Since Moscow’s latest city-wide elections, an opposition electoral strategy has garnered praise. Labeled ‘Smart Voting’ (‘Umnoe Golosovanie’), the strategy creates a united list of opposition candidates in each city. It was spearheaded — amid repressive authoritarian conditions and a summer of public protests — by Russia’s most prominent opposition figure, Alexei Navalny. As Jan Matti Dollbaum writes, the goal was “concentrating all oppositional votes on the strongest contenders among the non-United Russia candidates [in each city district].”

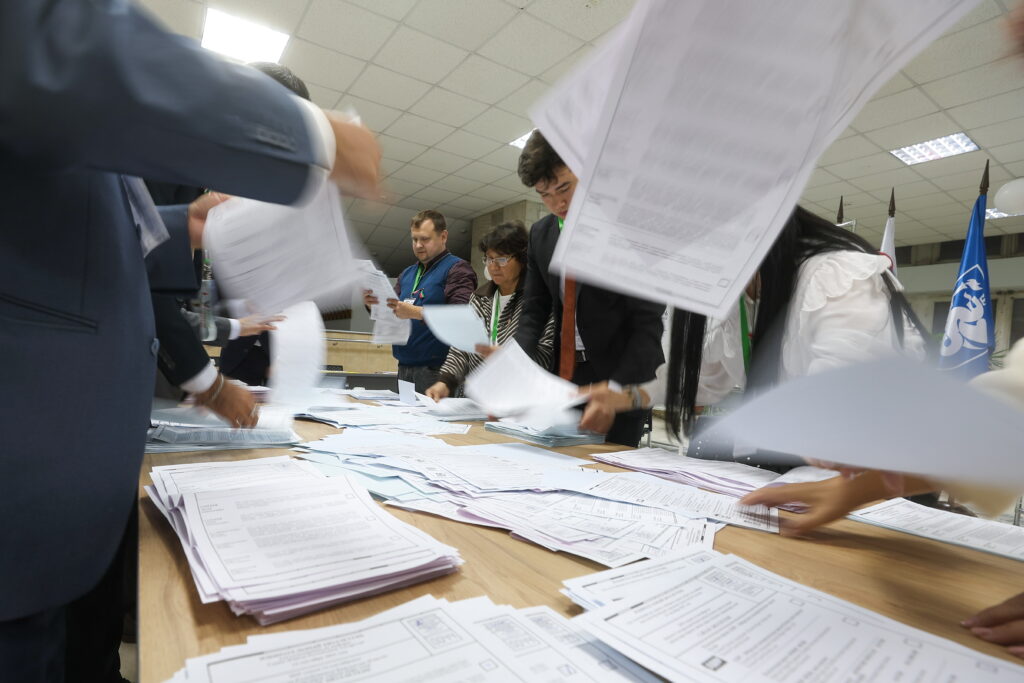

The results of this strategy were quite impressive. 20 out of 45 Moscow City Duma seats went to candidates from the list. There is debate about the gains. One credible estimate from Boris Ovchinnikov suggests at least 300,000 votes were swung. (That’s a claim supported by Stanislav Andreichuk, writing here for Riddle.)

These gains are modest. But consider this: district sizes are small and turnout is low. So modest gains matter. And it is no mean feat for a political opposition suffering from state crackdowns as recently as two months ago.

Many commentators see the strategy as being both surprisingly effective and a sign of Navalny’s enduring and central opposition role. Interpretations differ over what this all means. Writing in the Russian Analytical Digest, Yana Gorokhovskaia noted that the protest movement over the summer had been based in procedural demands for fairness. She suggested this was about a renewed focus on ways to change the system from within. For broader regime concerns, Regina Smyth of Indiana University suggested the elections confirm the brittleness of electoral control structures used by the Kremlin. Smyth reckons there is a need for the Kremlin to update them, or face further danger.

‘Smart Voting,’ Model 2011

But whatever comes in response to smart voting, few have touched on how it is not really anything so novel. Navalny tested a mechanically similar tactic in 2011. Without the snappy branding and less coordinated, it still brought pandemonium to parliamentary elections that year. It produced one of the most chaotic and pluralistic federal legislatures Russia had seen since the early 2000s. Throughout his campaign, Navalny specifically promoted a controversial tactic of “vote, and vote for anyone but United Russia” – one that would achieve surprising success in December of that year.

The Weighty Choice to Vote under Electoral Authoritarianism

It seems obvious that one should vote against the party (and regime) one dislikes. Yet there are in fact a variety of (mostly unenviable) choices available to discontented voters in authoritarian regimes. Perhaps the most notable is of course boycotting elections. This is to signal the illegitimacy of the process. It emphasizes the façade-like nature of an autocracy. Boycott is an active strategy. It had been called for by Russian opposition leaders in the past for the 2007 parliamentary and 2008 presidential elections, as well as the 2018 presidential elections.

Boycotting elections also can take a passive form. Voters don’t come out – not because of a political tactic, but because they don’t care. This version is often the one preferred by the regime itself, but results in the same outcome. Either way, turnout may be lower. But the strength of the opposition and its supporters are always absent.

Choosing to vote in authoritarian elections is less obvious as a tactic than the average Western voter might suspect. Boycotting an authoritarian vote at least gives an individual a feeling of not participating in an immoral system. The act of voting under autocracy can feel like giving consent to an illegitimate regime and can otherwise seem like a waste of time. Indeed, there is empirical support for denying a detested authoritarian regime legitimacy. Political scientist Ian O. Smith reckons non-democratic regimes experiencing long-term electoral boycotts by the political opposition are more likely to fall. Though that does not imply they will then democratize per se. So the Navalny-promoted “vote for anyone but United Russia” was controversial at the time among dedicated opposition leaders. Especially because the choice of non-United Russia parties to vote for was constrained.

Tactical Voting, 2011-Style

In Russia, Putin’s regime has regulated political parties on the ballot since the mid-2000s. Restrictive regulations on party registration is one tactic. Raising the electoral threshold to deny small parties is another. By 2011, the official party system fell to seven parties. and Only four got seats in parliament. Any opponents with parliamentary seats were called ‘systemic opposition.’ They were derisively seen as coopted and corrupted by the regime.

Voting for “anyone but United Russia” in 2011 meant that liberal or non-ideological but anti-regime voters were forced to choose among the old-school, gerontocratic Communist Party; the comically-named, xenophobic Liberal Democratic Party; and the nominal center-left party ‘A Just Russia, which’ had been created and promoted by the regime only a few years prior. All had significant baggage as corrupt, coopted, or unserious in the popular eye. None could be wholly trusted to act in the way an opposition-minded voter would like.

Even here, the outcome of Navalny’s 2011 electoral tactic was a success. United Russia failed to break 50% in the popular vote – and that was even factoring in high levels of recorded fraud and ballot stuffing. A quirk of the proportional representation system used at the time allowed United Russia deputies to scrape together a bare majority in the Duma. But it was a 15% drop in popular support and a loss of 77 seats. Turnout was 6% less than in the highly controlled 2007 parliamentary election, suggesting that the combination of opposition mobilization and broad regime dissatisfaction can have profound consequences in authoritarian elections. “Voting for anyone but United Russia” proved an enormous tactical success; it was the strongest showing of anti-Kremlin forces in the parliament since 2003.

Nothing comes easy in authoritarian regimes, of course. The fallout from the electoral debacle wound up with Putin back in the presidency three months later. Those empowered non-United Russia parties proved to hold their backbone for no more than two months; concerted (and expensive) regime efforts soon coopted them again. We cannot conclude that this sort tactic is any kind of golden bullet. But those two months of electoral shock also forced still-standing easing of party registration laws. It led to a return of modified gubernatorial elections and a closely-fought Moscow Mayoral election in 2013. That Mayoral election gave the opposition its best actual electoral results (for a real opposition candidate!) in over a decade.

Useless Elections Are Useless Until They Aren’t

The ‘Smart Voting’ tactical campaign that grew out of this past summer’s protest movement is a logical outgrowth of older, less sophisticated strategies by a political opposition confronting the problems of electoral authoritarianism. Boycott or passive disengagement may allow for a moral victory, or being able to live with yourself. But if pollsters can’t see there’s a large opposition to the regime that votes, it’s hard for you to convince yourself to publically express your own discontent – especially if you’re not a diehard activist, but just an average voter.

Those moments when the Russian political opposition got its act together have also produced the most notable institutional results. Hopes for democratization may not have followed. But capturing political positions within the system, however unsatisfying, has produced concrete results. It has further galvanized protest movements and provided key political skills to new generations of opposition politicians and activists.

Furthermore, each time this tactic has been used, it has benefited the systemic opposition like the Communist Party and the LDPR. These parties make their living coopted by the regime. Yet they also see clear electoral results when they are able to capitalize on anti-regime sentiment. Regional elections elsewhere in Khabarovsk are the perfect example – where a protest vote that installed an LDPR governor has now been matched by an overwhelming LDPR legislative majority this September. As the geriatric leaders of the systemic opposition approach the end of their careers, the incentives to capitalize on their selling point as the least evil choice will only grow.

In the meantime, Alexei Navalny continues his hold on the non-systemic opposition. He has bona fides as an effective politician amidst a field of coopted, inconsequential or frustrated activists and party hacks. Predicting an individual’s success is a fraught business; but Navalny and his organization are at the cutting edge of successful opposition tactics almost a decade into his political career.

“Vote for anyone but United Russia” has been transformed – funnily enough by the same opposition actor as nearly a decade ago – from a simple choice to vote for anything but the autocratic enemy, to a coordinated vote for an officially recognized least of all evils. Now it is a targeted list on the internet, relying on an informational education campaign to get around the lack of party labels given to candidates that is the latest innovation in the Russian electoral authoritarian regime. The Moscow city election in September shows this tactic’s promise as well as its obvious limitation, and once more proves that participation is usually the better, if imperfect, choice for voters in authoritarian regimes.