In Russia’s domestic politics, the year 2023 will be marked by the presidential election campaign. While it formally starts in December, it has already begun informally: the Central Election Commission of Russia has announced the launch of preparations for the presidential elections. The electoral event itself will take place in March 2024 unless something unexpected happens.

However, 2023 will abound in insights about the situation among the authorities and in society. Also, this year will certainly witness some electoral wheeling and dealing. September will see the biggest regional election campaign in the five-year political cycle. In autumn, a total of 18 heads of regions, members of 16 regional parliaments and 12 town councils as well as the mayor of Khabarovsk (the seized territories are not counted here) will be elected in a direct vote. Approximately 53.5 million people, i.e. a half of all voters in the country, will be able go to the polls in these elections. In addition, several thousand small-scale local government elections will be held.

The main intrigue

The first major elections after the start of full-scale hostilities in Ukraine were the 2022 Single Voting Day campaigns. However, as noted by experts, these events were not very informative: this set of campaigns was too convenient for the authorities and there were relatively few of them. This means that the 2023 elections will offer the first real test of the authorities’ electoral capabilities since the start of the invasion.

What makes this electoral season particularly intriguing is that the set of campaigns is much the same as in 2018, when the campaigns caused so much trouble for the Kremlin. Five years ago, the authorities’ ratings were low because the increased retirement age had been announced shortly before the elections. This led to sensational defeats of administration-backed candidates in governor elections in four regions: Khakassia, Primorsky Krai, Khabarovsk Krai and the Vladimir Region. If we consider the protagonists in those elections, only the young Communist Valentin Konovalov from Khakassia remained the head of the region. On 2 February 2023, the former governor of the Khabarovsk Krai, Sergey Furgal, was found guilty on charges of murder and attempted murder. The former governor of the Vladimir Region advanced to the position of a member of parliament (MP) in the State Duma in 2021. Andrey Ishchenko, who was barred from winning the Primorsky Krai governor election, is awaiting a sentence in a pre-trial detention facility in a fraud case. However, the crushing defeat of the Primorsky branch of the Communist Party (CPRF), whose leader, Artem Samsonov, was also sent to prison, is not very helpful to Oleg Kozhemyako, the acting governor, who is struggling to manage conflicts among local elites. For example, in December 2022, he failed to push his protégé for the position of the head of a region.

This year is also likely to bring a large number of election campaigns that will turn out difficult for the Kremlin: if they cannot reveal the real political preferences of Russian voters, then at least they can tell how much control over regional and local elections the federal authorities have retained today.

Which elections to follow?

One of the main election campaigns this year is the one for the mayor of Moscow. The incumbent Sergey Sobyanin is unlikely to face any serious competition, but since this is the biggest election of the year, it will certainly attract a lot of attention (with over 7 million voters in Moscow and hosts of Russian and international journalists). It is also a great way to offer some promotion to a presidential candidate, even though the election will officially start about three months after the Single Voting Day. This applies in particular to the New People: the party has made it to the parliament, but the visibility of its top leaders is still rather low.

We have already mentioned Khakassia, where Communist Valentin Konovalov should try to retain his post. His is likely to be challenged by Sergey Sokol, member of the State Duma, former speaker of the Irkutsk legislature and former deputy governor of the Irkutsk Region and Krasnoyarsk Krai, who has also managed to work in ROSTEC structures as an adviser to Sergey Chemezov. Sergey Sokol has been in the war zone since October as part of the BARS Kaskad unit, which, besides him, allegedly includes other MPs from the State Duma and regional legislative assemblies. It is meaningful that Sergey Kiriyenko, deputy head of Russia’s presidential administration in charge of domestic policy, visited the unit during Christmas. Therefore, BARS Kaskad should perhaps be considered as a potential source of personnel for the Russian authorities. The situation in Khakassia is complicated by the fact that three major election campaigns will be held there at once: in addition to the head of the republic, voters will elect regional MPs and the Abakan City Duma.

In Yakutia, much like in Khakassia, also three elections are to be held: for the head of the republic, as well as the republican and city legislatures. Yakutia is a distinctive region, one reason being that Sardana Avksentyeva, now a State Duma member and one of the leaders of New People, won the elections and became a mayor. In general, the New People party can be seen as one of the riddles in the campaign because they are the only party in the State Duma without a governor among its members.

Governor elections will also be held in Primorsky Krai and although Oleg Kozhemyako managed to practically destroy one of the strongest Communist Party branches in the country, he cannot feel at ease given his negative rating and proneness to engage in conflicts. Also, a troubled situation with conflicts among the elites is emerging in the Novosibirsk Region, where Andrey Travnikov, a rather weak governor, is likely to retain his position. However, in the same region, the head of Novosibirsk, Communist Anatoly Lokot, has already been elected twice in direct elections. Right now, the region is fighting to abolish direct elections for the post of the mayor of the country’s largest municipality.

The mayoral elections in Khabarovsk should reveal how much influence Sergey Furgal’s team has maintained in the region. Important elections to local government bodies will also take place in Yekaterinburg, one of the democratic capitals of Russia, and in Novgorod, where the regional branch of Yabloko, which has been actively speaking out against the war, will try to keep its faction.

Elections to the regional parliament are also coming up in Zabaykalye (Transbaikal Territory). Last time, the results were very interesting: United Russia, the Liberal Democrats and the Communists got almost the same numbers of votes. A similar conundrum is expected in the Ulyanovsk Region, where the Communists got more votes in 2018 than the ‘party of power’, and in the Nenets Autonomous District, where United Russia got less than 39% in that year. Regional MPs will also be elected in some of Russia’s most opposition-minded administrative units, i.e. Irkutsk and Yaroslavl Regions.

Big elections are also going to take place in two regions with serious environmental issues: in Krasnoyarsk, the people will elect the city legislature, whereas the voters in Arkhangelsk Region will elect regional MPs in addition to the city legislature.

How are the authorities preparing for the elections?

A number of legislative innovations will distinguish this year’s elections from the 2018 efforts. In particular, this is likely to be the first campaign in history where remote electronic voting (DEG) technology (i.e. online voting) will be piloted on a large scale. The scandals that affected the Moscow DEG system should not be counted here, since Moscow uses its own DEG rather than the federal one in regional and local elections: actually, the federal system is being prepared for the presidential campaign. So far, the federal DEG has only been used in a handful of regions and on a small scale.

The system is extremely non-transparent: there are no real tools for citizens or candidates to monitor it. However, as the Moscow experience shows, the active use of the system in the upcoming September elections can seriously undermine citizens’ confidence. Election organisers are unlikely to take such risks on the eve of the presidential campaign, which they see as more important.

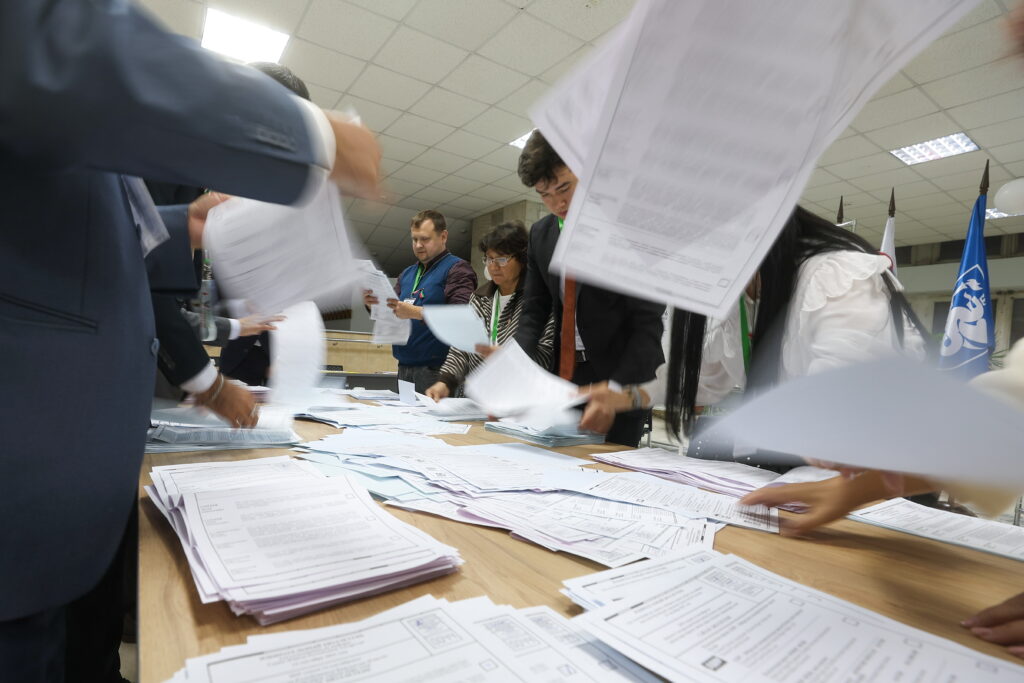

Another aspect is that the status of non-voting commission member, which had been actively used for election monitoring by candidates, parties and public associations, was abolished last year. As a result, opportunities for public scrutiny of the fairness of the voting and vote-counting procedures will be significantly more limited than five years ago.

Despite all that, the authorities are showing uncertainty about the outcome and are trying to change the electoral rules. The ten-year term of the former constituency boundaries expired at the beginning of this year, and we are now seeing an active process of boundary ‘re-cutting’ in the best traditions of gerrymandering: protesting districts are being divided and diluted as more loyal electorate is added. This often means that a district will be stretched thinly across the city or that rural voters will be added to urban ones.

The second innovation, which will have a significant impact on the final distribution of mandates, is that the proportion of MPs elected from party lists is being actively reduced, in favour of the majoritarian electoral system. This has already happened in the Yaroslavl and Ivanovo Regions.

In regions which are preparing for gubernatorial elections, a traditional battle is unfolding over the size of the ‘municipal filter’, i.e. the number of signatures that a gubernatorial candidate must collect from of municipal heads and MPs. In the vast majority of regions, this number is so high that no party except United Russia has enough MPs and heads of local government to reach it. In late January, an attempt by the CPRF to lower the ‘municipal filter’ failed by a thin margin in the Altai Krai: it was barely five votes short of being passed. In Primorsky Krai, the authorities were able to make life even more difficult for potential candidates by significantly raising one of the filtering parameters.

All this seems to suggest that there is some uncertainty about the outcome among the informal organisers of the elections. A lot will depend on the actual voter turnout and the condition of the economy 1.5 years after the start of the war and sanctions. So far, the rule has been that the federal authorities started injecting budgetary funds and various development programmes into difficult regions during election years. However, the number of struggling regions is high, and their problems are clearly not in the foreground: instead, the budgetary funds are required for conducting military operations and keeping the economy afloat. The authorities’ thoughts are far away from goals such as urban improvements, massive road repairs or welfare spending.

For example, the Yaroslavl region has already announced that social benefits will only be indexed at 5.9%, i.e. well below the official inflation rate of 12%. The authorities have even refused to subsidise school breakfasts (10 roubles per meal) and also want to cut the headcount of municipal officials by 30%. In rural areas, this often means that former municipal officials are directly sent to unemployment and end up in poverty, as there are simply no other jobs available. This casts a painful blow to the bureaucratic networks which are also responsible for elections, and forces their members to enter into direct conflicts with regional authorities.

Even the affluent Irkutsk region (among the Top 20 in terms of budgetary provision, and excluded from the list of subsidized regions in 2022) faces acute problems with the social services. In March 2022, the region recorded a shortage of about two thousand teachers in its schools, and in December classes in schools of one district were cancelled due to the unavailability of specialised teachers. Meanwhile, the shortage of medical doctors reached 38%.

Amidst the shock caused by the outbreak of hostilities, sanctions and mobilisation, voters may temporarily forget about these issues, but too much time will pass before September 2023, and the lingering problems will resurface and begin to play an important role again.