On May 14, searches were conducted at Russia’s largest publishing house, Eksmo, and its subsidiaries, Individuum and Popcorn Books, as part of a case involving «LGBT propaganda.» On May 15, managers from Individuum and Popcorn Books were placed under house arrest. The likely trigger was the book Summer in a Pioneer Tie, about a relationship between a pioneer and a counselor, which drew criticism from State Duma deputies and Ekaterina Mizulina, head of the Safe Internet League. According to the BBC, other books not directly criticized by conservatives are also involved in the case and remain on sale.

The searches and arrests at Eksmo are the most prominent evidence of state-enforced censorship entering the book publishing market. These events follow less high-profile instances of pressure on the book industry: security forces visited Moscow’s popular Falanster bookstore, and an administrative case was opened against its co-founder, Boris Kupriyanov, for activities related to an «undesirable organization.» Authorities also visited St. Petersburg’s well-known Podpisnye Izdaniya bookstore and other bookshops across Russia.

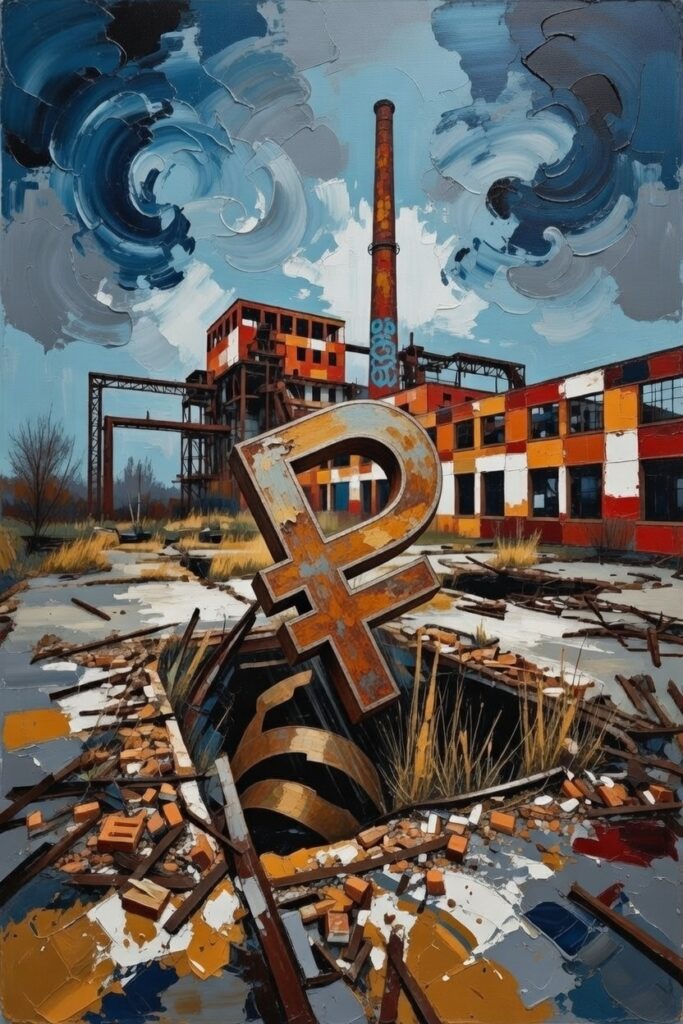

Since the start of the full-scale war, publishers operated relatively calmly, with clear red lines for censorship and self-censorship. Criticism of the government, the war, and later LGBT themes were off-limits. Publishers found an outlet in high-quality educational books and fiction, rediscovering Eastern novels and comics after losing rights to some Western releases. The book market became part of the cultural phenomenon of the «new quiet ones”—writers, musicians, directors, actors, publishers, and artists who avoided sensitive social issues while not openly supporting the war or regime. These «new quiet ones» helped Russians opposed to the war escape reality, serving a psychotherapeutic role and reducing anxiety. Bookstores, publishers, and fairs became cultural hubs and, amid censorship in music and theater, a last «quiet haven.»

The state’s intrusion into this haven was only a matter of time. Pro-war writers complained about low book sales, blaming publishers and bookstores. Ultrapatriotic politicians demanded priority for pro-war literature. Under such pressure, cultural overseers in the government and Kremlin typically yield, as no official wants to be labeled a freethinker and risk their position. The system of denunciations, already tested in the concert industry, is now spreading to the book market.

The case against Eksmo managers and the transfer of the book industry under the Ministry of Culture signal the end of the «new quiet ones» in Russian culture. Ultrapatriots, including the country’s top leadership and President Vladimir Putin, are no longer satisfied with «silence.» They demand active support, with criminal penalties—such as for «propaganda» of LGBT issues or drugs (where any non-critical mention can be deemed propaganda) or for criticizing the government or war—prepared for dissenters.

Communicators Instead of a «New Elite»

The Kremlin’s political bloc continues its PR project, «New Elite.» RBC reports that regions have received new KPIs for training war veterans in local programs for military personnel. Such courses exist in most Russian regions, with targets ranging from 30 to 60 participants. Graduates are recommended for roles in local administrations as «communicators» to help officials better engage with war participants.

«If veterans have questions for the authorities and a regular official responds, they might dismiss them, saying, ‘Who are you? You haven’t fought.’ We need people who command respect and can speak as equals,» an Administration official told RBC.

However, a veteran with grievances against local, regional, or national leadership is unlikely to respect an official just because they also fought. Many are aware of «deputy» and «official» battalions, and they may not distinguish between genuine veterans and officials claiming frontline experience. The KPIs are modest—for instance, Primorsky Krai’s governor, Oleg Kozhemyako, said 60,000 from his region are fighting. Even at the highest Kremlin target, only about one in a thousand veterans would be trained, with even fewer securing posts. No mass influx of veterans into «communicator» roles is expected. Yet, the Kremlin’s political managers will likely report low-level appointments in federal media to create the impression of continuous veteran promotions, symbolically inflating the scope of these decisions.

For the first time, the Presidential Administration has cautiously outlined veterans’ future role in the power structure. Putin has repeatedly said veterans should become the «new elite,» replacing the old. However, the «communicator» role suggests they will mediate between traditional elites and returning veterans, not join or replace the elite. This signal reassures current officials and deputies that they won’t be replaced, only given assistants to handle potential crises.

The narrative of veteran appointments primarily targets Putin, who expects the rise of a «new elite.» The appointment of Igor Yurgin, a war veteran and former Yakutia youth minister, as head of the Education Ministry’s youth policy department fits this narrative. However, such roles have vague authority and limited budgets, which are key to influence in the power vertical.

Promoting veterans remains the Kremlin’s main PR strategy. It aligns with Putin’s vision while reassuring the old elite by framing veterans as communicators. The buzz around veterans generates constant news—new KPIs, low-level appointments, or statements by appointees. This artificial strategy (no mass veteran advancement exists) is foolproof, with no measurable KPIs for effectiveness, ensuring no perceived failures. Kremlin managers will continue leveraging it.

The Second Party

On May 14, Russian officials discussed celebrating the 80th anniversary of the late LDPR founder Vladimir Zhirinovsky. Attendees included State Duma Speaker Vyacheslav Volodin, Deputy Prime Minister Dmitry Chernyshenko, Culture Minister Olga Lyubimova, Education Minister Valery Falkov, Schools Minister Sergey Kravtsov, Finance Minister Anton Siluanov, Transport Minister Roman Starovoit, and Kremlin officials. Putin signed the celebration decree last year, likely at the political bloc’s urging. Nationwide festivities for a deceased, eccentric leader of a systemic opposition party seem odd but align with the Kremlin’s goal to make LDPR Russia’s second-most popular party. Under Leonid Slutsky, LDPR is fully dependent on Kremlin managers, fitting the role of «systemic opposition.» Even under Zhirinovsky, LDPR lacked a clear ideology, with the leader inconsistently advocating for or against policies like direct elections or migration. Today, LDPR’s themes—migration criticism or war support—are no longer unique, shared by parties like United Russia or A Just Russia. The ideologically rigid Communist Party, with its loyal base, is less manageable for the Kremlin.

Zhirinovsky’s anniversary celebrations are effectively an early, state-funded LDPR election campaign. His image remains the party’s key asset, as Slutsky lacks charisma, and absolute Kremlin loyalty doesn’t attract new voters (loyalists have United Russia). Events are planned in Moscow and regions, including schools, universities, and cultural centers. Moscow’s metro and Russian Railways will feature Zhirinovsky-named trains. This campaign could secure LDPR second place in elections or legitimize such a result, answering why a party without clear ideology or strong leaders ranked high: «LDPR and Zhirinovsky were everywhere, backed by authorities.»

This campaign is novel, but if successful, the Kremlin’s political bloc may replicate it to boost other «systemic opposition» parties.