he Moscow mayoral elections of 2017 were a great success for the opposition, and the next elections for the Moscow municipal councils are to be held in September 2022. What do we know about local politics in the city’s districts and what are the specificities of Muscovites’ political activity?

Dissatisfied Muscovites

Observation of Moscow political life indicates that a significant part of Muscovites are critical of the current political direction and are willing to actively express their preferences through protests and during elections. It is therefore crucial to understand which factors influence the civil and political behaviour of Muscovites.

The municipal elections in Moscow in 2017 aroused a level of interest that is unusual for this type of election, presumably due to the unexpected results, which brought about a decrease in the representation of deputies from United Russia and other parliamentary parties such as the Communist Party, the Liberal Democratic Party, A Just Russia, and a significant increase in the representation of deputies from Yabloko. Elections were held in almost all Moscow districts and 1,500 deputy mandates were distributed in municipalities. According to the results of these elections, the ruling party retained 1,153 deputies. The Communist Party suffered heavy losses of 159 seats, A Just Russia obtained 114 and the Liberal Democratic Party 21. The largest victory was achieved by Dmitry Gudkov and Maxim Katz of the Yabloko party, which saw an additional 152 mandates added to its representation.

In 2019, during the elections to the Moscow City Duma (MCD) — effectively a regional parliament as Moscow is one of three federal cities — there was a large-scale protest as residents expressed dissatisfaction with the barring of well-known opposition politicians. The rallies were brutally dispersed, and the results of the elections were announced as a success both by the party in power and by the opposition. The results of these elections were strikingly contradictory: Mayor Sergei Sobyanin retained control of the representative body and other candidates from the mayor’s office gained the majority in the MCD with 25 out of 45 mandates in total. Yet in comparison with the previous composition of the city Duma, the opposition significantly strengthened its representation: the Communist Party gained an additional eight mandates, Yabloko added four (and after the by-elections of 2021, the mandate of Yabloko’s Vladimir Ryzhkov was added) and A Just Russia three. Opposition candidates, according to a study by Mikhail Turchenko and Grigory Golosov, received an increase in votes of 5−7% due to the support of Smart Voting. It is worth noting that formally, United Russia did not participate in these elections: the candidates from the mayor’s office were self-nominated, and formed the ‘My Moscow’ deputy group in the MCD. In some districts, administrative candidates were nominated from the Communist Party, A Just Russia or Yabloko.

The results of the State Duma elections in 2021 in single-mandate districts in Moscow also showed the complex structure of Moscow politics and the critical mood of Muscovites: before the publication of the results of electronic voting, candidates supported by «smart voting» were in the lead in most districts.

The regional diversity of Moscow

Moscow as a federal subject consists of 125 municipalities and districts. Representative authorities in Moscow — the municipal councils — are formed through direct elections in several multi-member districts. Elections in all districts are held over one year, with the exception of the Shchukino district, where the municipal council is formed a year earlier than in others. The head of the municipality is elected from among the deputies. The executive power at the local level is detained by the councils, which are formed by the Government of Moscow. This board is accountable to the Government, but is also controlled by the municipal council although the powers of the council are, of course, very limited.

The last municipal elections in Moscow have been consistent with previous voting trends in the city: the central districts, some districts of the Northwest and Southwest are more disapproving and oppositional, while the southern and eastern districts are more likely to be loyal and vote for United Russia. According to the results of the 2017 municipal elections, the Gagarinsky district stands apart, where all seats were taken by candidates from Yabloko and a well-known activist and politician Elena Rusakova was elected head of the district.

What is behind the diversity in voting trends in Moscow and is there any reason to distinguish different district communities? Moscow districts differ in structural socio-economic characteristics, social relations that are formed within district communities, and the urban environment itself. The research project ‘Moscow mechanics’, organised by the Moscow Institute of Socio-Cultural Programs, studied the public opinion of Muscovites on key areas of urban life and their contributions to the state of the urban environment from 2013 to 2015. This large-scale research project produced several clusters of districts that unite according to similarity of values and practices and expectations of local residents in relation to the urban environment: Comfortable Moscow, Family Territories, Neighbouring Territories, Excluded Territories, etc. It is significant that ‘Mechanics of Moscow’ has uncovered a complex relationship between the social characteristics of district residents and the quality of the urban environment. The infrastructural self-sufficiency of some districts may be connected with social adversity, while the availability of cultural or educational institutions may be linked to dissatisfaction with their quality and expressed in a request for public participation to improve them.

Studies of Moscow renovation also point to territorial differences in the reaction of Muscovites to this programme. It is impossible not to interpret the renovation itself as political, not because it allowed to punish disloyal citizens by including their houses in the renovation, and to encourage loyal ones by not including them in the programme (or vice versa), but rather because of deeper political consequences. Regina Smith notes that if the renovation was conceived as a «political project», then there are many questions about its effectiveness. At first Muscovites seemed to unite against the government, but soon divides emerged. The renovation also allowed the government to test large-scale and unpopular reforms while minimising damage to regime stability. The government first announced a full plan, which included elements for a partial rollback, and after mass mobilisation the planned concessions were made. A similar mode of operation was observed during the protests against the raising of the retirement age.

Communication and collective action

Sociologist Anna Zhelnina notes that civil activists are increasingly politicised and manifest political ambitions as well as participating more actively in non-political civil action. The origins of this politicisation is found in the protests of the movement «For Fair Elections». But this trend has been greatly replenished as a result of anti-innovation mobilisation. Yana Gorokhovskaya showed how the coordination of the opposition and the political mobilisation of Muscovites differed in 2012 and 2017 (the years of municipal elections in Moscow). Her research demonstrated that participants of the 2011−2012 protests fell into various categories of political participation, and that the non-systemic opposition was increasingly professional in the conduct of election campaigns.

Research by Leonid Polishchuk and colleagues shows that Muscovites, like Russians in general, are willing to get involved in collective initiatives, especially if it concerns their property: a high level of trust and social capital is developed in the Homeowners’ Association, which contributes to joint activities and initiatives. Effective mobilisation and collective action are possible when they are based on organisational structures. This allows for better communication, reduces the entry threshold and risks, ensures coordination and decision-making, and is a key factor in the duration of the initiative’s existence. Many other studies on Moscow activism are illustrated by examples of regular large and smaller initiatives concerned with the protection of squares and parks, the organisation of grassroots environmental or charitable services, self-organisation to help specific groups of citizens, etc.

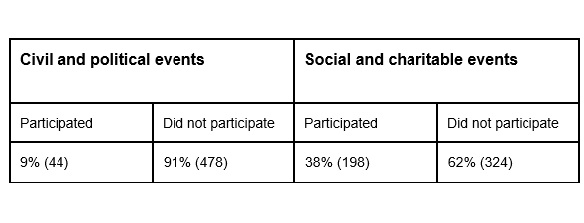

In my research, based on a representative survey of the Levada Centre in thirty districts of Moscow, I found that the participation of Moscow residents in political or near-political protests is not as common as it might seem. Along with this, Muscovites are used to participating in collective actions on social and charitable topics, and they do it regularly. This indicates the familiarity and even routine for Muscovites to participate in public initiatives, the need to coordinate action among themselves and to communicate on issues of public actions.

The involvement of Muscovites in the affairs of their properties (participation in meetings, etc.) and their involvement in district social networks and instant messaging groups were positively associated with participation in collective actions, as were the density of civic associations (shown by the number of NGOs in the area according to the Ministry of Justice). At the same time, the ability to organise is significant for collective actions of different types, and organisational infrastructure promotes the involvement of citizens in joint collective actions, regardless of the political significance or neutrality of the goals of mobilisation.

For modern Muscovites, associating is an important condition to participation in collective actions of various types: both politicised association in the form of public protest actions, and non-politicised in the form of charity or even subbotniki (a Soviet tradition of volunteer unpaid work on Saturdays, continued to this day in Russia). Various forms of association — NGOs, clubs, etc — allow to accumulate mutual trust between people, to discuss problematic issues of the district in messaging groups or at volunteer meetings, and to reduce the cost of coordinating actions and exchanging knowledge. In other words, political and social activism does take place among Muscovites and is a regular occurrence, even though it does not concern the majority.

Which Muscovites vote for the opposition?

The organisational factor is also meaningful to participation in elections, in combination with other social and structural characteristics. An analysis of the opposition’s representation in Moscow municipal councils following the results of the 2017 elections shows that the density of communications between district residents is a prerequisite for higher support for the opposition in Moscow municipalities. Interestingly, the organisational experience of Muscovites, that is, the experience of organising joint actions such as subbotniks or environmental actions, is not correlated to the opposition receiving more votes in an area. The Gagarin district is a special case: its Municipal Council of Deputies is the only example in Moscow of the ruling party losing in 2017 with an overwhelming majority of votes being received by Yabloko. This level of support for the opposition is associated with a significant density of communications between residents of Gagarin, a high level of non-personalised trust as well as with organisational experience.

Separately, it should be noted that the cost of real estate in a district is also linked to a higher representation of the opposition in the municipal councils of Moscow. This correlates with other studies that point to similar class-related political behaviour: residents of wealthier areas demonstrate greater civic and political activity. In terms of electoral behaviour, they are more oppositional.

Despite the significant cooling in Russian public policy and the tightening of the regime itself, social and organisational factors associated with the political behaviour of Moscow residents can only find their expression in real political action. We cannot predict the results of the elections in Moscow in 2022, but for now, elections are still a conventional form of expressing one’s political consent or disagreement. The complex and diverse district policy in Moscow will manifest itself in this year’s municipal campaign.