In the nearly four years since Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine on February 24, 2022, a substantial body of evidence has accumulated showing that external observers often have a severely limited and frequently distorted understanding of the repressive reality in today’s Russia. Yet a clear grasp of the true scale of these repressions is essential, not least for shaping a more effective and consistent Western policy toward Moscow.

The Evolution of Repression: From Gradual Acceleration to Explosive Growth

Political repression in Russia did not, of course, appear out of nowhere on February 24, 2022. It had long become a comprehensive instrument of state control over society well before that grim milestone. Even if we confine ourselves to the harshest form—deprivation of liberty through politically motivated criminal prosecutions—the trajectory of such measures reveals much about the development of Russia’s authoritarian regime.

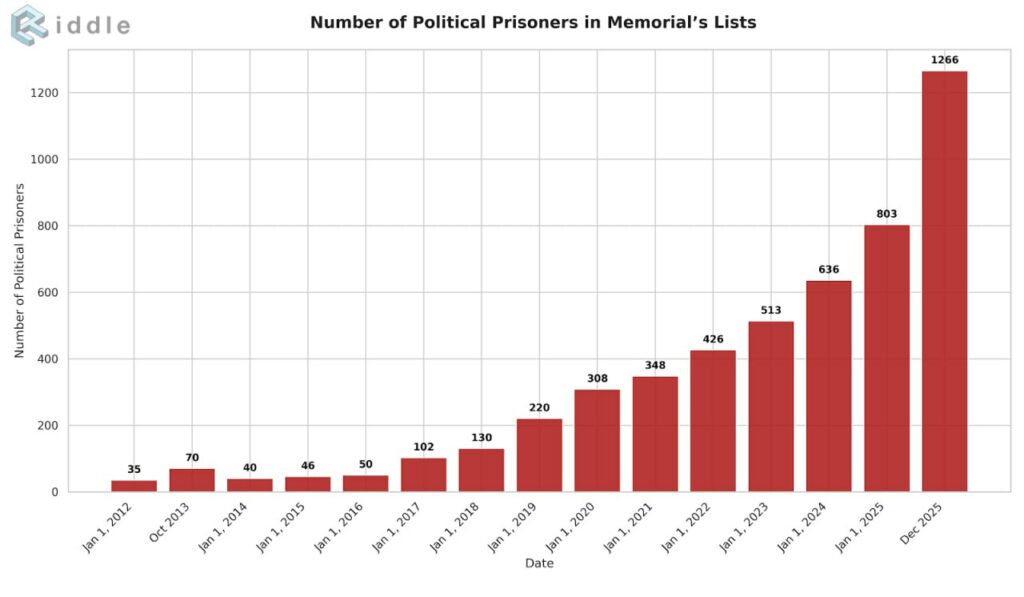

The «Support for Political Prisoners. Memorial» project (until 2022, the political prisoner support program of the Memorial Human Rights Center) has maintained lists of political prisoners in Russia since 2008, based on the definition adopted by the Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe in 2012 (and previously on Memorial’s own nearly identical formulation). Despite the inevitable incompleteness of these data—particularly in recent years, when they reflect only a verified lower bound of repression and inevitably lag behind events—they clearly delineate the overall trend.

The repressive machinery gathered speed gradually, with only one notable pause at the end of 2013, when Putin released most political prisoners ahead of the Sochi Olympics. The pace accelerated sharply after 2020, following the adoption of constitutional «amendments,» the designation of Alexei Navalny’s structures as extremist, and his own imprisonment.

Around the same time, Belarus saw an explosive surge in political repression (even after some releases of prisoners of conscience, at least 1,100 political prisoners remain in Belarusian jails—in a country with a population fifteen times smaller than Russia’s). Unlike the Belarusian regime, which was responding to a direct challenge, the Russian authorities faced no comparable threat at the time. It appeared they were preparing in advance for something far larger. The logic of their actions became clear only in 2022.

The full-scale invasion of Ukraine demanded a new level of societal control—and, accordingly, a new scale and quality of repression.

A New Phase of Repressions in Russia Post-2022: Legislation and Practice

The evolution of political repression in Russia since the full-scale invasion of Ukraine in 2022 can be characterized by three main developments: the introduction of draconian new legislative measures, a significant tightening and simplification of enforcement practices, and a sharp increase in the number of victims of politically motivated prosecutions.

The most prominent provisions targeting opponents of the war are those criminalizing the «dissemination of knowingly false information about the Armed Forces of the Russian Federation» (Article 207.3 of the Criminal Code, punishable by up to 10 years’ imprisonment) and the «discreditation» of the armed forces (Article 280.3, up to 5 years). These were enacted almost immediately after the invasion, in March 2022.

The scope of new repressive legislation, however, extends far beyond these headline measures. Among the most illustrative are:

- Up to 8 years for confidential cooperation with a foreign state or organization (Article 275.1);

- Up to 6 years for calls to engage in activities directed against state security (Article 280.4);

- Up to 5 years for facilitating decisions of international organizations in which Russia does not participate (Article 284.3);

- Up to 4 years for repeated public display of extremist or other prohibited symbols (Article 282.4);

- Up to 3 years for operating on Russian territory on behalf of a foreign or international NGO without official registration (Article 330.3);

- Up to 3 years for calls for sanctions against Russia or Russian individuals and legal entities (Article 284.2).

In addition, the war has prompted severe penalties for voluntary surrender to the enemy (Article 352.1), aiding subversive activities (Article 281.1), training for such activities (Article 281.2), and forming subversive groups (Article 281.3), among others. Many of these provisions have been repeatedly toughened; for instance, in November 2025 the age of criminal responsibility for terrorism and sabotage was lowered from 16 to 14.

The war has also led to the broadening of existing offense definitions, the simplification of prosecution procedures, and harsher penalties under a range of Criminal Code articles, including high treason, espionage, participation in foreign armed formations, activities of «undesirable organizations,» failure to fulfill obligations as a «foreign agent,» establishment of NGOs deemed to infringe citizens’ rights, draft evasion, and others.

A defining feature of the new legislation is the vagueness of its wording and the subjective nature of the prohibitions. There is, for example, no legal definition of «discreditation,» while the interpretation of «state security interests» is left entirely to the discretion of law enforcement and the courts.

This linguistic ambiguity is compounded by profound changes in enforcement practice. Russia’s official rejection of «alien Western values”—including standards of fair trial and human rights more broadly—coupled with its withdrawal from the Council of Europe and numerous international treaties, has largely eliminated the need to maintain even the pretense of adversarial judicial proceedings.

Thus, any expression of disagreement with the war is routinely classified as «discrediting the use of the armed forces» (Article 280.3) without requiring evidence. For instance, Elena Abramova from St. Petersburg received a two-year sentence for a solo picket holding a sign reading «No to War!» Denis Ezhov from annexed Crimea was sentenced to one year for publicly shouting «Glory to Ukraine—everything will be Ukraine!» Oleg Orlov, a 70-year-old human rights defender and co-founder of Memorial, was given two and a half years for stating: «The bloody war unleashed by Putin’s regime in Ukraine is not only the mass murder of people and the destruction of infrastructure, economy, and cultural sites in that remarkable country. It is not only the destruction of the foundations of international law. It is also the heaviest blow to Russia’s own future.» Nineteen-year-old student Daria Kozyreva received two years and eight months for affixing a sheet with lines from a Taras Shevchenko poem to the pedestal of his monument.

Even more egregious from a legal standpoint is the application of the graver charge of disseminating knowingly false information about the actions of the armed forces (Article 207.3). In practice, this provision effectively reverses the presumption of innocence: Russian courts deem any information diverging from official Ministry of Defense statements to be false. The accused is presumed to be aware of those statements and to recognize the falsity of anything contradicting them. Prosecutions under this article most commonly arise from posts about alleged Russian war crimes in Ukraine—mass killings of civilians in Bucha and Irpin, strikes on the Mariupol theater and Kramatorsk railway station, and residential buildings in Dnipro, Uman, and other cities. At least 25 people have been sentenced to prison terms solely for posts about the Bucha tragedy. The longest sentence—eight and a half years—was handed to prominent opposition politician Ilya Yashin for discussing Bucha in a video.

Charges of spreading «fakes» about the military are not limited to social media posts or references to war crimes. Siberian journalist Mikhail Afanasyev received five and a half years for reporting that several National Guard officers had refused to participate in the war. Moscow resident Yuri Kokhovets was sentenced to five years for criticizing the war during a street interview. Sixty-eight-year-old pediatrician Nadezhda Buyanova received five and a half years for allegedly telling a patient that Russian forces in Ukraine were a legitimate target for the Ukrainian armed forces. The first person convicted under this article was municipal deputy and lawyer Alexei Gorinov, who received six years and eleven months for remarks made at a local council meeting: «Combat operations are taking place on the territory of a neighboring sovereign state; our country is committing aggression… Children are dying every day—nearly a hundred children have already died in Ukraine.»

Enormous scope for arbitrary application also exists under Article 205.2 (public calls for terrorism, justification of terrorism, or propaganda of terrorism), which has recently become the primary tool for prosecuting speech. Sentences of up to seven years are imposed, for example, for any positive mention of organizations designated as terrorist in Russia—particularly Ukrainian formations such as Azov, Aidar, the Freedom of Russia Legion, or the Russian Volunteer Corps. Grounds for prosecution can also include positive or even neutral assessments of Ukrainian strikes on Russian targets or rhetorical wishes for the death of occupiers or of Putin personally. At least 27 people are currently imprisoned for allegedly «justifying» attacks on the Crimean Bridge.

Sociologist and commentator Boris Kagarlitsky was sentenced to five years for stating that, from the Ukrainian perspective, the Crimean Bridge was a legitimate target. A couple from Leningrad Region, Anastasia Dyudyaeva and Alexander Dotsenko, received three and a half and three years respectively for placing postcards in a supermarket containing the line «Putin to the gallows.» Yaroslav Shirshikov from Yekaterinburg was given five years for saying he felt no sympathy for the killed pro-war blogger Vladlen Tatarsky. Konstantin Ogoltsov from Chelyabinsk received six years for calling the commander of the Freedom of Russia Legion a «true hero» and writing that the Azov battalion was defending its homeland and that its members were, if not heroes, at least patriots.

Even indirect or veiled expressions of dissent can be prosecuted under a wide array of other Criminal Code articles. Former Bauman University lecturer Alexander Nesterenko was recently sentenced to three years for posting several Ukrainian songs on VKontakte—convicted of calls to extremism (Article 280.2), though initially also charged with inciting hatred (Article 282). Krasnoyarsk resident Igor Orlovsky, sentenced to a total of seven and a half years on multiple political charges, received two of those years for «rehabilitating Nazism» (Article 354.1) after comparing Stalin to Hitler as aggressors.

Arbitrariness is no less evident in the far harsher prosecution of protest actions. Since the full-scale invasion, and especially after the September 2022 mobilization, arson attacks on military enlistment offices and other administrative buildings have become widespread. Identical acts are classified inconsistently—sometimes as property damage (Article 167, up to 5 years), sometimes as hooliganism (Article 213, up to 8 years), and increasingly as terrorism (Article 205, up to 20 years). Over time, the proportion of terrorism charges has steadily risen; today the majority of such arson cases are prosecuted under this article.

In the absence of legal avenues for dissent, these arsons have effectively become symbolic anti-war statements. In the overwhelming majority of cases, they involve empty buildings at night, cause either negligible damage (quickly extinguished) or no fire at all, and many attempts are thwarted at the preparation stage. Legally, such acts fall squarely under intentional destruction or damage to property by arson (Part 2 of Article 167), which carries a maximum of five years and does not criminalize preparation. To qualify as terrorism (Article 205), prosecutors must prove intent to intimidate the population. In practice, however, courts almost never require such proof, treating intimidation as self-evident and thus enabling far harsher sentences.

For example, two young men from Chelyabinsk Region, Alexei Nuriev and Roman Nasryev, slightly scorched two small patches of linoleum while attempting to set fire to a military registration desk; each was nevertheless sentenced to 19 years—not only for the unsubstantiated terrorism charge but also for allegedly undergoing training for terrorist activity (Article 205.3) simply for preparing the act. Volgograd resident Igor Paskar received eight and a half years for terrorism plus vandalism (Article 214) after setting fire to a doormat in front of an FSB office. Minor Yegor Balazeikin, detained while still a schoolboy, was sentenced to six years for attempted terrorism after two alleged attempts to arson a military enlistment office that produced no flame—one of which went unnoticed until he himself mentioned it.

One of the gravest and increasingly common charges is high treason (Article 275). Grounds now include not only dubious and poorly evidenced claims of cooperation with Ukrainian intelligence or transmission of open-source data, or intent to join Ukrainian forces, but virtually any financial transfer to Ukraine, arbitrarily interpreted as providing material support to a foreign actor acting against Russia’s security. Schoolteacher Daniil Klyuka received 20 years for transfers to relatives in Ukraine, with the added charge of financing terrorism (Part 1.1 of Article 205.1) on the grounds that the money was supposedly destined for the Azov regiment. Train driver Ostap Demchuk from Amur Region was sentenced to 13 years for transfers to his mother in Ukraine.

Long sentences are routinely imposed even for tiny sums: transgender activist Mark Kislitsyn from Moscow received 12 years for $ 10; Tomsk student Tatiana Laletina 9 years for $ 30; Khabarovsk resident Tamara Parshina 8 years for a similar amount; Moscow IT specialist Nina Slobodchikova 12 years for $ 62; and Sverdlovsk Region mechanic Yevgeny Varaksin 12 years for the equivalent of about $ 22.

Particular attention should be drawn to the new Article 275.1 on «confidential cooperation with a foreign state, international or foreign organization.» It punishes the establishment or maintenance of confidential relations aimed at assisting activities «knowingly directed against the security of the Russian Federation.» Almost any non-public interaction can be deemed confidential cooperation, and the «knowingly directed» element is usually presumed rather than proven for any foreign contact. Often dubbed «treason-lite,» the article carries up to 8 years (versus potential life imprisonment under Article 275), requires no proof of harm, and demands far less evidentiary rigor. It is frequently used when fabricating a full treason case proves too cumbersome. By the end of 2025, over 100 people had already been convicted under this provision.

In 2024, the overall acquittal rate in Russia stood at around 0.25 percent. For politically motivated cases, acquittals have been virtually nonexistent for years. Courts routinely accept prosecution evidence without question. In political trials, common «evidence» includes testimony from secret witnesses, unsubstantiated FSB certificates claiming anonymous contacts belong to Ukrainian intelligence, and commissioned linguistic expert reports that almost invariably find the required elements—calls to terrorism or extremism, justification of terrorism, incitement to hatred, etc.

Reports of torture in politically motivated cases have surged, most often immediately after arrest to extract confessions. In terrorism cases, this has become near-systematic. When defendants retract confessions in court, judges typically ignore the retraction and base convictions on the initial statements obtained during investigation. Convictions resting solely or primarily on subsequently disavowed confessions are commonplace.

Another disturbing trend is the growing opacity of the judicial system: more trials are held in closed sessions, verdicts are increasingly withheld from public court websites, and even defendants’ names and hearing dates are frequently concealed in political cases.

Judicial decisions have also acquired a distinctly ideological flavor. In political sentences—including those for terrorism or treason—courts often cite as evidence of guilt the defendant’s negative attitude toward the authorities and the president’s policies, disapproval of the «special military operation,» participation in protests, or subscription to opposition channels and accounts.

The Functionality of Repression and Potential for Further Growth

The combination of new punitive legislation and a far more «flexible» approach by investigators and courts have produced a dramatic expansion in the scale of repression.

As noted, the Memorial list of political prisoners represents only a lower bound. Our estimate places the total number of individuals deprived of liberty by Russian authorities in connection with clearly politically motivated and unlawful prosecutions at no fewer than 4,800.

This figure excludes thousands of Ukrainian civilian hostages held without legal basis in incommunicado conditions but includes Ukrainian citizens (including POWs) facing criminal charges. Repression against Ukrainians is markedly more brutal: torture is closer to the norm, and rights violations are far more extensive than those experienced by Russian citizens on Russian territory. Of the estimated 4,800, roughly one-quarter are Ukrainian citizens and at least 3,600 are Russian citizens.

The trajectory of politically motivated imprisonments shows that, after an initial surge following the full-scale invasion, the rate of new prosecutions on Russia’s internationally recognized territory has stabilized over the past two years. However, given the length of sentences, the total number incarcerated continues to rise steadily. In 2025, approximately five people per day face criminal charges with clear signs of political motivation. Around 72 percent are remanded in custody either during investigation or upon conviction—a historical record.

Amid relatively stable intake, a key trend has been a structural shift toward graver charges. By the third quarter of 2025, roughly 45 percent of new politically motivated cases fell under «terrorist» articles (including not only terrorism proper but calls, justification, participation, and aiding terrorist activity)—another historical peak.

An even sharper increase is seen in crimes against state security, primarily treason and confidential cooperation with foreigners. In 2025 their combined share rose from 16 percent to 29 percent of all new political cases. Treason alone became the single most common charge, accounting for around 21 percent of new cases. The annual number of new treason prosecutions rose from no more than 13 in 2021 to at least 328 in the first nine months of 2025.

This dynamic can be explained by two factors. First, the regime seeks to maximize intimidation and stigmatization of disloyal citizens through the most frightening labels—treason and terrorism. Second, the FSB’s role in political repression has grown dramatically: crimes against state security fall exclusively within its investigative remit, while terrorism cases can and often do as well.

Charges under the relatively new «anti-war» articles on discrediting the military and spreading «fakes» (as well as traditional «extremist» articles) are gradually being supplanted by accusations of public calls to terrorism and its justification—these heavier provisions are becoming the primary instrument for suppressing free speech. In 2025 alone, the share of the two flagship anti-war articles fell from 7 percent to 4 percent, while calls to or justification of terrorism rose from 14 percent to 18 percent. This trend has been evident for at least the past two years.

Thus, charges that even many regime loyalists recognize as tools for stifling dissent are being replaced by terrorism accusations whose political underpinning is far less obvious to the general public without close examination.

In summary, political repression in recent years has clearly intensified: sentences have lengthened, convictions under the gravest articles (treason, terrorism) have reached record highs, and the victim count continues to grow. At the same time, measured as a proportion of the population directly subjected to politically motivated criminal prosecution, the scale remains comparatively moderate—especially relative to Belarus (where the per capita rate of political imprisonment is significantly higher) and, even more so, the Stalinist period of the 1930s-1950s.

This scale likely reflects the «functional» nature of current repression: it provides the regime with adequate control at minimal cost. Several thousand imprisoned for political reasons (plus thousands facing criminal charges without incarceration and tens of thousands prosecuted administratively) suffice under present conditions. Several factors facilitate this efficiency. First, the modern information environment vastly amplifies the deterrent effect of even targeted repression. The variety, unpredictability, and broad social and geographic reach of charges foster a widespread mindset of keeping one’s head down. Second, society has been conditioned over 25 years of deepening authoritarianism to accept the status quo as inevitable and without alternative.

Mass emigration of hundreds of thousands of the least loyal citizens has further reduced internal pressure. To minimize their influence and stigmatize them domestically, the regime has expanded in absentia political convictions. Their exact number is unknown, but the legal framework and pace are both growing. One illustrative case is the in absentia sentence that entered force in November 2025 against the author of this article: six years for alleged public justification of terrorism—for condemning the unlawful prosecution of Ukrainian POWs.

There are strong grounds to believe that the current level of repression, broadly commensurate with the challenges the regime currently faces, retains considerable room for expansion. Should new serious threats emerge, the authorities stand ready to exploit that potential swiftly. The unprecedented crackdown following the January 2024 protest in Bashkortostan’s Baymak—now involving around 80 defendants, with trials ongoing—serves as a clear demonstration.

It should be noted, finally, that conditions on occupied Ukrainian territories are far worse. While Russia proper saw roughly 1.4 new politically motivated criminal defendants per 100,000 population in 2024−2025 (relatively stable), the figure for occupied Crimea in 2025 reached 5.3, and for the remaining occupied regions (Donetsk, Luhansk, Zaporizhzhia, and Kherson oblasts) 10.2—approximately 3.8 and 7 times higher than in Russia, respectively. Unlike inside the Russian Federation, the number of new political cases on occupied territories rose 30−50 percent in 2025 compared to the previous year.