The Federal Service for Supervision of Communications, Information Technology and Mass Media (Roskomnadzor) started blocking access to the Telegram messaging app more than a month ago. Formally, the regulator was implementing a court decision in line with the so-called ‘Yarovaya law’ passed in 2016.

Yet the blocking of Telegram cannot be regarded as a successful blitzkrieg by the Russian state: It received negative media coverage, and triggered hundreds of memes ridiculing censorship. The civil confrontation reached its peak when a rally in Moscow drew thousands of participants. In late April, Roskomnadzor gave up on blacking out the messenger service’s IP addresses, since this had partially blocked the services of Google, Twitter, Facebook, Amazon, Viber and other major corporations. Currently, Roskomnadzor is blacklisting individual IP addresses, which does not drastically slow down Telegram. Despite a slight decrease in the number of Telegram users, views of major channels on the service are on the rise, according to TGstat.ru.

Who are Telegram’s users?

The formal reason for the crackdown was Telegram CEO Pavel Durov’s refusal to give the authorities access to users’ encrypted messages, which is technologically impossible without dramatically diluting security protocols.

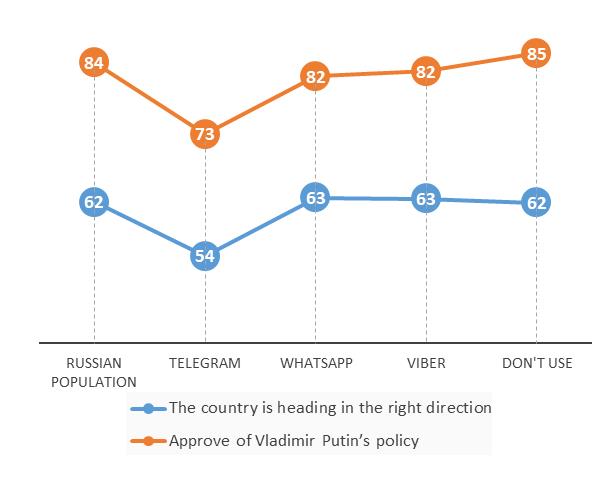

A much more interesting hypothesis is that the real reason for blocking the messenger is the independence and dynamism of Telegram’s channels. The Telegram community is based around reciprocal links and sectoral or ideological interrelations. Furthermore, it can be assumed that the channels attract a politicised audience that’s sceptical of the Russian authorities.

The reality is somewhat more complicated. Indeed, compared to other popular messaging apps, substantial differences in the level of support for the Russian authorities can be observed. This difference can be partially explained by the popularity of Telegram as an information platform as well as its specific socio-demographic profile: 65% of its adult users are aged 18 to 35, 10-15 percentage points more than in the case of other messaging apps.

Do you use instant messaging applications for mobile phones (mobile apps for calls and messages)? If yes, which one(s)?

The proportion of Putin critics among Telegram users is higher than in social media. We can say that Telegram unites critics of the government to the greatest extent, which is exemplified by the attitude to the Yarovaya law: 55% of Telegram users, versus approximately 35% of WhatsApp and Viber users, oppose the measure. Perhaps the attempts to block access to the service really are caused by its opposition potential. However, Russian officials’ view of reality in this case is based on an outdated understanding of the structure behind the power of information. The idea that media can simply be turned off is entrenched in the 20th century, when the hierarchy of relations between the media and consumers was absolutely vertical. In those days, it was enough to jam the radio signals of Voice of America or Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty, and restrict access to typewriters. The decentralized nature of the Internet and the minimal costs of connecting to the digital space mean censors have to change their tactics. Today, it is much more effective to attack with contradictory information, which obscures reality and the very idea of objectivity, as prophesied by Jean Baudrillard.

Roskomnadzor’s primitive blocking of Telegram is all more surprising given that the Russian state seems to have successfully mastered the art of deception. ‘Question more’ is the provocative, official slogan of the Russian television channel Russia Today broadcasting abroad, while alleged Russian interference in electoral processes has already become a hot topic for domestic political squabbles in the West.

From users to protesters

The authorities fear this lack of control over network mechanisms, especially after mass rallies in Moscow in April and May this year. It is noteworthy that the protests focused on defending the right of access to a familiar communication channel rather than political rights. Undoubtedly, general dissatisfaction with the situation in the country often drives rally participants, but this time, their demands were clear to the majority. The medium is the message here; it is not only (and not so much) the content that is perceived as dangerous by the authorities, but also the way it is presented in line with the expectations of the target group. Among social networks, YouTube viewers represent the most critical audience (comparable to Telegram users). This is not because YouTube is flooded with political information, but because opinion leaders have moved to the video service, having noticed a shift in the expectations of their target group for the way they present material. As the divide between society and the state deepens, the latter is losing touch with reality and control over communication mechanisms.

An expert survey conducted by the Levada Centre among the community of the All-Russia Civil Forum provides an insight into the sentiments of the elite. The problem of technological backwardness ranks second (32% of respondents) among the most serious challenges the country will face in 15-20 years. The positive scenario for the country’s future is primarily associated with the inevitable inclusion of Russia in the process of global economic integration and technological development. Even opposition-minded Russians, disappointed with political reforms, are optimistic about the technological progress of the media. The notion of the democratising role of technology is deeply rooted in public opinion. But in fact, it is not a black-and-white picture. On the one hand, the Twitter revolutions in Tunisia and Egypt proved the effectiveness of new communication technologies as a mobilising factor in the case of spontaneous protests. Durov’s input into the organisation of the April rally in Moscow only confirms this. On the other hand, the extent of state control over its subjects is tantamount to control over users. Whenever the state is not allowed to use administrative leverage (the way China does) to exert pressure on media corporations, officials have to make alliances with corporations that have access to personal data. The rules of fair play must be applied in order to build stable relations with private technology providers. Durov fled from Russia precisely because it was impossible to preserve his investment and his capital.

Telegram’s success in defending its interests in Russia was made possible primarily due to the intractability of the media moguls Google and Amazon, whose stance has won the respect of Russian liberals. Their policy is in line with the strategy of the Western world towards Russia: to reduce contacts with the state and support user privacy. In a broader context, Western corporations are perceived by ‘Westernised’ citizens as the embodiment of the progress of the West, as compared with the third-world countries that are trying to catch up with it. This is one more proof of the hypothesis that ‘the West will help us’. One cannot be sure that the approach of IT companies to cooperation with the Russian state will remain unchanged. The intervention of corporations has levelled the playing field among the conflicting parties, and we have therefore been left with a pure experiment that allows us to measure the endurance of Telegram as a symbol of technical and conceptual progress, and assess the backwardness of public administrators’ understanding of the modern world.