When we look back, it might seem that six years ago people in Russia lived in a different country: the residents of a small town of Saransk welcomed football players and fans from Europe, Asia, Africa and Latin America, while the residents of Khabarovsk Krai, Khakassia and Vladimir Region managed to elect their governors from outside the group of Kremlin’s favourites.

In reality, all these memories date back to the period after the 2018 presidential election. During the election campaign, the picture was more bleak: Vladimir Putin won with 77% of the vote, the «liberal» candidates Boris Titov, Ksenia Sobchak and Grigory Yavlinsky gained between 0.7% and 1.7%, and the pre-agreed candidate of the Communist Party of the Russian Federation Pavel Grudinin received so much pressure that he could not fully recover even after six years. According to various assessments, falsifications totalled between 12 and 17 million votes while voters themselves faced fierce coercion — there was no difference in pressure between public sector employees and those working in the commercial sector: the authorities succeeded in mobilising both.

From 77% for the incumbent, Russia then went to second rounds of governor elections in merely six months. The recipe for this rapid change is simple and consists of only two ingredients: unclenching the ‘spring of pressure’ that was too tight during the presidential election and implementing the unpopular pension reform. It has become a tradition to make unpopular decisions immediately after federal elections: the pension reform after the 2018 elections, and the war after the 2021 elections.

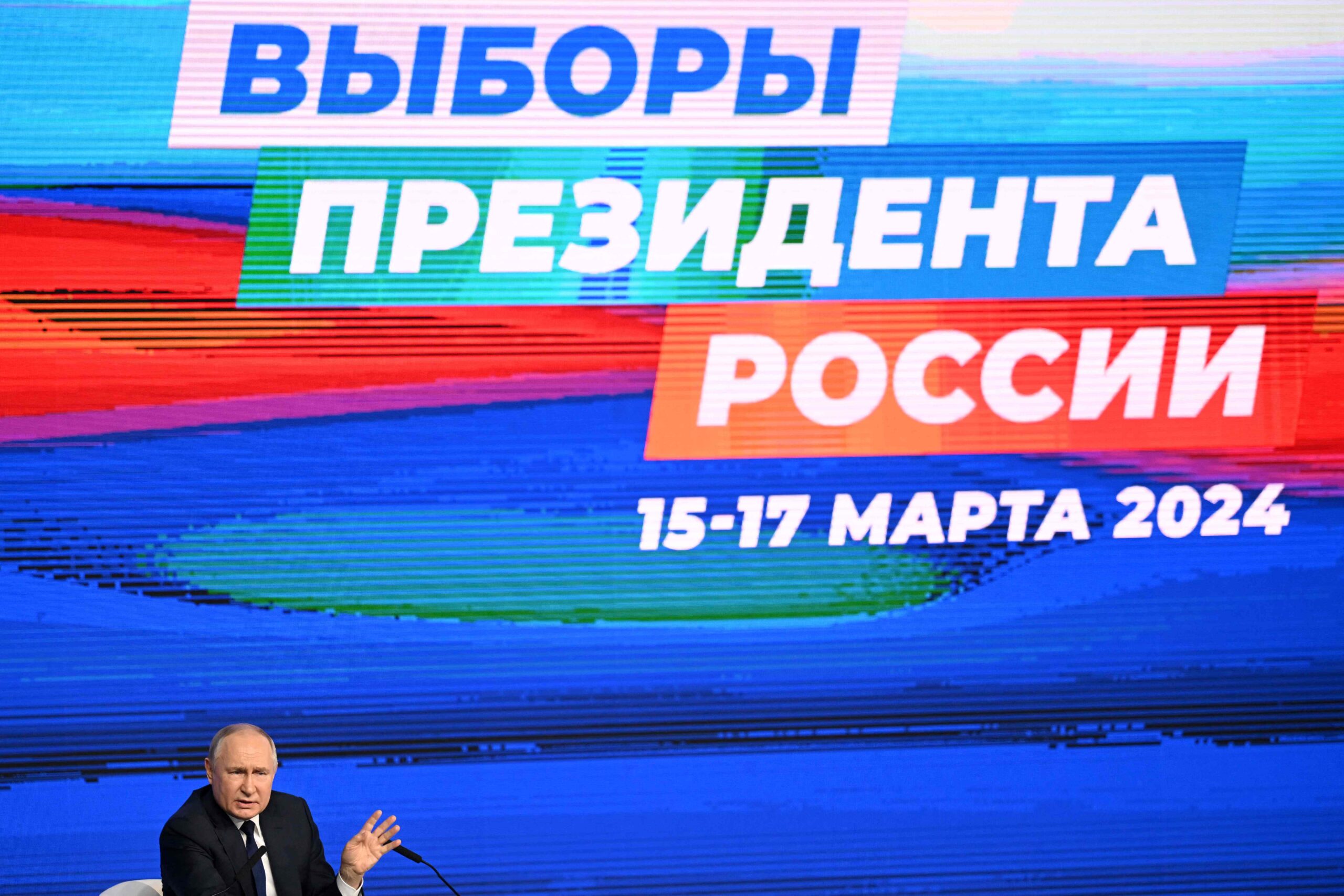

It is not completely clear what will happen after the 2024 elections, but there are many similarities with 2018. Firstly, housing and utility bills and, probably, prices on simple mass goods will rise dramatically. Secondly, the pressure on voters has already begun and is likely to be even stronger than six years ago. The media are leaking rumours about desirable target figures for voter turnout and support for the incumbent president: both should be higher than in 2018. At the same time, these figures can only be achieved with pressure because the election campaign is virtually non-existent: the amount of television airtime devoted to the elections has fallen 1.5 times, even in relation to those modest 2018 figures, and the candidates behave in a way that may save them from repeating the fate of Pavel Grudinin.

But what is the difference between the 2024 election and the 2018 election anyway?

A different political environment

Firstly, the country has a qualitatively different political environment in 2024: the war, war-related censorship and increased repression.

By the 2018 elections, the «Crimea effect» of 2014 was already over: in fact, it was no longer noticeable in the 2016 State Duma elections, either. Precisely for this reason, the Russian authorities, unexpectedly for themselves, had to pour «black PR» on Communist Pavel Grudinin in prime time: it turned out that the demand for new faces had already emerged at that time. The New People party utilised this demand in 2021, managing to get into the State Duma within less than 1.5 years after it was founded.

Society has been changing noticeably as well. According to the Levada Center, in October 2018, the fear of arbitrary governance and lawlessness broke into the Top 3 fears felt by Russians, while the fears of returning repression and a tougher political regime ranked sixth and seventh respectively. At the same time, the traditional social fear of poverty ranked fourth, the fear of loss of savings came ninth, while the fear of losing one’s job did not even make it into the Top 10.

Not surprisingly, the authorities felt insecure. This triggered, in particular, the amendments to the Constitution, which were designed to «fossilise» the existing regime. In 2020, there was an attempt to poison Alexey Navalny, followed by his arrest and the defeat of the regional network of his supporters, who were officially recognised as extremists.

The war probably was triggered, at least partly, by this growing conflict with society: during the pandemic, the authorities realised how much more comfortable they were in a state of emergency. The war was followed by military censorship, which blocked hundreds of media outlets and several social networks. The war was followed by a new wave of repression, the demobilisation of the most protest-minded electorate and the fear among politicians (even those tied with the system) who were afraid of participating in elections (the number of those wishing to become candidates in the 2023 elections hit a record-low level).

It would seem that the Russian authorities should feel very confident in these conditions in 2024: sociologists report on unprecedented unity of the nation, political rivals are either in jail or have fled the country, opposition media are blocked, system-bound politicians «toe the line,» trying not to show their ambitions in any way.

Nevertheless, preparations for the presidential election seemed rather frantic, which had a noticeable impact on the electoral legislation.

Other laws

The law «On the Election of the President of Russia» has changed a lot: 52 out of 87 articles and three out of its four annexes have been amended. In fact, this has already become a tradition since Russia has never held a major election under the same rules as the previous ones. However, the nature of the amendments introduced this time has attracted attention.

The key change is the adoption of amendments to the Russian Constitution that «nullified» the terms of office for the incumbent president. Indeed, this is an understandable and traditional story for autocracies: one can hardly find an old authoritarian regime that has never «nullified» presidential terms of office or otherwise prolonged the autocrat’s right to stay in power legally for as long as he wants.

Another thing that attracts attention is that most of the changes made to the legislation in 2018−2023 were aimed at limiting citizens’ electoral rights, reducing possibilities for public scrutiny and increasing opportunities for manipulation.

For example, the collection of signatures in support of the nomination of candidates was seriously hampered: the signature collection template was unified (for some reason, it must contain exactly five lines, no more and no less); a requirement was added for voters to handwrite not only their signature and the date of signing, but also the their full name, including the patronymic (this leads to an increased number of errors). What deserves particular attention is that the electoral legislation introduced a provision in 2020 allowing to collect signatures in support of candidate nominations via the Internet, using the Gosuslugi web portal. However, this legal provision was never implemented in the legislation on the presidential election in Russia, which is why a large number of voters who were outside their region were actually deprived of the opportunity to support the nomination of ‘their’ candidate.

The most active part opposition-minded voters, despite organisational resources and public awareness, were stripped of their electoral rights. This was facilitated by a significant amendment to the legislation on «foreign agents.» They are still allowed to run as candidates, but forbidden from participating «in the pursuit of activities that facilitate or hinder the preparation and conduct of the election of the President of the Russian Federation, nomination, registration and election of a candidate, and, moreover, participation in the election campaign in other forms is not allowed.» It is separately stipulated that «foreign agents» cannot be members of electoral commissions or act as donors for candidates.

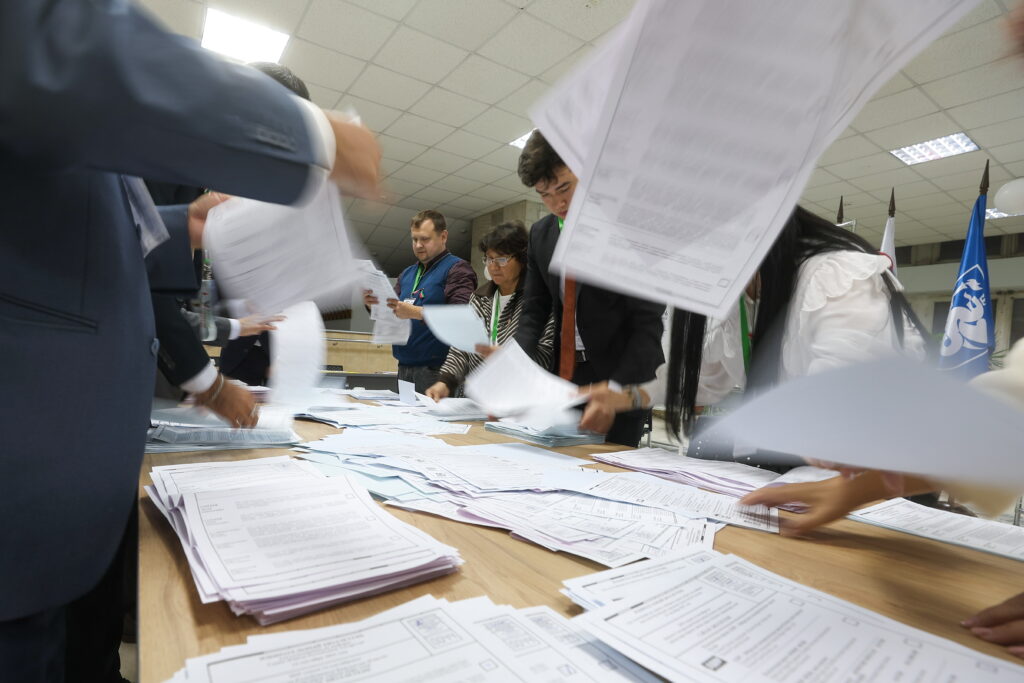

The options for monitoring the voting results have been restricted to a maximum extent. Firstly, the institute of members of election commissions with a consultative capacity was virtually abolished: they remained in regional-level election commissions and in the Central Electoral Commission (CEC) of Russia, but with reduced powers. Secondly, the legislators decided to interfere in the work of editorial offices of various media and stipulated that only journalists with fully-fledged work contracts could receive accreditation at polling stations whereas freelancers working for the media were deprived of this possibility. Finally, the changes have also affected the institute of electoral observers: a requirement was added to submit the list of observers to the Territorial Election Commissions no later than three days before election day. Such requirement had not been previously included in the law «On the Election of the President of Russia.» After yet another restriction that has been introduced, the voting premises must have places allocated for observers and media representatives, based on the requirements established by the CEC. This, in fact, restricts the observers’ freedom of choosing the place of observation in the specific situation that may occur.

Of course, what has seriously undermined the reliability of election results is the possibility of stretching the voting process over three days and the addition of completely uncontrolled online voting option (the latter, however, will not apply on the entire territory of the country, but only in 29 regions, inhabited by approx. 38 million voters).

In essence, the authorities have demonstrated that in the current circumstances they are not sure if citizens’ support is real. There are reasons underlying these concerns, including the public reaction to the military mutiny in June 2023, the speeches by the wives of mobilised men, the attempted pogrom of Jews in Dagestan, and the current events in Bashkortostan. There are sparks of tension in different parts of the country and in different segments of society, including those that were expected to be loyal. So far, the authorities have prevented these hotbeds from organising themselves, but there is clearly a lot of nervousness.

The flow of the campaign (or rather, the absence of any trace of it) suggests that the incumbent president will likely be re-elected in March with ease. However, this will require enormous pressure on society: with the current very modest campaign, the desired turnout figures and voting results can only be achieved through very strong administrative pressure on voters.

The problem for the authorities is that, as discussed above, this ‘compression of the spring’ will cause it to unclench after the election, as was the case in 2018.

Thus, the most interesting developments will begin after 17 March 2024.