Fifty-eight regional and federal elections took place on 9 September, 2018. Russian citizens voted for State Duma deputies, governors, members of regional legislative assemblies and mayors. The aim of this article is to discuss the results and analyse what was different from previous elections. Has the Communist Party of the Russian Federation (CPRF) really taken the lead?

The election to regional parliaments

This year saw turnout reaching record lows. Official turnout for the regional legislative assembly election in Zabaykalsky Krai was 22%. The previous record low, in 2013, was about 25% in Arkhangelsk and Irkutsk Oblasts. In those previous worst performers there were at least a few modest improvements. In 2018, turnout in Irkutsk Oblast reached 26%. In the Arkhangelsk Oblast, it got to 29%. Like in Irkutsk and Arkhangelsk Oblasts, turnout improved slightly in the Republic of Khakassia (from 37.8% to 41.8%) and Vladimir Oblast (from 28.5% to 33%). What explains these improvements? One reason is these regions voted both for governors and for members of regional parliaments. Still, turnout was low. That is despite unpopular reforms and innovations to boost turnout such as a ‘mobile voter’ system.

Besides low turnout, Irkutsk Oblast and Zabaykalsky Krai did not overwhelmingly support United Russia (UR). Votes in favour of UR, the CPRF and Liberal Democratic Party of Russia (LDPR) were quite evenly distributed in Zabaykalsky Krai. The CPRF was ahead of UR in the Irkutsk Oblast. UR did not enjoy immense support in the Republic of Khakassia’s legislative election, either: the CPRF won (31%) and the LDPR’s results (21%) are close to those of UR (25.5%). This may undermine the thesis that UR benefits from a low turnout.

Although mainstream parties managed to outstrip UR in some of the regions on party lists, UR is still the leader in first-past-the-post (FPTP) voting constituencies there: UR beat the CPRF by 5 seats in FPTP constituencies (12 versus 7) in the Republic of Khakassia. The number of seats is equally distributed between the CPRF and UR in FPTP constituencies in the Irkutsk Oblast.

FPTP constituencies are often UR’s for the taking. Although the CPRF can sometimes pose a threat to UR in single-member constituencies, mainstream parties rarely win a seat under FPTP voting. For instance, UR lost the 2011 regional election in some regions. That included the Republic of Karelia, Tver, Orenburg, Amur, Novgorod and Kirov Oblasts. But UR bounced back in parliamentary elections. For example, the ruling party won only 38% of votes based on the lists versus 83% in single-member constituencies in Perm Krai in 2011. The same goes for Novgorod Oblast and Krasnoyarsk Krai.

A similar situation arises in UR heartlands. Many experts noted a nearly 20 percentage point fall of UR support on party lists in Bashkiria in 2018. It was 76% in 2013 and 58.3% in 2018. But, few experts noted that UR’s result in single-member constituencies in Bashkiria improved (39 seats out of 55 in 2013 versus 44 in 2018).

Thus, the question arises: why is UR losing votes in some of the regions? Experts mention internal conflicts of regional elites as one reason. But these regions had already demonstrated high volatility in the past. New parties garnered strong support in such regions as the Republic of Khakassia, Zabaykalsky Krai and Irkutsk Oblast in regional elections in 2011-2014. 20% voted for new parties altogether in each of these regions that year. In the 2018 election, mainstream parties drew more attention from voters due to a significant drop in the number of new parties. Generally speaking, party systems in undemocratic regimes exhibit high volatility or inconsistency of voter choices. The average number of parties is larger than in democratic countries (5.6 parties in undemocratic regimes compared to 3.45 in democratic countries). So, this volatility does not necessarily reflect disappointment in the ruling party.

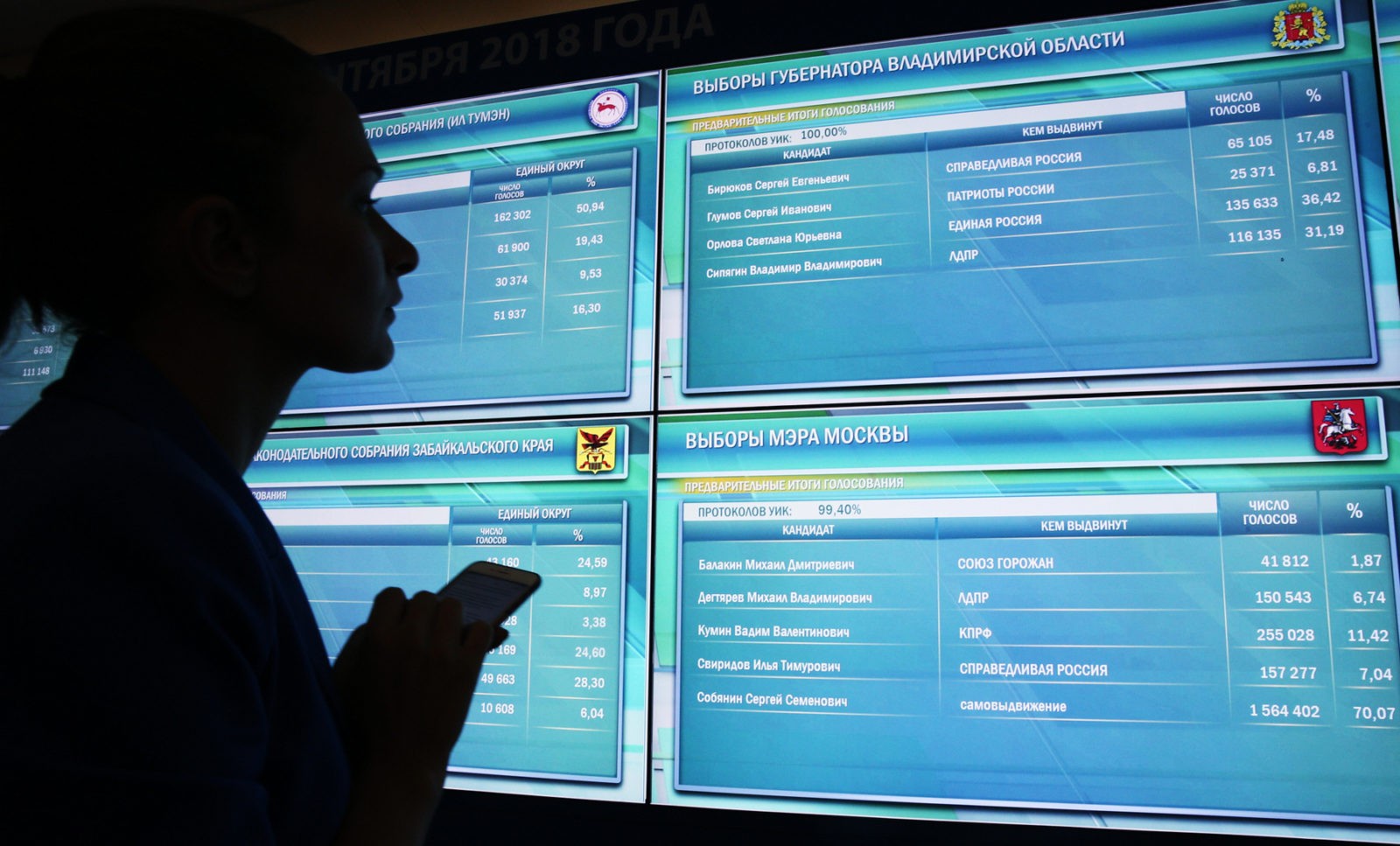

Gubernatorial elections

Sunday’s election results mean that for the first time in years, there will be a second round of the gubernatorial election in four regions of Russia. UR candidates will compete with CPRF candidates in Primorsky Krai and the Republic of Khakassia, and with LDPR candidates in Khabarovsk Krai and the Vladimir Oblast. The situation is unusual. Direct elections of governors were reintroduced as late as in 2011. and the first direct election was held in 2012. On the other hand, such an outcome of the first round of the election is not unexpected. The CPRF has a strong presence at the municipal level both in Khakassia and Primorsky Krai. The party is therefore capable of clearing the municipal threshold without the help of the ruling party. So, the CPRF does not have to seek UR’s approval of its nominee.

Although the media are writing about an unprecedented rise in the CPRF’s popularity (Meduza), the actual reason for its electoral success might be a municipal filter. Non-mainstream parties with no significant support in municipal parliaments failed to collect the required number of signatures to nominate their candidate. To succeed, they have to seek help from the ruling party.

Four regions with runoffs in the gubernatorial election do not yet mean a trend. It does not imply liberalisation or a wider decline in UR’s popularity. Non-UR candidates have been heads of regions (in Irkutsk, Omsk, Oryol and Smolensk Oblasts, for example). Additionally, in 2015, a CPRF candidate outstripped the then interim governor representing UR in the second round of the gubernatorial election in Irkutsk Oblast. In 2014, UR did not nominate a candidate for governor in Oryol Oblast. As a result, the CPRF candidate won the first round with 89% of votes. Has UR weakened since then?

The lack of turmoil in 18 regions is much more interesting. In 14 of them, the governors had been dismissed before the end of their tenure and interim governors were appointed by the President of the Russian Federation in their place. All the interims won with a landslide. None of the dismissed governors was re-elected.

By-election to the State Duma

Public discourse concentrates on an insignificant victory of the CPRF in the latest regional election. But that is a distraction from the following facts. On September 9, during the by-election to the State Duma, five out of seven seats were taken by UR, one by the CPRF and one by the LDPR (the latter two in constituencies with no UR candidate). This reflects the outlook for the future more than predictions of a fall in UR’s popularity and the CPRF taking over.

What to expect?

It is difficult to identify any trends or patterns. Frequent rule changes mean the success of any party can turn to dust. Rules on the election of governors, or party registration rules have shifted to and fro. Almost every election is held under fresh conditions.

That means one can expect new amendments to election laws as a matter of course. The focus will not be mainstream parties, but the regions where UR lost or nearly lost. Amendments might include tightening the municipal filter to prevent runoffs. There might also be a further transition to first-past-the-post-voting in regions where such a system would prove a serious advantage for UR over all other parties. There could also be a further loosening of requirements for new parties to ensure the outflow of votes from mainstream parties.