The large-scale protests that swept across Kazakhstan, coupled with the attempted rebellion and coup d’état, captured the attention of the Russian expert community for some days, but experts swiftly moved on to other topics, particularly once it became clear that the Russian peacekeepers were not going to stay in Kazakhstan and that the announced restoration of the Russian empire would not take place overnight.

Meanwhile, it should be borne in mind that the events in Kazakhstan are markedly different from the numerous instances of destabilisation observed in the post-Soviet space over the past two decades. The thread which began with the «Rose Revolution» in Georgia in 2003 and the «Orange Revolution» in Ukraine in 2004/05, ran through the events in Moldova in 2009, Russia in 2011, Ukraine in 2013/14, Armenia in 2018 and Belarus in 2020. These revolutions, whether successful or not, had a common cause: the people were unwilling to tolerate the authorities’ cynical breaches of their duties (to ensure fair elections) or promises (as was the case with the signing of the EU association agreement in Ukraine or the change of political system in Armenia). Not a single post-Soviet country, however, saw a situation where economic hurdles triggered nationwide protests that would threaten to topple the authorities.

Kazakhstan has become an exception in this respect, especially given that the 2011 protests in the western regions of the country and the spectacular 2016 protests over the land reform were driven by value rather than values. The republic, which can boast strong economic performance (Kazakhstan’s GDP per capita is 2.1 times higher than that of Ukraine; oil, gas and uranium production has increased, respectively, 3.3, 6.3 and 15 times during the post-Soviet period whereas significant foreign investment originate, in 79.6%, from the USA, UK, EU and Switzerland), faced the outrage of the urban poor, deprived of access to growing national wealth (according to KPMG, towards the end of Nazarbayev’s era, about a half of Kazakhstan’s national wealth was owned by under 200 particularly prominent citizens). The social explosion was accompanied by a high inflation rate (8.70% year-on-year, based on the latest figures), considerable (9.9% to 25%, according to different sources) poverty rate (incidentally, official statistics mockingly claim that «poor» citizens are those with incomes below 70% [!] of the minimum subsistence level), and rapidly growing population, with the average age in the past year not even reaching 32. At the same time, as a country with a liberal economy but an authoritarian political system, Kazakhstan underwent decades of contradictions accumulating due to the nature of a «commercial state» where power and business are inseparably intertwined.

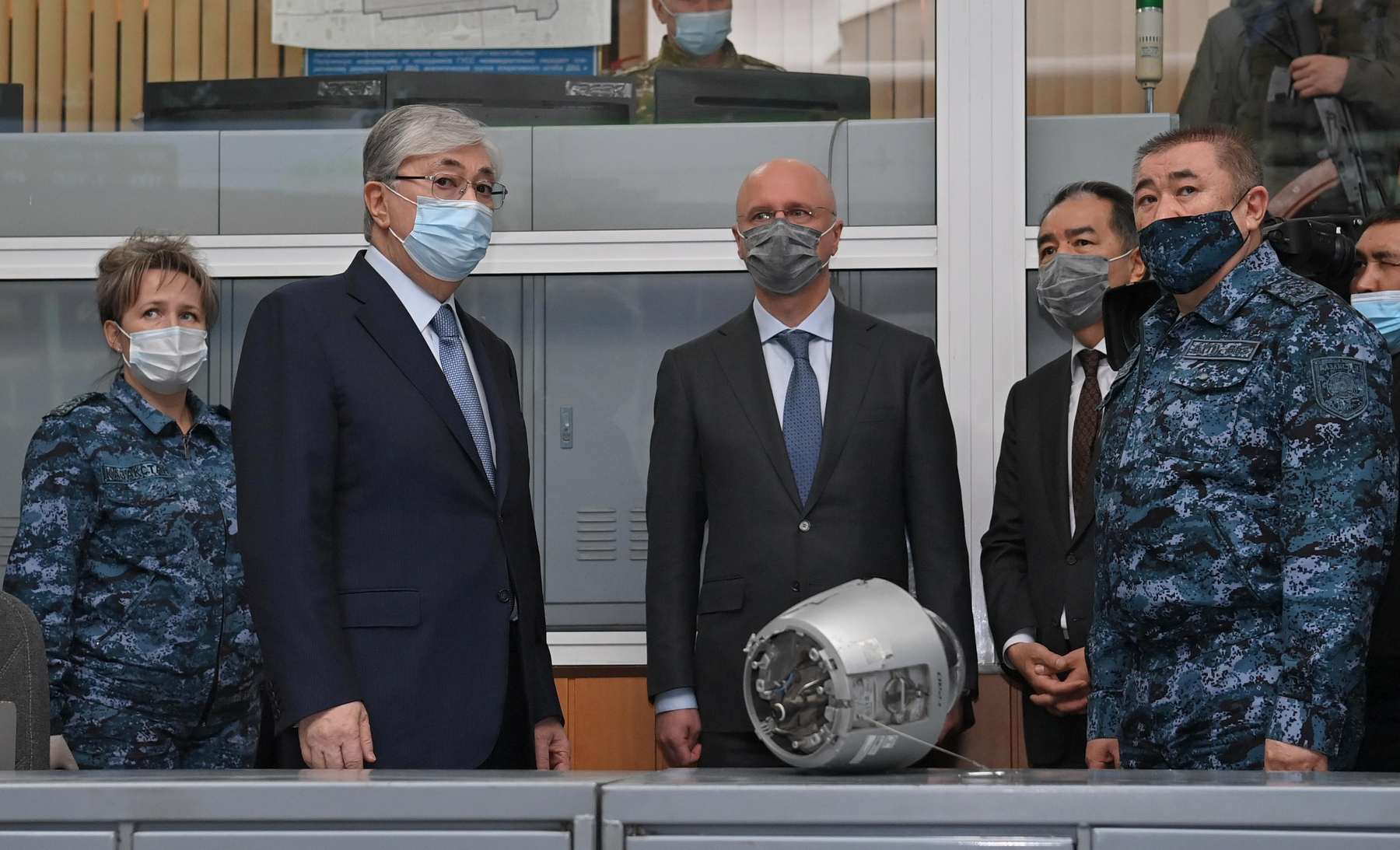

At present, one cannot easily predict how Kazakhstan’s leaders will respond to the discontent that won’t be going away any time soon now but the first reactions by President Tokayev and his supporters are moderately encouraging. In fact, during the first days of the protests the authorities acknowledged that poverty and regional inequalities should be actively combated. Later on, the President (who, of course, is not a poor person himself — his businesses and real estate have long been known, but they have never been compared with the wealth of the Nazarbayev family) condemned the excessive accumulation of wealth by businessmen who are close to politicians and officials, expressly mentioning Nazarbayev’s family. He acknowledged that many government agencies in the country are run like private commercial companies (e.g. the Customs Service, which has essentially legitimised smuggling from China); and finally ordered the government to speed up the development of an economic growth programme (a similar instruction, notably, was given exactly one year ago but was not implemented under the dyarchy prevailing at the time). Particularly noteworthy is the President’s initiative to revise the sovereign Samruk-Kazyna fund, which manages numerous large national companies, and to establish a public fund, provisionally named «For the People of Kazakhstan,» with the expectation that many large-scale enterprises will contribute to it.

Some experts have already described the recent events as a revision of the results of privatisation and have drawn parallels with Russia’s long-standing debate about the desirability of introducing the so-called «windfall tax» as an extra levy on oligarchs. However, I do not fully agree with this approach: unlike Russia, where major state-owned companies went into private hands in the second half of the 1990s under the then effective laws and regulations, the majority of similar corporations in Kazakhstan have remained state-owned, but have, until recently, been governed to serve private interests. The aim therefore is related to redistribution of influence rather than ownership, and an attempt at such reforms should be worrying mostly for the political classes of more authoritarian post-Soviet countries (Uzbekistan, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan or Azerbaijan) rather than Russian elites. What will now be put to a test in Kazakhstan is informal ownership arrangements and bureaucratic control over financial flows rather than ownership relations (challenging the latter may be fraught with consequences given the presence of foreign capital: which, if frightened off, would mean an end to the country’s policy of multivectorism).

At present, Kazakhstan is at complex economic crossroads: for three decades of independence, the country has built an efficient economic system relying on the commodities sector and governed by fairly modern bureaucrats. The extraction of natural resources grew faster here than anywhere else in the post-Soviet space, in parallel with the expansion of the financial sector, trade, logistics and online business. However, diversification remained an unattainable dream: while the mining sector accounted for 56% of exports in 1995, the figure reached 70.2% in 2020. Therefore, the second president faces the task of taking the economy to a higher level in an attempt to replicate what was achieved by, say, the Persian Gulf monarchies back in the late 1990s, as they were developing export-oriented industrial zones, offshore banking, construction and tourism, air transit, etc. Tokayev’s first steps in 2019−2020 evidenced his commitment to reforms, but the protracted «transit of power» effectively put an end to these plans.

Today, the task is not only to redistribute property and financial flows. It is no secret that Kazakhstan has looked closely to Asia throughout the years of its independence, looking for model strategies of economic growth. Hundreds of young managers received business education in China and Korea, and the Nazarbayev University is headed by Shigeo Katsu, a famous Japanese professor. The catching-up in Asia, as we know, always started under harsh authoritarianism and did not guarantee a rapid increase of living standards in the first decades. However, economic developments would subsequently call for the political regime to soften up or even to transition to a democratic system (with South Korea being the most notable example). Today’s Kazakhstan is reminiscent of Korea in the late 1970s, when not only economic but also political reforms were initiated after the assassination of President Park Chung-hee, who laid the foundations for the country’s «economic miracle.» The most important tasks for Kazakhstan at present are as follows: to reach social harmony and overcome the aftermath of the January riots with minimal damage to national unity; to carry out de-oligarchisation on a scale comparable to Korea’s fight against the chaebols; and to add a welfare component to the state, refocusing its efforts towards the fight against poverty and inequalities. If Astana can strike a balance between continuing Asian-style modernisation and implementing European-style social reforms, the progressive development of Kazakhstan that seriously stalled in the early 2010s may be successfully continued. The implementation of this scenario would not only become a breakthrough for Kazakhstan itself, but would also indicate the optimal direction of reforms for many other post-Soviet countries.

At the same time, Russia cannot ignore recent developments in Kazakhstan, but its perspective would be slightly different. In recent years, the Russian economy, with a structure very similar to that of Kazakhstan, has faced similar challenges. As of the end of 2021, Russia’s GDP exceeded the 2013 figure by merely 7.1%, which means that its growth has reached no more than one third of the Kazakhstan’s rate in the course of eight years. Citizens’ real disposable income has shrunk by almost 6.7%, even if we include the one-off payments, which are becoming ever more common but do not reflect any economic achievements. Finally, the gap in average income across Russia’s regions reaches a factor of 5.5, with a factor of 51 (sic!) in terms of Gross Regional Product per capita compared with 2.3 and 7.4, respectively, in Kazakhstan. Around 12.1% of Russia’s population are living below the poverty line (which, notably, is set at 12,654 roubles, or USD 166), which is three times as high as in Kazakhstan (24,011 tenge, or USD 54). In other words, economic inequalities in Russia are no less acute than in its neighbouring country, and there is not much chance that growth will accelerate, especially in the face of the very real prospect of new sanctions.

In my view, the only significant difference between Russia and Kazakhstan lies in the self-consciousness of the people and the identities of the two societies. In the Russian case, the Soviet and pre-revolutionary practices are commonly regarded as the benchmark, with clear bureaucratic hierarchies, class distinctions, the subordination of individuals to the state and the secondary importance of the nationality factor. In the Kazakhstan case, however, the issue of building a new nation is at stake, alongside building the unity of the people. This emerges as a much more significant consideration than the state structure and the system of governance, both of which have been built over the lifetime of most citizens, based on the rejection of the Soviet system. Therefore, I would argue that economic inequalities are much more dissonant with the nation-building rhetoric than is the case in Russia. The Russian society is less prone to economically-oriented upheaval, but even if we take this into account, the events in Kazakhstan give a lot of food for thought. To my mind, the economic and social parallels between Russia and Kazakhstan are even more significant than the political ones that are often pointed out.

The accelerated change in Kazakhstan has the potential to give full momentum to the main issue in the post-Soviet economic evolution: ownership rights are excessively dependent on informal arrangements with power elites, and assets are hard to control in an unstable political situation. If Kazakhstan’s economy were not based on such arrangements, a rebellion would be less likely since the loss of power would not deprive clans and groups of their economic position. In order for post-Soviet societies to transition to a truly non-Soviet reality, it is essential to formalise ownership relations, make financial flows transparent and create distinct social lift mechanisms in business, public administration and the non-profit sector. If Kazakhstan’s «big bang» turns out to give momentum to this process, the sacrifices made by the its people will not be in vain.