In recent weeks, several former and current major officials, both regional and federal ones, have been arrested in Russia. On July 20, a court sentenced the former St. Petersburg vice-governor Gennady Lovlentsev to a house arrest. Lovlentsev was accused of fraud by Gennady Timchenko, a businessman from Vladimir Putin’s inner circle. Earlier, a criminal case was initiated against deputy Communications Minister Maxim Parshin, who was detained last week while accepting a bribe. Around the same time, former vice-governor of the Ryazan region Igor Grekov and former senator representing this region in the Federation Council Irina Petina were arrested, too. They are accused of taking bribes. A former Federal Security Service colonel Mikhail Polyakov who curates a large network of Telegram channels (according to the law enforcers, the network encompassed such channels as @kremlinprachka and @brief, both very well known in political circles) was arrested on suspicion of extortion. Polyakov used to cooperate with the political blocs of the Kremlin and the Moscow Mayor’s office, and had personal ties to the TV host Vladimir Solovyov. The current spate of detentions of prominent officials deeply integrated in the regime — paranthencially, even former officials remain in the orbit of influential groups to whom they owe their appointments — is quite remarkable. It can be interpreted as an increase in the already quite limitless influence of the law enforcers, who are looking for and finding new and more prominent and high-ranking victims.

Most likely, however, the surge in the number of criminal cases initiated against public officials is a symptom of «normalization» of the power vertical, its adaptation to the war, a signal of the regime’s return to its earlier modus operandi. Disputes among powerful groups that included the use of force that were usually accompanied by the redistribution of property and of the spheres of influence were a familiar marker of Putin’s regime in times of peace. In the late 2010s, the group supporting the then-Prime Minister Dmitry Medvedev was being methodically undermined, and the Magomedov brothers, the businessmen associated with Medvedev, were arrested and eventually received huge prison sentences. Oligarchs loyal to the regime, such as Vladimir Potanin, faced criminal charges. Retired governors and members of their entourage were targeted, too. Former and current officials were on the radar of law enforcers, who had to meet their KPI targets for the number of crimes uncovered and solved. Mayors of large cities and deputy heads of regions routinely ended behind bars.

The outbreak of the full-scale invasion came as a shock to most of Russia’s leadership: Vladimir Putin had not warned the majority of key players about his plans, so they were basically confronted with the fait accompli on the eve of troop deployment. The war itself imposed a kind of moratorium on internal squabbles within the Russian elites, especially the kind of squabbles that involved the use of force. The system had to demonsrate internal cohesion and it did demonstrate just that: a kind of «military truce» was declared within the vertical of power and an unspoken non-aggression pact concluded.

Only those of lesser importance and prominence — for instance, ancillary figures involved in Telegram business — and not the most high-ranking regional officials were targeted by the law enforcers. Things were quiet even in the middle tiers of the power vertical, and if there were attempts to sort things out at this level as well (for example, there were rumors of Ksenia Sobchak facing criminal prosecution), it was all eventually resolved peacefully. In the context of the «martial law» internal unity and cohesion within the fellow circle was more important. By the way, the regime’s (both of the civil authorities and of the siloviki) rather laid-back attitude towards Igor Strelkov, one of the key protagonists of the so-called «Russian Spring» of 2014, was a case in point. In his Telegram channel that has 800,000 followers he regularly criticized Russia’s leadership, including Vladimir Putin, the Defense Ministry, the «Wagner» Group and its founder Yevgeny Prigozhin. Strelkov even established something akin to a political movement called The Club of Angry Patriots. He got away with it all as part of the «military consensus,» but recently the «angry patriot» himself was detained on suspicion of extremism. The vertical of power has thus acted according to its pre-invasion conventions.

During the year and a half of the full-fledged invasion, arrests in the ranks of bureacracy that before February 24, 2022 were a sort of background noise to the news agenda, have turned into high-profile events. Now they are becoming routine again, which means that the vertical of power has fully adapted to the new context and is resorting to its old rules and conventions, while the war is no longer regarded as a force majeure. Law enforcers are again doing whatever it takes to advance their careers, influential groups are weakening each other by launching mutual attacks. Most likely, the arrests among current and former officials, deputies and senators will continue, since for a year and a half of this «military truce» the prominent players have accumulated grievances against each other, and the Federal Security Service, the Interior Ministry and the Investigative Committee had an ample opportunity to compile files of compromising materials regarding each of the players. It was only a matter of time till these files yielde criminal investigations. And now this time has come.

Exhibition of Putinism’s achievements

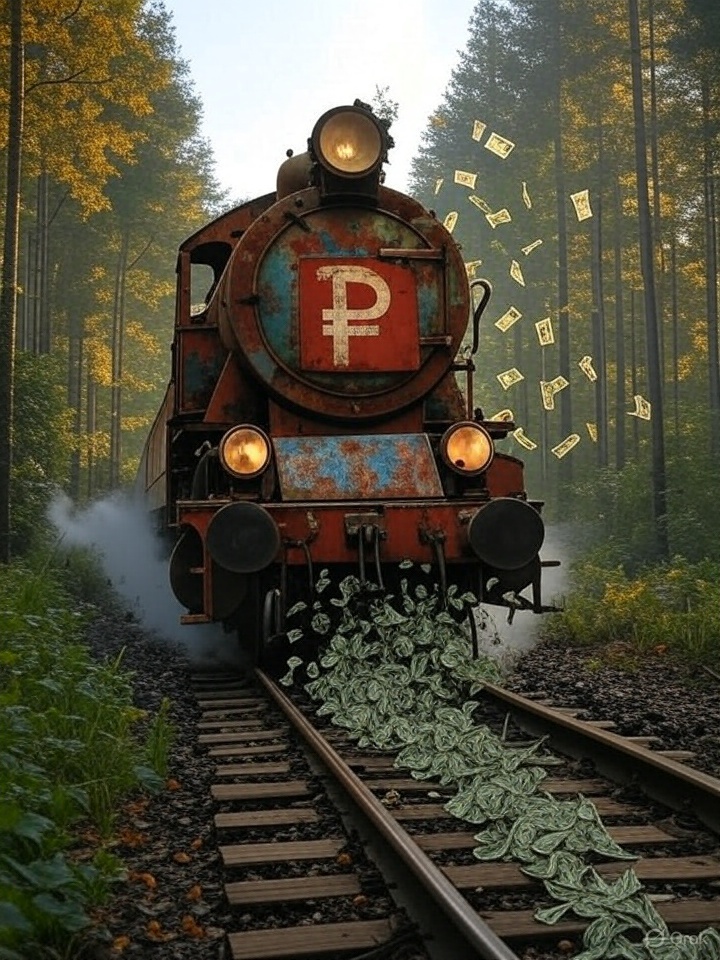

The Kremlin’s domestic political bloc is gradually launching Vladimir Putin’s presidential campaign for the 2024 elections. One of its main elements is a forum-exhibition titled «Russia,» which will start its work on November 4, will last throughout the active phase of the campaign, and end after the elections take place, i.e. on April 12, which is the Cosmonautics Day. The event is supervised by the head of the Kremlin’s political bloc, Sergei Kiriyenko, who also heads its organizing committee. At the forum, which will be held at the Exhibition of Achievements of National Economy or VDNKh, Russian regions, state corporations and enterprises are expected to demonstrate technological achievements in other areas, such as agriculture. The organizers will have to pay special attention to tourism. According to the organizers, the forum is meant to demonstrate to Russians the many achievements of high Putinism. The ambassadors of these many achievements — members of regional delegations, athletes, businessmen and officials — will constitute the «project offices» of the presidential campaign on the ground. The appeal to «successes and achievements» in Putin’s campaign is also a byproduct of the system’s adaptation to war. The parade of technological victories, harvest festivals, and tourist stands are the tools employed by the regime to convince ordinary Russians that everything is going on as before, that nothing terrifying has happened for them. More importantly, it is a sedative for Vladimir Putin himself, who is clearly convinced that the Russian economy is booming, the sanctions are not working, and the war is merely something enfolding in the background. The Kremlin’s domestic political bloc knows how to prepare such magical potions, and the main addressee of their messages, the president himself, is likely to appreciate the efforts. Putin loves the events organized for him by Kirienko and his team. This week he was clearly pleased to talk to participants of the career contests organized by the Presidential Administration. He is also likely to appreciate the showcase of his regime’s achievements. Whether a wider audience will appreciate the forum just as much is a controversial question which is a subject of debate. With the decline in the value of the national currency and the concomitant hike in prices, the electorate might not like the expensive exhibition of achievements all that much.

Losses among the «old guard»

The political bloc of the Presidential Administration is gradually ousting representatives of the old political school from their prominent positions. After the September elections, ultra-conservative Yelena Mizulina, who now represents the Omsk Region in the Federation Council, will lose her senatorial status. The region’s new acting governor, Vitaly Khotsenko, who previously worked in the annexed Donetsk People’s Republic and Stavropol Krai and who had nothing to do with Omsk before being appointed as the region’s acting governor, did not include Mizulina in his list of candidates for the Federation Council. Mizulina will be replaced by Ivan Yevstifeev, deputy head of the federal territory of «Sirius» (a special region formed around the eponymous educational center, which Putin is very fond of). Evstifeev is a local bureaucrat with experience at the federal level, and Sergei Kirienko just loves such characters. For a long while now, the Federation Council has been a kind of place of honorable retirement for well-known regional and federal politicians, former governors, mayors, public system politicians, and Mizulina is a good case in point. Now Kirienko is changing the rules of the game. In 2021, he brought a non-small number of technocrat bureaucrats into the State Duma. Now the time has come to do the same in the Federation Council. Former governors, such as the LDPR representative Alexei Ostrovsky in the Smolensk region and Alexander Burkov in the Omsk region — have already been denied senatorial appointments. Both former regional leaders went to work for their own parties. Kirienko is turning all political institutions into bureaucratic machines loyal to the Kremlin, with no specific features, no brand, and no face. And this, too, is an evidence of the system’s adaptation to the war and its «normalization» as we are witnessing the first deputy head of the Presidential Administration returning to his business of erecting a corporate state.