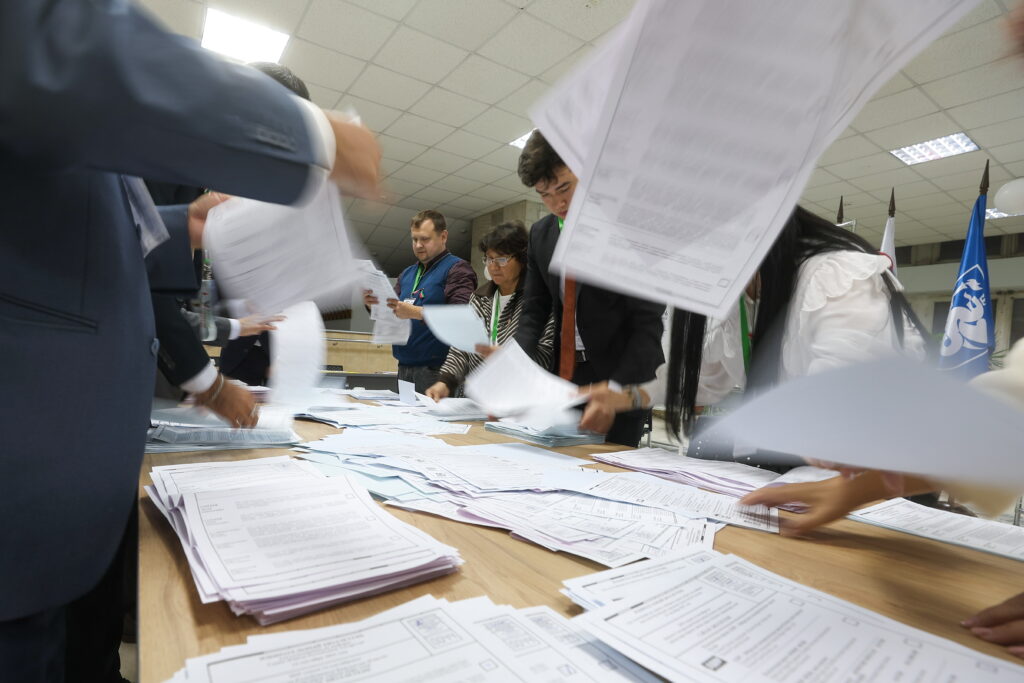

Elections for Russia’s 2024 Single Day of Voting have begun. A total of 4,135 election campaigns are being held across the country, including by-elections for State Duma deputies in three districts, gubernatorial elections in 21 regions, elections for deputies to 13 regional legislatures, 20 city councils and two mayors of regional capitals. Tens of thousands of mandates will be distributed in these elections, of which 98−99% are mandates at the local government level.

No money

These elections are taking place against a background that is far from favorable for the authorities. It is not only the fact that part of the Kursk region is currently under the control of the Ukrainian army — after all, this situation has a direct impact on a limited number of people in a very small area on the scale of a country, although it naturally affects the general mood. But more important is the growing socio-economic tension. For example, since July 1, housing and utilities prices have risen significantly throughout the country (except in St. Petersburg, where prices have been frozen because the regime needs to ensure the re-election of the current governor, Alexander Beglov, who is highly unpopular with the population). Public transport fares and food prices have risen, cars and spare parts have become much more expensive, the program of subsidized mortgages has been stopped, etc.

Add to this a number of regional problems, such as spring floods in the Orenburg and Kurgan regions (both of the regions are currently holding gubernatorial elections), large-scale forest fires in the Transbaikal and Khabarovsk regions (also holding important elections), the invasion of the AFU into the Kursk region (holding gubernatorial elections), problems with coal exports in Khakassia and Kuzbass (holding important elections) — the list goes on and on.

No candidates

It seems that under such circumstances there are enough conditions for a protest vote. Moreover, the very range of the regions where the elections will be held is obviously challenging for the authorities. For example, there is the perennially problematic Altai Republic, where the former Secretary of the «United Russia» party General Council Andrei Turchak was exiled [to serve as head of the region], as well as the equally problematic Transbaikal and Khabarovsk Territories, Khakassia, which surprised the observers with a competitive gubernatorial campaign a year ago, and the Irkutsk Region, that has the history of some of the most massive and persistent public protests in the country.

But there aren’t enough conditions and, above all, a dire shortage of appropriate candidates to enable protest voting. Statistics show that at almost all levels the indicators of competition (even formal) show anti-records. For example, in the elections of regional heads, on average seven candidates per region were nominated (this is a lot, but such a figure was achieved due to the fact that in St. Petersburg 22 people were nominated at once, most of whom had no chance to be registered). If we compare it with 2019, when the last gubernatorial elections were held in most of these regions, the difference is striking: back in 2019, there were 10.2 candidates per seat. In the elections to the local assemblies, an average of 6.3 lists per region were nominated, while 6.2 were registered. The previous record was set in 2018: 8.7 lists were nominated and 6.4 were registered. The situation is similar in the elections to city councils: the rate of nomination and registration is lower than in 2019, with which this year coincides in seven cities, and lower than in 2020, 2022 and 2023 (it was even lower only in 2021, when there were elections to the State Duma, which took away a lot of resources from the parties).

If we look at an even lower level of elections — small towns, rural districts and settlements — the situation is even worse. According to the Golos movement, in the elections of deputies to representative bodies of local self-government that took place during the year between the individual voting days, the average number of nominated candidates was less than two per mandate (1.9). This means that a large number of elections at the local level must be cancelled simply because there is only one candidate left on the ballot at the time of voting. To avoid this, local governments have to find not only the main candidate who must win, but also «technical» candidates who will ensure that the elections are held to begin with.

In other words, politicians just choose not to run at all. In private conversations, many people say they are waiting it out: their job is to «survive for the next three to five years, and then we will see.»

The odds are small, the risks are high, and the benefits are not obvious

Their strategy is understandable. If you are not initially a candidate approved by the authorities, your path will be thorny and almost aimless. It is quite easy to weed out a candidate from the elections. Self-nominated candidates and representatives of parties who collect voters’ signatures in support of their nomination are disqualified from taking part in the elections with the help of handwriting experts from the Ministry of the Interior: these «experts» can invalidate any voter’s signature. There are other tools to stop independent candidates from running in the elections.

Those willing to run in the gubernatorial elections are weeded out through the s-called «municipal filter» mechanism. The Communists have been particularly affected this year, and that in itself is telling. CPRF candidates have particular difficulty registering at times when voters are turning to domestic rather than foreign policy issues. For example, the CPRF had to skip a large number of gubernatorial elections in 2019 and 2020 (there were few gubernatorial elections in 2021, so we’ll leave that year out of the analysis). In 2022 and 2023, in the context of profound shock waves that affected both the public and the political class, the situation changed: the CPRF was allowed to run almost everywhere because it had little chance of causing problems. This year, the CPRF’s forced drop-out rate has returned to pre-war levels. This means, by the way, that the authorities themselves see the potential for protest and are trying to nip it in the bud at the polls.

For elections at all other levels, there are universal tools for weeding out undesirable candidates at the top of the ballot: the mechanism of arbitrarily labeling a person as a «foreign agent» or an «extremist». In both cases, a citizen is deprived of the opportunity to participate in elections.

Even if you pass through all these sieves and then win the election in an extremely uncompetitive and unequal struggle, within one week of receiving the mandate you can still be recognized as a «foreign agent» and your mandate can be revoked: all that is needed is the signature of an official of the Ministry of Justice, no court decision is necessary.

Even if this does not happen, politicians get very limited mandates. At the local level, their authority is almost nonexistent. Even in large cities, the budgets are practically an extended budget of the Education Committee (City Education Committee): more than half of the expenses are eaten up by schools and kindergartens, and together with other «protected categories of budget expenditures,» i.e., those that cannot be changed, this share often exceeds 100% of the city’s own budget revenues. In rural areas the situation is even worse. But even governors (with a few exceptions, such as Kadyrov and Sobyanin) have an extremely limited mandate and cannot even appoint their deputies and key ministers without the approval of the relevant federal authorities.

What they have plenty of, though, is the chance to get into legal trouble and have a criminal case brought against them. Almost every week in Russia cases are brought against mayors, regional ministers, and vice-governors. We are not even talking about the members of the opposition, but about the so-called «systemic» bureaucrats — those that consider themselves to be loyal members of the system of government. It is just that the budgetary and administrative system itself is intentionally designed in such a way that it is practically impossible to solve the problems of local residents without breaking the law. Under such conditions, politicians have very little motive to seek election anywhere.

«Elites can’t and people don’t want to…»

As a result, in the current elections we have a situation where people have grounds for discontent, but there are no candidates through which they could express it. We can paraphrase Lenin’s famous formula «elites can’t and people don’t want to»: «The citizens cannot find their candidates, and the candidates do not want to run.»

In this sense, it is not quite correct to accuse society of passivity. In reality, it is the political class, which is passive, and people just have no one to join and no one to follow or support. It is not even clear what to do, because the political class not only does not participate in the elections, it is altogether silent: it is intent on sitting it all out and is passively waiting for some future opportunities.

The motivations of these silent politicians are clear and understandable: in democratic countries (and elections are an instrument of democracy) there is rarely experience a situation when it takes courage, not just political ambition, to participate in elections. In today’s Russia, however, participation in elections often requires courage and at the same time spells the death of one’s political ambitions.

However, there are exceptions even in such a situation, but they are mainly noticeable at the lower level (and occasionally in the elections of regional deputies). For example, this year’s mayoral election in Bratsk, the second largest city in the Irkutsk region and a major industrial center, is an example of a highly competitive campaign. There, two «United Russia» party candidates running for mayor: the mayor of Bratsk, backed by the governor and the «United Russia» party itself, and the mayor of the surrounding Bratsk district, backed by a senator from the Irkutsk region. As a result, we are witnessing an interesting campaign in which the police are confiscating illegal copies of the official municipal newspaper of the Bratsk mayor (i.e. the candidate supported by the governor), the candidates are viciously attacking each other in the media, and so on. In other words, there is a potential for conflict even among the elites. And when an opportunity arises, it is immediately exploited, and elections begin to do what they were originally designed to do: to help resolve this inter-elite conflict in a public and civilized way.

In this case, it is not worth looking at the party affiliation of the candidates: the party system at the local level in Russia is practically non-existent, parties are simply used by elites as «licenses» to participate in electoral politics (another example from the Irkutsk region is illustrative: the former head of the Taishet district, who left the «United Russia» party for the second time in his political career, is running for mayor as a self-nominated candidate, whereas before he was a CPRF candidate). Thus, it is the level of local self-government that today has the greatest potential for the rapid revival of real elections, political discussion and competition, because here the public political struggle is still alive.