Social media are becoming as commonly used as the Internet itself. Today, it seems almost ridiculous to claim that the digitalisation of society is synonymous with liberalisation and that unrestricted access to information gives citizens control over the authorities and corporations. As it turns out, anonymous online whistle-blowing and cross border instant communications have not curtailed political scheming or managed to channel public pressure into anything unambiguously constructive. Instead, it just allows for more grey zones for political and financial scheming. In addition, users often need to hide their views in order not to fall victim to online trolling or not to lose their virtual social capital.

This leads to the emergence of closed circles of communication and walled ecosystems. Using the example of the American alt-right movement, we can observe how bloggers, news sites and forums evolve into complex hierarchical systems, taking users out of the influence of mainstream media. The effect of this “echo chamber” opens the door for the most incredible rumours, delusional accusations and other news driven by either delusional hopes or human fears. Users of online sites find it much easier to exclude an interlocutor from their private communication space by blocking them. As a result, the problem of fake news requires top-down activism from the highest level: the U.S. Congress has held hearings, and Mark Zuckerberg has been forced to apologise to Facebook users, vowing to make changes to his company’s political advertising rules. Twitter is considering similar steps.

The dubious quality of information disseminated via social media is not just an American problem. Let us try and identify several factors that may contribute to, or hinder, the creation of ideological ecosystems in social media in Russia.

An environment ripe for Fake News

First of all, let us turn to the statistics regarding social media users in Russia. Social media sites are used by 60% of Russians today, and by 86% of all those who use the Internet. Undoubtedly, the use of social media is very much a routine practice if we are talking about young and middle-aged people. At the same time, the intensity of social media usage is varied: young Russians mostly use them every day; middle-aged respondents use them regularly (several times a week/month); older age groups tend to steer well clear: Only a minority uses the Internet. Over the past five years, we have not observed any significant increase in social media usage, which may indicate that this space has become saturated. Most likely, further penetration of social media will proceed slowly, as new generations gradually come of age. Nevertheless, the existing audience is already easily large enough to explore mass phenomena occuring within it.

It seems that political pluralism is another necessary condition for the emergence of powerful political movements within social media. We should also consider why the ‘alternative’ forces that emerge in the West often have an ultra-right dimension. Discontent among part of the population is fuelled by an underlying fear of globalised, rapidly changing societies: the fear of becoming a marginalised minority and of losing hope for the future. This intensifying polarisation is in turn reflected in the growing number of members of parliament elected from right-wing parties across much of Europe and North America. They strengthen their influences by using the widespread fear of migration, globalisation and economic stratification as regular talking points, often in a manner that is blunt and therefore shocking and shareable. In today’s Russia, the risk of the emergence of populist parties is minimised by the very design of the political system, where the adversarial principle in politics is minimized. If discontent seeped into Russia’s own institutions or party politics, it could accelerate the emergence of new populists. There is certainly a social foundation for this: nationalists and ‘left-wing statehood supporters’ enjoyed broad support in the 1990s, and yet the key problems have remained unchanged: i.e. the low living standard of ordinary Russians and general feelings of uncertainty about the future.

Social Media as a source of news

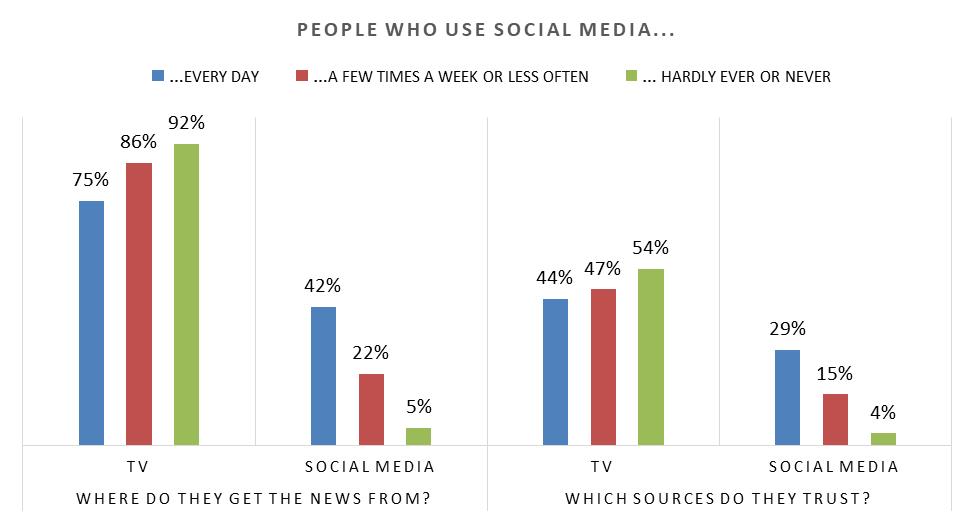

Quite logically, ideological subcultures similar to alt-right structures in the USA and Europe will be formed by users who trust information from the new media rather than traditional news sources. Data from all-Russian polls conducted by the Levada Center suggest that more active social media users are more likely to absorb their news online and, at the same time, have more trust in news obtained in social media.

However, we face two hypothetical difficulties here. Firstly, the daily use of social media is already a mass phenomenon, and has not — at least so far — been a sufficient factor to drive the emergence of alternate political ecosystems. Up to 90% of those who use social media for several hours a day get their news from there, whereas TV news remains an important source for only a half of that group.

Secondly, survey data indicate a general trend: social media are viewed by most users as a continuation of their own private space rather than a ‘public’ sphere which should offer space for political discussions. An absolute minority of social media users would like to see more news from social media (5%) while 67% want to see messages from their friends and relatives more often.

The idea of introducing an identification procedure for news portals seems an obvious but an insufficient step. Viral information is often shared among friends, acquiring special significance and a certain ‘seal of trust’: after all, we trust our friends and relatives more than various kinds of mass media organisations. The ‘second circle’ of acquaintances may become an even less verifiable source of information. This circle includes those whom the users do not know personally, but whose opinions they consider: 24% of social media users would like to see messages from people who share similar views but are not personal friends. Such sources might be fully involved in “meaningful interactions” mentioned by Mark Zuckerberg when he announced changes in news feeding algorithms, and yet it is virtually impossible to confirm the reliability of such information if it is not distributed via bots.

Interaction with contradictory news

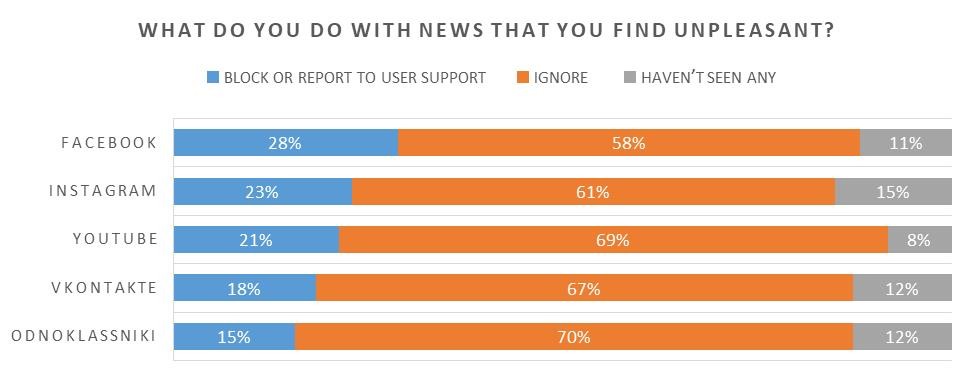

Subjective assessment of news remains the most significant reason for spreading fake news. Any social media use will sooner or later be confronted with fake news or with content that does not correspond to their own ideas of what is right and beautiful. At least a half of social media users admitted that they encountered unpleasant information at least from time to time. In this case, the difference between users of different media covered by our survey is insignificant. Facebook, Youtube and Twitter actively promote the blocking tool, thus creating a perfect environment for the emergence of echo-chambers. Interestingly, the architecture of Odnoklassniki and VKontakte promotes the communication with a circle of friends without encouraging the distribution of hyped-up news.

The model of user behaviour when encountering such news in non-Russian social media differs significantly from the model prevailing in Odnoklassniki or VKontakte. Facebook users are most likely to take action: 28% block such news or report it to user support. Users of VKontakte and Odnoklassniki are more ‘loyal’ (or indifferent) to what they consider unpleasant news.

Quite obviously, these differences stem not only from cultural but also legal differences as major media in Western countries must respond to new regulatory imperatives. In addition, less popular social media attract a more sophisticated audience, more concerned about its own ‘news feed hygiene’ and attaching more importance to their virtual space. Survey data clearly indicate that users of VKontakte and, especially, of Odnoklassniki are less interested in political news and are generally closer to the image of an average Russian citizen. At first glance, users of these Russian social networks are less inclined to create and spread sensational news outside their own circle, but are more likely to act as recipients of information. For this reason, the waves of viral content are more short-lived but also more powerful because of the larger size of the audience.

Today’s Russia does not have the breeding ground that could contribute to the emergence of ideological subcultures in the virtual space to the extent seen in the West. Despite the relatively high popularity of social media, the largest ones, i.e. VKontakte and Odnoklassniki, are used by about a half of the Russian population. However, those media are largely apolitical or state-dependent. The highest potential for the emergence of political movements is represented by Facebook (9%), Twitter (4%), Youtube (15%) and, possibly, Instagram (14%), all of which are much less popular. In addition, we do not see the necessary resources offline that is essential for the emergence of structured ecosystems. The state remains the only established political stronghold and it is capable of organising troll farms and repressing political statements in the news sources it controls.