The US Treasury Department’s announcement that it has designated Rosneft and Lukoil under an existing executive decree has prompted rounds of speculation about the economic damage to Russia. As of now, any foreign financial institution facilitating transactions with either company is exposed to secondary sanctions risks, cutting off its access to US banks and dollars. This is the first time the Trump administration has meaningfully expanded sanctions, even as the cohesion and coordination of sanctions efforts across the US government have atrophied from staff cuts and competing interests among officials. Puzzling over Trump’s personal beliefs is, at this point, a useless exercise. Most relevant is that his own statements make it appear as though he was forced into this by Moscow’s brilliant decision to blow up a potential Trump-Putin summit in Budapest. The timing of the decision is what stands out most.

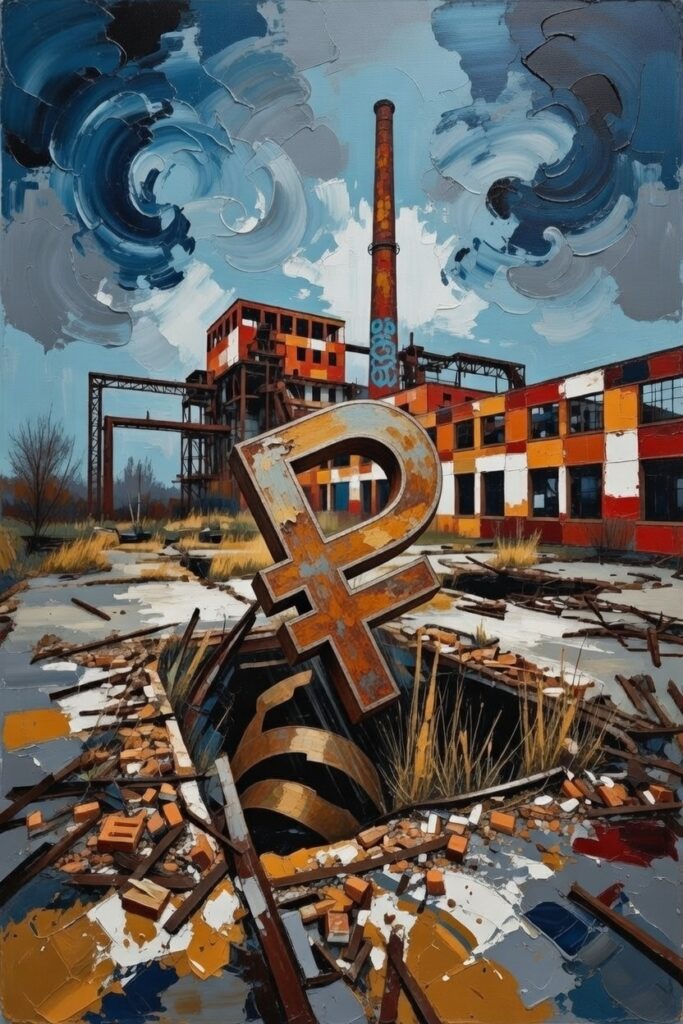

Energy sanctions have a mixed track record. Markets will always find a way to source barrels of oil. The threat of secondary sanctions on anyone transacting with Rosneft and Lukoil—Russia’s two largest oil producers—appears significant at first glance. China’s state oil firms are pausing purchases of seaborne volumes of Russian crude. Were the budget to lose out on revenues from these exports, the Ministry of Finance’s parlor games keeping the war going would become ever more difficult. Anton Siluanov has promised to uplift pension benefits, maternity capital payments, and state wages. The greater increases in construction costs and persistent need to max out war spending will take yet more money away from capital investments into infrastructure, the absence of which is squeezing what few pockets of non-military economic growth are left. German Gref and Sber are forecasting 0.8% GDP growth this year. Moreover, he has openly challenged increasingly insular labor policies, admitting that without 2.8 to 5 million qualified migrants, future growth won’t return to a half-decent pace.

Oil market balances explain both Trump’s willingness to follow through with oil sanctions and the subtle shell game taking place over their intent. After months of increasing OPEC output and an increasingly mixed demand picture—China’s stockpiling hundreds of thousands of barrels every day has lifted demand growth this year—going after Russian oil exports was safe. US officials have latitude to pressure Saudi Arabia to keep increasing production while offering to do their part in removing Russian barrels from the market. But as a practical matter, sanctioning oil companies instead of oil exports themselves will allow for the creation of unsanctioned entities to mask transactions. Unless the administration has rediscovered an appreciation for the value of efficient bureaucracy—a virtually impossible position given the current political environment—enforcement will eventually atrophy in the months ahead.

However, the mere threat of secondary sanctions may contribute to a greater discount on Russian exports as a condition for buyers taking the risks associated with Rosneft and Lukoil. Even more importantly, these sanctions may imply a greater willingness to support Ukrainian strikes on assets owned by both companies beyond refineries. The transfer of authorizations for strikes using US kit from the Pentagon to EUCOM suggests a more aggressive posture from Washington on that front. As such, these sanctions aren’t intended to stop Russian supply or the 3.1 million barrels of exports by Rosneft and Lukoil from coming to market. They’re a tightening of the noose to give the attempted price cap teeth and drive up Russia’s budget deficit while doing enough to prop prices up at or above $ 60 during a period of sustained oversupply—a gift to US oil and gas firms who would struggle if oil prices fell below $ 60 for an extended period.

Inflation is the unresolved challenge within Russia that is now strangling productivity and investment while chipping away at living standards. Ukraine’s campaign of strikes against refineries and associated fuel shortages have helped drive headline inflation back toward growth, now at 8.14% for the year. But where high inflation in 2023−2024 could be linked to rising output or demand, that’s no longer the case outside of the military. In 25 out of 28 regions with the largest housing markets surveyed by RBK, demand for new-build homes has fallen year-on-year, often more than 25%. Kaliningrad and Nizhny Novgorod were the only ones posting growth. Industrial investment plans are at 3-year lows and turning into layoffs due to a lack of consumer demand, while rail deliveries are down 6.7% year-on-year. But a hit to energy revenues will drive up federal deficits, which in a supply-constrained economy will drive up inflation. The higher inflation sticks, the longer the Bank of Russia must hold interest rates high, fending off demands from the presidential administration or cabinet even as oil markets find ways of buying Russian crude.

From an oil market perspective, 2026 will likely be worse than 2025. The US economy can’t float on the AI bubble forever, which is propping up US fuel demand somewhat. Battery or plug-in electric vehicles already account for over half of all vehicle sales in China, and global sales growth was up 26% year-on-year, reaching 14.7 million units for January-September. At the current pace, the world’s emerging markets—once believed to provide a cushion for future oil demand—will buy more electric vehicles than in North America every month by early next year. And that’s before addressing the beginnings of an expansion of battery-powered trucks emanating from China or the availability of supply that caps price upside.

Moscow is caught between a rock and a hard place. Its most important economic partner, China, continues to accelerate the adoption of electric vehicles both at home and globally through exports. Meanwhile, the United States is attempting to keep oil prices low enough to help tame inflation that is now endemic due to tariffs and other policies, and just high enough to avoid a wipeout among domestic producers.

The trouble with recent tax hikes like the VAT increase to 22% is that they largely rely on the labor market to deliver. We’re finally seeing signs of a pullback in the number of vacancies, though the economy maintains a huge labor deficit. Industrial production as a whole has stagnated for over a year now, likely in part due to a lack of labor to make things. Prime Minister Mishustin and the government keep insisting real incomes are growing—4.5% this year!—but these figures are unbelievable in light of where cost increases have taken place in relation to the average Russian’s consumption basket. One survey from the Public Opinion Fund found just 8% of respondents said that their material situation had improved in the last 2−3 months, and Sber’s consumer spending index posted its historically worst performance: a 1.3% inflation-adjusted decline in consumer spending that masks a further real-terms decrease in the physical turnover of goods.

Now is an ideal time to hit Rosneft and Lukoil because the damage on the oil market would be contained and the net effect would likely drive up the deficit and inflation next year. We’re not yet at a point where the regime’s war machine is breaking down. But the volumes of sand being thrown into the gears are taking a toll. TsMAKP’s industrial review for Q3 shows that the regime can only defy gravity for so long. The Higher School of Economics’ aggregated index shows net industrial production is just 1.3% higher than it was in January 2023. The attacks on Ukrainian infrastructure will continue, if only because there is no feasible way to increase the intensity directly at the front. Next comes the bigger question from the sanctions: will Ukraine be unleashed to pursue greater strikes on key targets?