electoral campaigns of pro-Kremlin candidates did not need to walk around in a «United Russia» T-shirt or make public speeches about his or her unequivocal support for Putin and the war. The same was true for political scientists working with Kremlin research centers. They were allowed to have an opinion, within certain limits, of course, or at least to keep quiet about it if they did. A professional could cynically work for the authorities without publicly supporting them. And from a cynical, pragmatic point of view, this worked well for the regime, as it drew even ideological opponents into its orbit. Now Kirienko raised the entry threshold for loyalty and demands that it be shown publicly, demands that the regime’s supporters pick a side, and not all members of the soft sciences crowd serving the political bloc can agree to these demands. Of course, they will be replaced by the same «young political scientists of Digoria», but in this case the quality of the political bloc’s work will drop even more. As a result, it will fall on those with a «proactive stance in life» who have chosen to side with the Kremlin, to interact with «Putin’s majority.» This clash is unlikely to yield anything good, since political scientists and technologists who have «picked their side,» and thus turned into activists on the payroll, will not be able to establish any dialogue.

General unpleasantness

Since the beginning of the war, the Kremlin has kept well-known and popular generals out of the public agenda. Last year, federal television channels briefly praised Commander-in-Chief of the Aerospace Forces Sergei Surovikin, who became head of the Russian forces invading Ukraine. The general’s PR efforts, however, were quickly rolled back, and Surovikin himself disappeared from the public agenda after the surrender of Kherson and lost his position as the head of the Russian forces deployed in Ukraine. After Prigozhin’s mutiny, Surovikin’s surname became widely discussed again. The general, who in the recent months served as a link between the Wagner Group and the Ministry of Defense, simply vanished. He has either run into trouble with the law enforcement agencies for his cooperation with Prigozhin, or he might as well be taking a break from it all. However, rumors about the general are clearly keeping Russian Internet users on their toes.

By the end of the week, another, much less well-known name of Ivan Popov, commander of the 58th Army, which is currently fighting in the Zaporozhye region, surfaced in the new. A certain MP General Andrei Gurulev shared Popov’s message initially posted in one of the closed chat rooms. In it, Popov tells the military about the unfriendly manner in which he had been sacked and attempts to inform the country’s top leadership about the difficulties at the front and obstacles he faced from his «superiors.» Popov’s statements have spread across the Russian Telegram like wildfire: while Yevgeny Prigozhin is keeping silent the public is yearning for new authorized sources of information about the war.

Gurulev’s decision to share the post of the former commander of the 58th Army has already been condemned by the leadership of the «United Russia» party acting through its general secretary Andrei Turchak. But the persistent search for Surovikin and interest in the hitherto unknown Popov is evidence that a certain part of Russian society itself has begun to take interest in generals. The experience of the past years shows that the public yearns the most for peacemakers from among the military. Such a person may as well appear among Russia’s top generals. For example, in his post the above-mentioned Popov speaks of «Ukrainian servicemen» rather than the «Nazis» or «Banderovites.» In this sense, a military man proves to be much more relevant and sensible than the country’s civilian leadership.