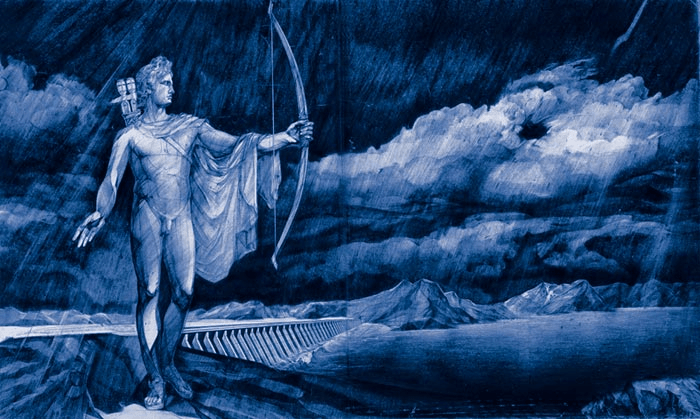

Despite statements from Russian officials about a “turn towards Asia” and the Russian media’s “anti-Western” rhetoric, the government’s cultural initiatives of the past few years tell another story: In the search for a national image, priority is accorded to anything portraying Russia as the “true” Europe, a European Christian civilisation rooted in Greek and Roman culture.

The construction of this image lies behind the new surge of interest in so-called “Soviet” antiquity and the melancholic idea of the Soviet Union as a sunken Atlantis, as depicted succinctly by Eduard Limonov in the title of his 2014 poetry anthology The USSR is our Ancient Rome.

On the one hand, such a strategy for national image-building strives to depoliticise and mythologise the Soviet legacy. On the other, however, it creates a picture of Russia that is not a “Eurasian civilisation” or a civilisation with a “special path”, but rather a guardian (katechon) of classical European tradition, protecting it from barbarian fundamentalists and Europeans who have lost their “civilisational memory”.

“Post-Crimean” cultural policy differs not only in its stricter control over cultural activities, but also its much more distinct ideological line, which presents Russia as the main ally of European Christian civilisation. In this ideological construct, the terms Europe and the West are split (“the West” is defined as liberal multiculturalism, in which Europe’s Christian foundations are suppressed). Europe is mentioned without the West, prioritising old Catholic Europe and particularly Italy.

Up until the events in Ukraine and Syria, such ideas were limited to neo-conservative subcultures (mainly within new Eurasian and right-wing circles), but in recent years they have been actively present in the political and cultural mainstream. Such a model allows the regime to criticise the nominally “liberal” and mostly protestant West, while simultaneously asserting its role in the international community as the final shield capable of defending the traditional values of old European culture. For example, Russia’s actions in Syria are presented as upholding true European values. The open-air concert by the Mariinsky Theatre Orchestra, conducted by Valery Gergiev, in the freshly “liberated” Palmyra on May 5, 2016 was a symbolic act designed to demonstrate the triumph of Russia’s civilising force over a new barbarism, the Islamic State. Pieces by Bach, Prokofiev and Shchedrin were played at the concert, an event christened “Pray for Palmyra. Music Revives Ancient Ruins”. All of a sudden, the antiquity embodied in the 2nd-century Monumental Arch of Palmyra – well-known to millions of Russians from their (Soviet) 5th-grade textbooks on ancient history – became animate and tangible, and (according to the official version) Russia had acted as its main and only defender.

This ideological project is one of many that the authorities are “testing”, but it seems this version of national identity is workable both at home and abroad (since it is capable of winning Russia allies in Europe and reopening splits inside the EU along old confessional divides of a Catholic South, a Protestant North and an Orthodox East). Little surprise, therefore, that it is currently receiving major support from the state.

Ancient, Christian Rome

The most obvious evidence of this “turn towards Europe” is the new exhibition policy of the country’s main museums – the Hermitage, Tretyakov Art Gallery, and Pushkin Museum of Fine Arts. Russia has now begun to position itself more actively as a country that knows and cherishes European heritage and Western Christian culture. A range of cultural events in 2016–17 are indicative of this: especially the exhibitions Raphael. The Poetry of Image. Artworks from the Uffizi Galleries and other Italian collections and Giovanni Battista Piranesi. Before and After. Italy–Russia. 12th–15th centuries at Moscow’s Pushkin Museum in Autumn 2016.

That year’s main event was undoubtedly an exhibition at the Tretyakov Gallery: Roma Aeterna. Masterpieces of the Vatican Pinacoteca. Bellini, Raphael, Caravaggio, which took place from November 25, 2016 until February 19, 2017. Although the exhibition’s title – “Eternal Rome” – is a reference to antiquity, audiences were presented with Italian religious art from the 12th–18th centuries. The exhibition’s curator was Arkady Ippolitov, a famous art historian from Saint Petersburg and curator of the Italian prints at the Hermitage. This is how he described his concept of the exhibition:

“Roma Aeterna implies the huge cultural unity that Rome has become for human history – a city which is both ancient and modern, and which managed to bring together completely different periods: Antiquity, the Middle Ages, the Renaissance and the Baroque. Rome is the centre of the empire, religion and arts: it could be said that the Roma Aeterna concept is one of the most important ideas in human culture. This exhibition is dedicated to that idea”.

In 2017, the Pinacoteca will host a return exhibition of masterpieces from the Tretyakov Gallery: Russian Gospel art from the 19th and early 20th centuries (paintings by Aleksandr Ivanov, Golgotha by Nikolai Ge, Christ in the Desert by Ivan Kramskoy). Vladimir Putin and Pope Francis agreed to exchange Russian and Italian exhibitions of Christian art during a meeting in 2013, and it was confirmed at a personal meeting between Patriarch Kirill and the Pope in Havana in February 2016.

In an interview for Rossiyskaya Gazeta, the Tretyakov Gallery’s director, Zelfira Tregulova, emphasised the uniqueness of the Roma Aeterna exhibition and its ideological component:

“Never before has the Vatican’s Pinacoteca collection provided 42 prestigious masterpieces simultaneously for an exhibition abroad. Of course, this is an extraordinary gesture which shows that, at such a difficult moment for the whole world, there is such trust in relations between Russia and the Vatican, the Vatican Museums and the Tretyakov Gallery”.

These meetings and exhibitions could be viewed as an important diplomatic step, the start of a new dialogue between Orthodoxy and Catholicism – not dialogue confined to the impasse of ecumenical discourse, but a new cultural, political cooperation. I would note that this unexpected turn by the state and the church towards dialogue with Catholic Europe has come under fire from both Orthodox fundamentalists and the liberal intelligentsia, who see it as an attempt by the authorities to form an alliance with the most conservative segment of the European Union.

Byzantine antiquity

The Roma Aeterna exhibition has revived the topic of the Three Romes. Articles with related titles started to appear in the media; for example, “From our Rome to your Rome”, “From the First Rome to the Third”, etc. However, the discourse regarding the Third Rome has acquired a new connotation nowadays. Unlike, for example, the radical imperialist projects from conservative circles, official rhetoric is not underlining Russia’s messianic exclusiveness as the last Rome, but rather the dialogue with the cultures of the First and Second Romes. We may again quote Tregulova, an official who expresses the Kremlin’s official position:

“It is no accident that the exhibition begins with religious paintings from the 12th-century Roman icon school, in which the Byzantine tradition is clearly present. But at the same time, we are not accentuating the peculiarities of iconography or interpretation of specific religious subjects in European masters’ paintings because, in my opinion, such projects are not about what divides us, but about what unites us”.

The same issue of dialogue, as well as the succession and close ties between Russia and Catholic Europe, are promoted in the 2016 TV series Sofia. It portrays the life of the Byzantine princess Zoe-Sofia Paleologue. She grew up in Rome and wedded Ivan III, the Grand Duke of Moscow, who laid the foundations for Russia’s imperial statehood. The series is funded by the Russian Ministries of Culture and Defence. Despite its vital ideological component being Sofia’s commitment to Orthodoxy (not Catholicism), which she adopted in Rome, the emphasis is placed on Muscovy’s participation in the political life of 15th-century Europe.

Previously, for example, in Tikhon Shevkunov’s famous 2008 film Fall of an Empire—the Lesson of Byzantium, Europeans were depicted as negative caricatures. Yet Sofia shows the Vatican and the Italian Renaissance culture, which the Byzantine princess brought to Moscow from Rome, in a positive light.

Soviet antiquity

Building up Russia’s image as a “European civilisation” is not limited to a penchant for Roman and Byzantine antiquity; there is also renewed interest in so-called “Soviet” antiquity. This can be illustrated by numerous recent urban renovation and exhibition projects.

A visualisation of Russia as a country with a great European culture was presented at the opening ceremony of the 2014 Sochi Winter Olympics. However, the main symbol of this new European Russia was meant to be the Italian-style “Gorky Gorod” ski resort in Sochi. The resort was designed by architect Mikhail Filippov, a “new Zholtovski”, one of the renowned “paper architects” of the late-Soviet period, and the leading neoclassicist in post-Soviet Russia. Mikhail Filippov describes the peculiarities of the “Gorky Gorod” project, in which the main aim was to create the illusion of an ancient city:

“The main technique was to build houses not just in a classical style, but like a city, to create the illusion of a city built around the ruins of a Roman amphitheatre. Italian and Spanish seaside towns are built this way, as is the Piazza della Repubblica in Rome”.

On the other hand, the architect describes Stalinist neoclassicism as the main style in the area:

“International environmental certificates take into account whether an architectural style is consistent with local tradition. Sochi’s local tradition (vernacular) is 1930–1950s’ neoclassicism. I followed that tradition”.

Before this project, Filippov built the “Roman House”, the “Italian Quarter” and the “Marshal” residential complex in Moscow, totalling 750,000 square metres of neoclassical buildings.

“Restoration of utopia” has become a hallmark in recent years – large-scale projects to renovate Stalin-era architectural monuments. One of the first scandalous examples was the refurbishment of Kurskaya-Koltsevaya metro station in Moscow in 2009, where the last lines of one edition of the USSR national anthem appeared on the entrance-hall walls: “Be true to the people, thus Stalin has reared us, Inspired us to labour and valorous deed”. Responding to criticism, the renovators explained that they had restored the station’s appearance to the way it looked on the day it opened — January 1, 1950.

Since then, interest in renovating monuments of Soviet antiquity is on the increase. It is revealing that the term “totalitarian style” is now being replaced by “Stalinist antiquity” and “Soviet art-deco” which, apart from their more positive connotations, add some global (especially American and European) context to Soviet neoclassicism.

The largest restoration projects in recent years have been the reconstruction of Gorky Park and VDNKh, the renovation of the Kotelnicheskaya Embankment Building in 2015–16, the remodelling of Tverskaya Street (widening pavements, planting trees) and, of course, the demolition of the trade pavilions in Moscow’s historical centre in 2016 — a crucial symbolic act which marked the end of spontaneous post-Soviet capitalism (the so-called “kiosk civilisation”) and the victory of a state which mostly associates itself with imperial Stalinist style.

On the other hand, we also observe how Stalinist architectural complexes (Gorky Park and VDNKh in particular) are being appropriated by urbanists who are annihilating the ideological component to transform them into neutral, urban recreational spaces. To remind you, the Moscow renovation project was developed by KB Strelka, with the active participation of Grigory Revzin – a professor at the Graduate School of Urban Studies of the Higher School of Economics – whose influence on the renovation programme for Moscow’s neo-classical-style public areas was substantial. At the start of the 2000s, Revzin was in charge of the “Classics” project, in which much attention was paid to analysing the history of Stalinist neoclassicism, and he is also the author of the famous monograph “Neoclassicism in Russian architecture of the early 20th century”.

The importance of Soviet antiquity for building and visualising a post-Crimean national identity is best illustrated by the Russian pavilion at the 15th Venice Architecture Biennale (May 28–November 27, 2016), where Russia presented a multimedia exhibition dedicated to the past and future of the VDNKh complex. In the first room, a video presentation set to music by Shostakovich informed spectators about key historical facts and figures. It showed three scenarios for the possible fates that such architectural ensembles have met worldwide: destruction (Palmyra), museumification (the Roman Forum; Versailles) or revitalisation (VDNKh).

***

In a domestic-policy context, we can assume that the new universalist “Russo-European civilisation” project aims to oppose ethno-nationalistic movements inside Russia itself, and in terms of foreign policy, it contrasts Ukraine’s internal nation-building on the one hand, with Western discourse about Russia’s “barbarism” and provinciality on the other. The global horizon of the country’s cultural policy is currently being emphasised in every possible way – a country that, according to Putin, not only has no geographical borders, but also no limits in historical timeframe.