The past year of 2023 saw gradual organisational degradation of the Russian army, a development that seems hardly reversible until the end of the war. This includes: the creation of volunteer formations reporting to the Ministry of Defence that are not regular units; the mass recruitment of prisoners; the decision not to show resistance ‘on the ground’ vis-à-vis the mutiny of mercenaries in June 2023, with the subsequent incorporation of some mercenaries into the said volunteer formations; and the use of understaffed regular units recruiting military personnel from other types and branches of the army.

Against this backdrop, the material and technical degradation occurred throughout the year: the long-decommissioned T-55 and T-62 tanks and D-10 and D-20 howitzers returned into service, North Korea was approached for artillery shells and Iranian drones were used commonly instead of cruise missiles. For his part, Nikolai Patrushev openly urged the central regions of Russia to draw up economic mobilisation plans at regional and local levels, which is at odds with the official claim that Russia is ready for a protracted war.

However, the Kremlin continued to transform motorised rifle brigades into divisions, create new general armies, appoint generals en masse and report on recruiting hundreds of thousands of contract soldiers, increase the staff size in the regular armed forces and promise even more contract soldiers in 2024, while increasing military spending in parallel.

Nevertheless, ever more insistent voices can be heard from Moscow about the need for a pause in the war, and Vladimir Putin has, perhaps for the first time, openly admitted that the nuclear threats from Russia are designed to force the US and its allies to negotiate.

As a result, all these contradictory data and actions reveal a general progressive military depletion in Russia, which will continue into 2024. This depletion does not mean that we can write the Kremlin off the books and let the ‘swinging mood’ take over. After all, in addition to returning Ukraine to internationally recognised borders, the most difficult long-term military and political task in this war is to ensure that the Russian authorities and Russian society become unable, incapable and unwilling to threaten their neighbours, attempt historical revenge and restore the empire.

Overestimated number of contract soldiers

In December 2022, the Russian Ministry of Defence announced a plan to have 1.5 million people in the regular armed forces by the end of 2026, where 695,000 positions should be staffed by contract servicemen (soldiers, sergeants, warrant officers, etc.). At the same time, by the end of 2023 the armed forces were supposed to have 521,000 contract soldiers. In December 2023, the plan was revised: by the end of 2024, the Russian Armed Forces should have as many as 745,000 contract servicemen. However, this kind of game with numbers is only possible if it involves the army size on paper or in accounts but not live servicemen.

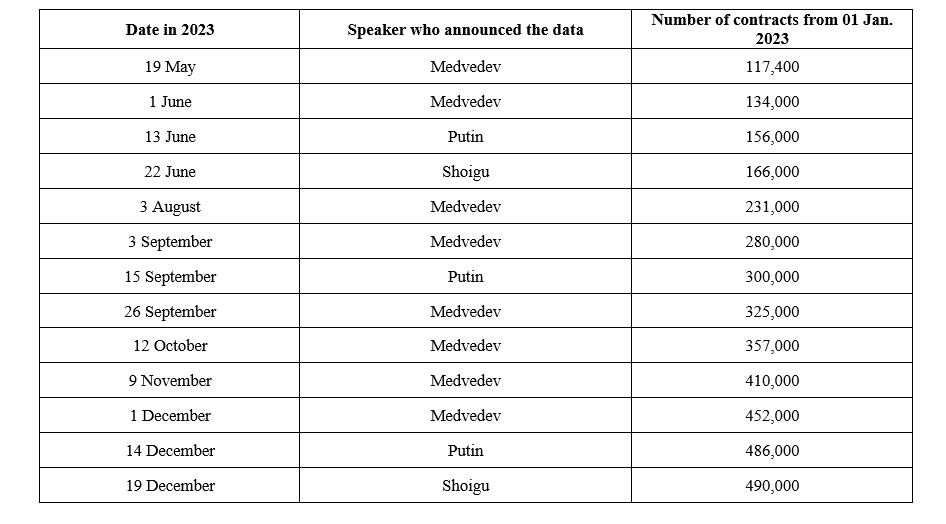

Even if we look at the published trend in contract-based recruitment figures throughout 2023, what we see is not simply a linear process but an ever-accelerating one:

Table 1. Chronicle of Russian leaders’ statements on the number of military service contracts signed in 2023

It turns out that between January and mid-May 2023, an average of approx. 6,000 military service contracts were concluded every week, and this number leapt to the range of 10,000−17,000 per week from 19 May onwards, averaging 12,000−12,500. There is no clear explanation for this doubling of figures except that we are dealing with an obvious bureaucratic campaign to achieve the required figures at any cost.

Firstly, the most recent public data on the number of contract soldiers before 2023 were given by the Ministry of Defence back in March 2020, when the figure stood at 405,000. There is no reason to believe that by February 2022 the number of contract soldiers in the Russian armed forces differed significantly (by more than 5%) from this figure, either upwards or downwards. It should be remembered that the official number of contract soldiers in 2017 was 384,000, and the target of 500,000 was planned to be reached not earlier than by 2027. In other words, under the conditions of war, the Ministry of Defence somehow managed to complete a task that it was unable to achieve throughout many years in peacetime.

Secondly, from 24 February 2022 onward and until the start of partial mobilisation on 21 September 2022, i.e. in the first six months of the full-scale war, the Russian army faced not only high losses, but also an increased number of those who would like to leave it early. This was in addition to soldiers whose standard two-year contracts had expired or were about to expire (a contract is considered to be in its final stage six months before the stated termination date). All of those soldiers were kept in the army as a result of mobilisation. At that time, the number of such mobilised contract soldiers could be roughly estimated at 100,000−150,000 people, and this number could only grow in the future. This created uncertainty about the status of those contract servicemen: do they continue to serve in their positions as contract soldiers without a contract, or with their contracts automatically extended indefinitely, or perhaps as mobilised servicemen with appropriate payments?

Thirdly, because of the attempted mass recruitment of people, including foreign nationals, under short-term contracts (from a few months to one year) into volunteer formations that are not part of the regular army, the mass recruitment of prisoners into six-month contracts to serve in assault squads and the incorporation of some Wagner- and Akhmat-group mercenaries, the same person could have signed at least two contracts within the same year once the first contract was terminated.

Hence, a significant proportion, if not the majority, of the 490,000 contract soldiers (as of 19 December 2023) comprised existing contract soldiers who were forced to sign new contracts. This figure also included prisoners and members of volunteer formations, who could sign more than one short-term contract in the course of 2023 and, consequently, could have been counted as new contract soldiers at least twice.

Of course, there were also genuine new contract soldiers in the Russian army: for some, it was a way to improve their poor financial situation, for others — an opportunity to hide from the war in the types and branches of the army that are not involved in it, while it was a conscious choice for others. Also, the scale of the transition of mobilised men into military contracts is difficult to estimate. Likewise, it is not clear how long those who are formally missing in action, captured or disabled continue to be listed as contract servicemen.

Nevertheless, if we disregard volunteers, prisoners and mercenaries, we can say with a high degree of certainty that by the beginning of 2024 the Russian armed forces will not have recovered the number of contract-based personnel that they had on the eve of February 2022. This is indirectly evidenced by other figures cited by the Kremlin: approx. 244,000 military personnel are officially at war today, while 650,000 people have gained combat experience since February last year, 458,000 of whom have already received certificates confirming their status as combat veterans. This, of course, includes both regular servicemen and mobilised personnel from various combat units, as well as those serving in the navy and combat support units, ground staff of military airfields, etc., servicemen of the Rosgvardia and Federal Security Service (FSB), mercenaries and volunteers, military personnel from the Donetsk and Luhansk People’s Republics, as well as police officers. And apparently, these 650,000 veterans include all: the living, the dead, the missing, the captives and the disabled.

And given the Russian servicemen’s numerous complaints about the lack of rotation, it is not clear—even taking all the losses into account—where the claimed 490,000 new contract soldiers could have dissolved, alongside the unclear number of ‘old’ contract soldiers and the remaining mobilised troops. Simply put, the figures on paper have ultimately diverged from the actual number of people in Russian troops.

This situation is aggravated by the systematic increase in the maximum number of regular military personnel, which began as early as 2022: starting from 1 December 2023, this number was set at 1.32 million people. About 170,000 new positions have been added to it, compared to the previous decree of 25 August 2022, when it was increased by 137,000. Thus, in just 15 months, the number of regular servicemen of the Russian armed forces rose by almost 307,000 people, and should go up further by another 180,000, up to 1.5 million people.

In other words, the discrepancy between the figures on paper and the real strength of the army will continue to widen. However, the maximum personnel figures entail corresponding financing and expenditures associated with the official defence orders. In fact, this seems to be the main reason behind all these moves. The Ministry of Defence wants to maintain the greatly augmented military budget regardless of the situation on the battlefield. Moreover, in the event of the much-expected respite in the war, this formally established personnel figure will serve as a formal justification for expenditures to rebuild the armed forces before a new round of aggression. At the same time, the warring army will continue to face a deepening shortage of soldiers and officers, as evidenced by the de facto abandonment of the plan, announced in December 2022, to replace those mobilised soldiers. This will exacerbate issues related to manning, discipline and combat capability. If the intensity of hostilities remains at the 2023 level, the Kremlin will be forced to take unpopular measures, which could include both regular deployment of units from other branches and types of the armed forces, and even other security agencies to the war, and an attempt to conduct a new wave of mobilisation.

Arms production: No miracles here

Against the backdrop of the campaign to increase the number of contract soldiers, Russian leaders never tire of convincing the world that they have been able to multiply the production of weapons and military equipment. The enterprises from the arms industry also report that they have fully executed orders from the Russian military, sometimes even before the deadlines.

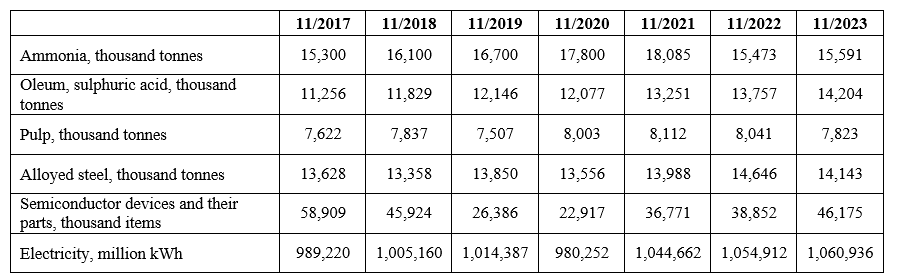

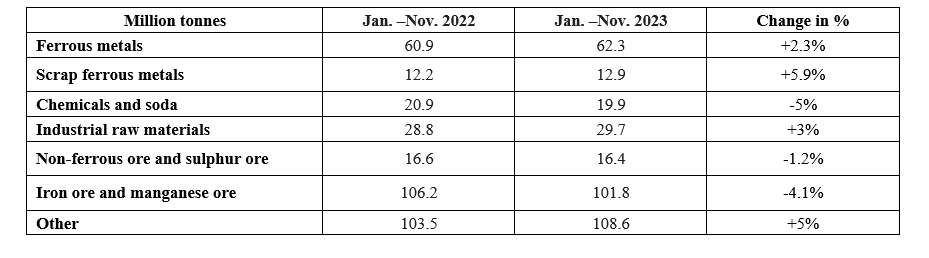

While the final statistics for the whole of 2023 are not yet available, we do have some data on industrial production in volume terms, as well as data on shipments in the Russian railway system for the period from January to November 2023. These data do not confirm the hypothesis that the material- and energy-intensive Russian military industrial sector is experiencing unprecedented production growth.

Table 2. Output of selected products used in the manufacture of armaments and military equipment, in volume terms, 2017−2023, January-November

Table 3. Shipments of certain cargo categories in the Russian railway system, January-November 2023, compared to the same period in 2022.

Of course, these indirect data do not deny the fact that some growth in military production is taking place in the Russian military industrial sector. However, this growth stems from a number of reasons. Firstly, these are stocks of materials and components that had been accumulated earlier. Secondly, this growth can be seen as a recovery after a serious collapse, as evidenced by the example of semiconductor devices in Table 2. The same holds true for the production/modernisation of main battle tanks, with a peak in the late 2010s (over 200 units) and a near halving in 2021 (to less than 100 units). Thirdly, the country is using military equipment that was taken from storage bases still remembering the Soviet times, and sent to factories for refurbishment repairs or ‘cannibalisation’, and there are ongoing factory-based repairs of combat vehicles. This is where, for instance, the declared «1,530 new and modernised tanks, 2,518 armoured infantry fighting vehicles and armoured personnel carriers» originated from. Fourthly, in 2023, the sector put into operation the workshops and upgraded production lines where investments had been made before February 2022, when Russia still had relatively free access to Western industrial equipment and components.

At the same time, the potential for boosting the production of armaments and military equipment thanks to the stockpiles and a low base appears to have been largely exhausted in 2023. As a consequence, the main headache of the Russian military industry in 2024 will not be to elevate its performance indicators further, but to maintain the current rates of production, modernisation and refurbishment. And the fact that Russia has to resort to systematic military and technical assistance from Iran and North Korea indicates that the Kremlin has recognised Russia’s own industrial capabilities as insufficient.