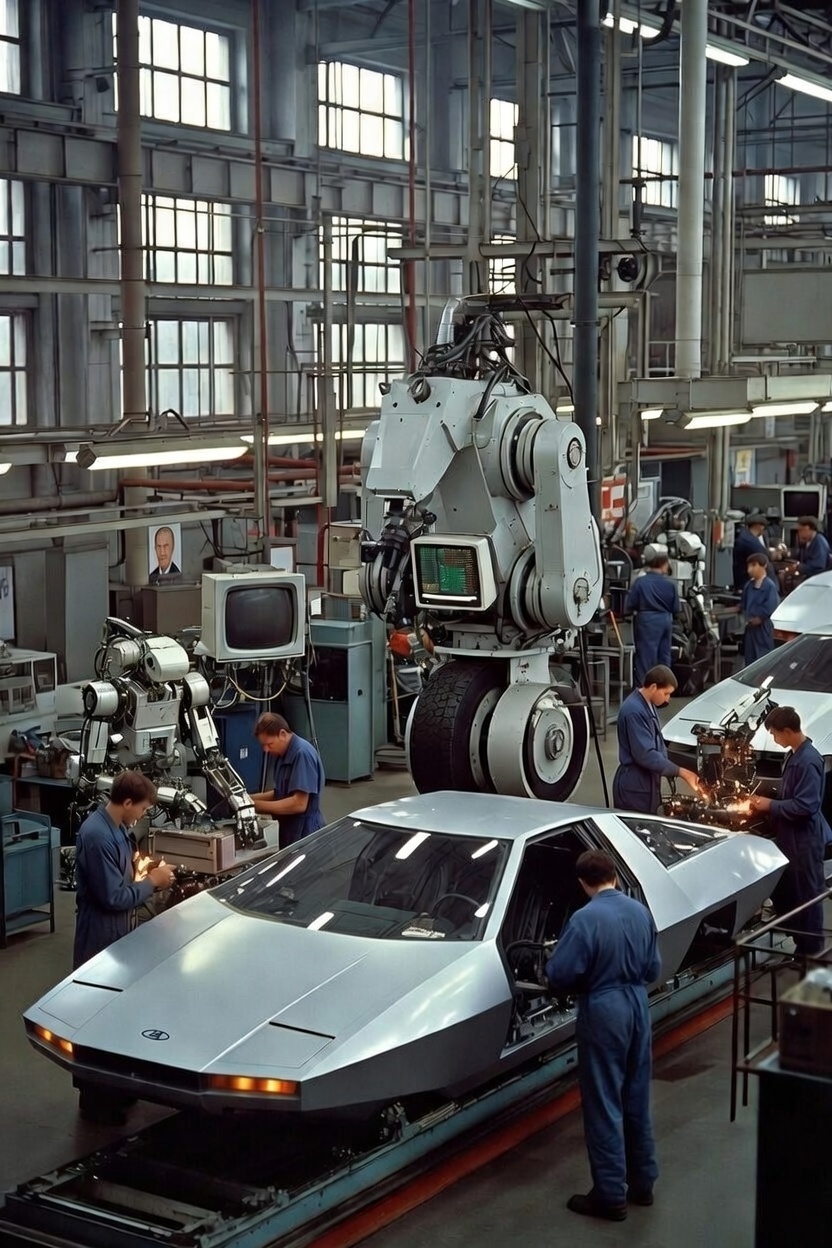

Russia’s air campaign against Ukraine’s power and heating systems has reached a crescendo amid a dangerously cold winter, and the announced pivot to technological sovereignty is now receiving a new spin. At Denis Manturov’s behest, MinPromTorg has asked state corporations to provide concrete plans for moving toward people-less, fully or mostly automated production. Given labor shortages, it is unsurprising that the state is seeking to boost labor productivity by adopting best practices from industry elsewhere—particularly China. Many questions remain unanswered, chief among them whether officials plan to import industrial robotics or launch another subsidy program to produce them domestically. The former option is much faster and cheaper, but it does not deliver the sovereignty that officials claim to seek. Still, it addresses the immediate problems facing officials who are trying to generate the sense that things aren’t going off the rails.

It has become the «common sense» position that declines in consumption or living standards do not pose a material political threat to the regime so long as they prevent any widespread sense of inequality about those declines. To me, this is a very unsatisfying framing: it substitutes careful analysis of the wartime economy’s pathologies with appeals to the regime’s record of actively managing said declines. My reasoning, if imperfect, is fairly straightforward: the worse stagnation or stagflation becomes, the more the regime must actively intervene in economic processes in ways that create pathways for mounting coercive pressure on the public and on business. Precarity works as a disciplinary tool only so long as this active effort can be moderated or fragmented in ways that atomize social responses. The pathologies of the wartime economy cannot be undone by a peace deal, and they will test officialdom’s management capacity—oscillating between ostensibly technocratic fixes and more visibly unfair practices.

The issue of labor shortages is here to stay. Unemployment remains at historic lows, yet annual inflation for 2025 came in at 5.59%. If we assume the 1% GDP growth figures for 2025 are believable, this would suggest that real wages are not rising. Yet Rosstat’s data shows that labor’s share of national income for Q1-Q3 2025 was the highest it has been since the invasion. The number of small and medium-sized businesses grew by 200,000 last year to a historic high of 6.76 million—an indication that arbitrage created by sanctions, wartime needs, and policy interventions is encouraging more Russians to work for themselves or for smaller firms that earn profits from what they can mark up or deliver efficiently within their constraints.

That should, on paper, be reflected in rising productivity. However, it is likely not the kind of productivity the regime particularly cares about at the moment—when it needs to stretch the manufacturing capacity of an economy that increasingly cannot afford to invest without state support (interest rates are too high) and needs to reduce wage pressures from inter-sector competition. Right now, the biggest inflation pressures come from utility and rail tariff increases and similar idiosyncratic factors. These reflect another aspect of the same problem: dramatic underinvestment has created scores of «ghost» demand for power and heating from losses in transmission, distribution, and leaky pipes. Consumers are increasingly being forced to pay for the state’s long-standing refusal to borrow adequately to finance capital investment. What follows is a game of whack-a-mole. Every time an effort arises to address a specific source of price increases, it creates pressure on another weak point. Interest rates must fall significantly to make this more manageable for the private sector.

How does this relate to industrial robots? Building roboticized factories should expand production of various things—presumably largely military inputs. There will be jobs repairing and managing these robots and assembly lines, and they will likely be well-paid. But the amount of human labor needed per factory will decline. Robots don’t collect wages or pay taxes. Whatever labor is freed up must find productive employment elsewhere. This is where automation collides with the contradictions of the wartime economy. Using robots to build weapons requires large volumes of capital to be invested—capital that would likely struggle at current interest rate levels without one of two things: subsidies or confidence that prices for whatever is being produced can be raised high enough to rapidly reach profitability and service debt.

But if robots make weapons, the state will be consuming them, and they will do absolutely nothing for the rest of the economy. They will not be served in restaurants, nor sold at retailers, nor help in emergency rooms or schools. The hope would be that automation might reduce the costs of state procurement. In reality, it creates a labor allocation problem. Men who have worked in manufacturing will want to maintain their wages. If they stay in the sector or have to reskill, they will not be producing much additional GDP on paper unless they are making consumer goods. There is no evidence that consumers are prepared to spend more money on products that—even with robots—would be more expensive to produce domestically than to produce in China. Demand for storage space has declined 40.5% according to Domklik—a figure that suggests people simply cannot manage to accumulate that much more stuff.

So imagine a scenario where more laborers face pressure to demand comparable wages in manufacturing or other sectors while consumers increasingly struggle to buy more products. Perhaps some of that is offset by spending more on services while delaying home or auto purchases, but that would inevitably increase services-based inflation, which tends to be stickier than goods inflation. You get a scenario where regime officials will be hounding businesses to keep paying well and investing to offset any labor dislocations from automation. If automation suddenly brings down production costs for an intermediate good—think machine tool-type inputs—then any small businesses that popped up benefiting from sanctions or the wartime economy, and supplying these inputs at smaller scale than state corporations, will begin to go under.

The larger point of this otherwise meandering thought experiment is that a productivity breakthrough is useless for GDP if it is concentrated in military industries. What ends up happening instead is a conflicting mess of pressures to keep wages higher—adding to inflation—and potential disruptions to the industrial economy focused on intermediate or civilian products. The only way these sorts of contradictions in a supply-constrained economy resolve without a contraction of economic activity will be direct intervention: phone calls, price fixing, wage negotiations, punishment, nationalizations to fix a market failure. The subtle accretion of signals that the regime is encumbering economic life—and therefore private lives—ever more actively.

Collapse is a stupid word in the Russian context. The economy collapsed with the USSR, yet countless forms of exchange and activity continued. It is better to think in terms of institutional capacity and arrangements. The more the regime tries to engineer a great leap forward into the industrial future, the more active its interventions become into an economy it has mismanaged and underdeveloped. There will always be islands of success, nor will the entire picture be horrifically bleak. However, a large, sustained decline in consumption is a first-order crisis for the simple reason that without it, the wartime economy becomes impossible to maintain without directly ordering and reordering labor and business in a manner that undoes the very life of consumption the regime has cultivated to offer the public as a means of retreat from political reality.