In July, the Kremlin held a constitutional referendum. This can be seen as the end of a long political cycle, one that started in 2014 with the annexation of Crimea, and ended with the emergence of a new Putin regime: one that is more repressive, intolerant, ideologised and conservative. This regime actually lives on an external agenda. All internal political processes are subordinated to geopolitical circumstances and a ‘besieged fortress’ logic. Its institutional foundations have been enshrined in the newly amended Constitution, which significantly strengthens presidential power, introduces elements of official ideology and blurs any prior separation of powers. This new constitutional rubrik also has another, more pronounced feature: an increasingly noticeable split between real decision-making processes and the official structure of governance.

Putin’s regime has always relied on shadow mechanisms for discussing and making political decisions. Indeed, this mechanic was not alien to Boris Yeltsin either. In Yeltsin’s time, it is enough to remember the influences of his notorious ‘family’. However, the overall trend in recent years has been to ‘dry up’ the official authorities politically; deprive them of political independence; and shrink the space for independent and autonomous operation within their functions. This happens when the Ministry of Foreign Affairs ceases to engage in diplomacy and turns into an advocate for the Kremlin instead. It uses rhetoric not very different from that applied by the most odious propagandists. This happens when the cabinet, instead of following a clear, strategically aligned economic policy, plunges into a contradictory implementation of ‘national projects’. This happens when social policy comes to life only on the eve of the constitutional referendum or before federal elections, and boils down to simplistic distribution of cash. And this also happens when the elections turn into an administrative routine — devoid of meaning, competitive struggle, or conversations about the future.

All this is accompanied by quite telling processes in personnel policy: the reshuffling of earlier this year confirmed an existing vector. Political heavyweights and experienced, sophisticated figures are pushed out of the official structures. They are constantly being replaced by young technocrats and performers. These arrivals are convenient for the president; they ask no questions and are well aware that beautifully presented figures make a much better impression on the country’s leaders than the real, sad picture. Nobody should be surprised if, in the next few months, this ‘technocratisation’ process extends onto the previously ‘untouchable’ structures such as the Foreign Ministry or the FSB.

The disempowerment of the official authorities, designed to make Putin’s work more comfortable and less politically controversial, leaves little room for initiative. In reality, only three types of activity are encouraged in public space: propaganda (information policy is more than creative), accounting (budget expenditures and revenues, management of sovereign funds) and ‘security’, i.e. countering external threats, fighting internal enemies and preventing revolts.

Nevertheless, the constitutional reform has awakened expectations: hundreds of posts in Telegram channels are dedicated to the forthcoming transformation of the State Council into a body resembling the headquarters of future transit of power, and the Council of the Federation into a super authority with new supervisory functions. One must not forget about the Security Council, Putin’s favourite platform for discussing the current strategic agenda. All this must be approached with great caution; expectations are unlikely to be fulfilled.

From an institutional perspective, the new Constitution does not vest the State Council with any real powers. This presidential advisory body is pretty much what it used to be; it is now forced to settle for a vague reference in the Constitution. The law on the State Council will likely soon be adopted, possibly one of the main ‘intrigues’ of the season. However, the new law is unlikely to contain provisions that could devalue the role of the cabinet, let alone the presidential administration. The profile of the State Council has slightly risen in the last two years. This was thanks to the curators of domestic policy who are on the lookout for mechanisms to influence official policies more effectively. Given how this body has previously played a purely decorative role, this ‘strengthening’ step can hardly be seen as significant: it results in a duplication of ‘expert’ functions rather than political reinforcement.

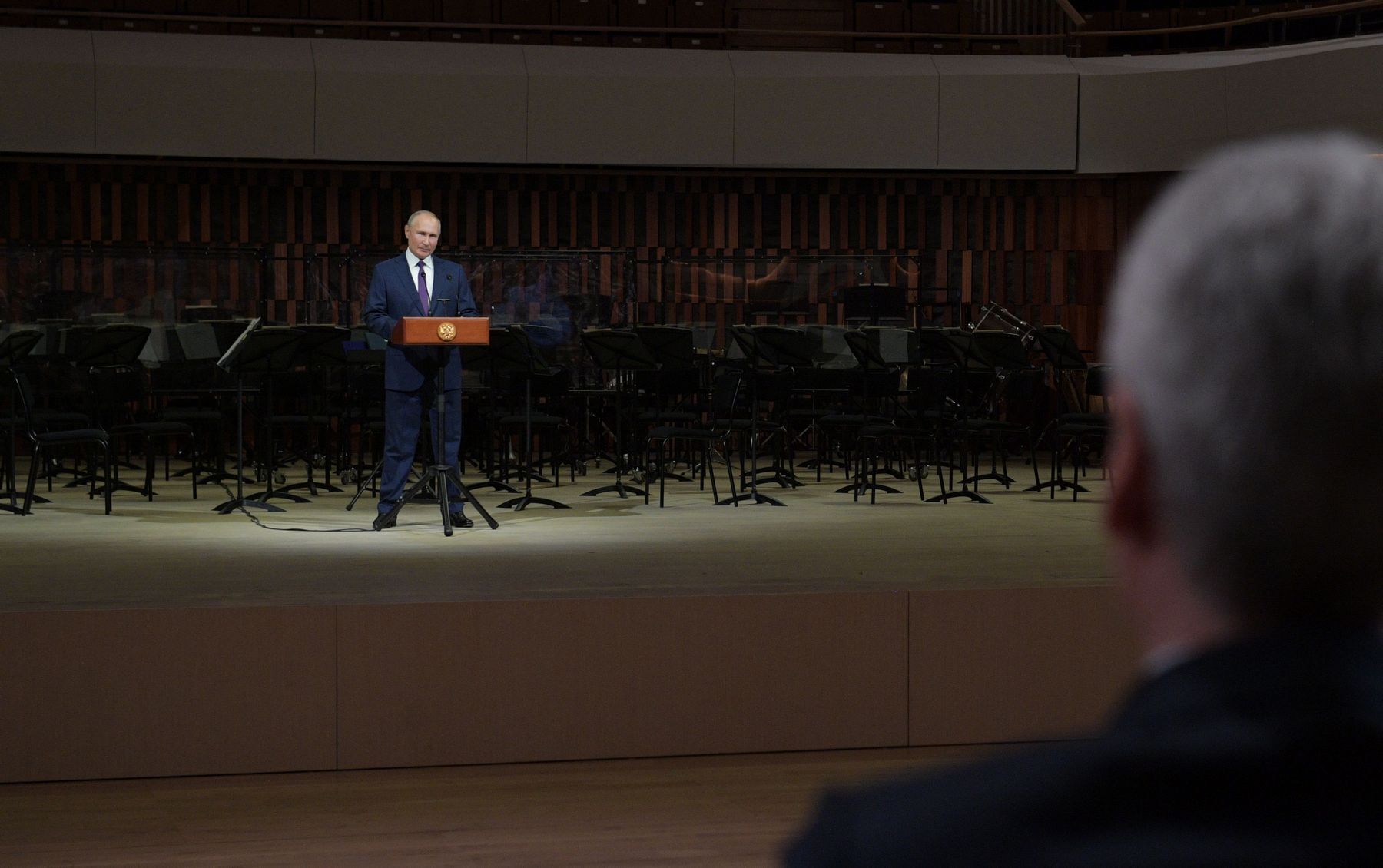

Expectations about the Federation Council have not yet been met. They are unlikely to be fulfilled. Putin’s recent speech to the senators proved to be routine and politically empty. Even the presidential quota which is soon to be filled in the Senate, possibly by the retiring heavyweights, would probably confirm the informal status of the upper house of parliament as a place for political retirees.

Even if important personnel choices or institutional decisions are made soon (and they are currently being discussed), they will lead to an even greater devaluation of the political role of official structures, improved comfort for Putin and lower governance costs. The official frame is increasingly turning into a screen, with its actors dwindling, and the agenda being at odds with real life.

At the same time, the real policies and the process of making strategically important government decisions is ultimately moving to the back burner. The entire agenda can be divided into two parts, unequal and with varying significance for Putin. The first one involves routine actions, which the President is happy to delegate to the FSB, the Prime Minister, the Central Bank and governors, without wondering how they are going to solve the problems. This is not the presidential level. We are seeing a broad Putin-less space emerge: the cabinet holds meetings, governors fight the coronavirus, the parliament hears reports and endorses laws written by unknown authors in the shadows. The President is constantly present within these processes but only as a background: he often delivers speeches and holds meetings but it all seems like a simulation.

However, some issues achieve the scale of the universe, like genetic engineering and bioengineering (the new ‘nuclear’ weapons), the outer space, history and geopolitics, or artificial intelligence. This set of issues is not simply too distant from the daily lives of ordinary Russians: they ‘suck Putin in’, disconnecting him from reality, leaving the public one-on-one with accountants, ‘guards’, controllers and administrators. Putin goes into detail only into issues which he thinks are suitable for his calibre, and the range of such issues has been constantly shrinking.

Behind the official frame, in the depths inaccessible to external observers, a completely different life is thriving, with ‘geopolitical entrepreneurs’ replacing the Ministry of Defence and the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, and loyal comrades-in-arms receiving meticulous missions. A special position is reserved for those who know how to stun others with nuclear developments, state-of-the-art weapons, biological research and the ability to read the human genome freely. For the first time in 20 years, the political role of the ‘family’, which the president has been hiding for so long, has crystallised as well. Nuclear medicine and genetics, artificial intelligence and biotechnology are the new foci of interest, attracting a young generation of special confidants, personally close to Putin, who are gradually replacing his aging comrades-in-arms.

There is a clear dissonance between these two worlds: the rigid and lifeless official frame on the one hand, and the dynamic, fascinating and intimate world of global achievements on the other. Putin seems to thin that he can afford to plunge into more ‘lofty issues’: after all, he thinks he has already solved one of the main problems of his presidency, i.e. he has built a stable, reliable system, which now needs to be put into the autopilot mode. The system comprises a strong party in power, a constructive opposition, strong barriers to non-systemic elements, a loyal cabinet and responsible elites. This opens up an opportunity for Putin to turn towards a completely different world: a world of miraculous transformations, breakthroughs, unprecedented technologies and achievements.

One of the main problems in this design of reality is that it offers an inadequate response to the real challenges that arise in everyday life. Social instability, disturbed dialogue between the authorities and the society, politics of persuasion replaced with politics of coercion, disproportions in economic development, reduced ability to establish channels for the system to release steam – all this is happening in the context of Putin’s devaluating political leadership and poses critical risks for the regime. Given the current turbulences, the regime may simply become powerless vis-à-vis the challenges in governance and politics. The logic of things ‘easing off by themselves’ was particularly vivid during the Khabarovsk protests. The main threat to Putin is not the real opposition, but the loss of the ability for the system to respond emerging problems in an adequate and timely manner, which is a likely future outcome of the ongoing devaluation of official institutions and authorities.