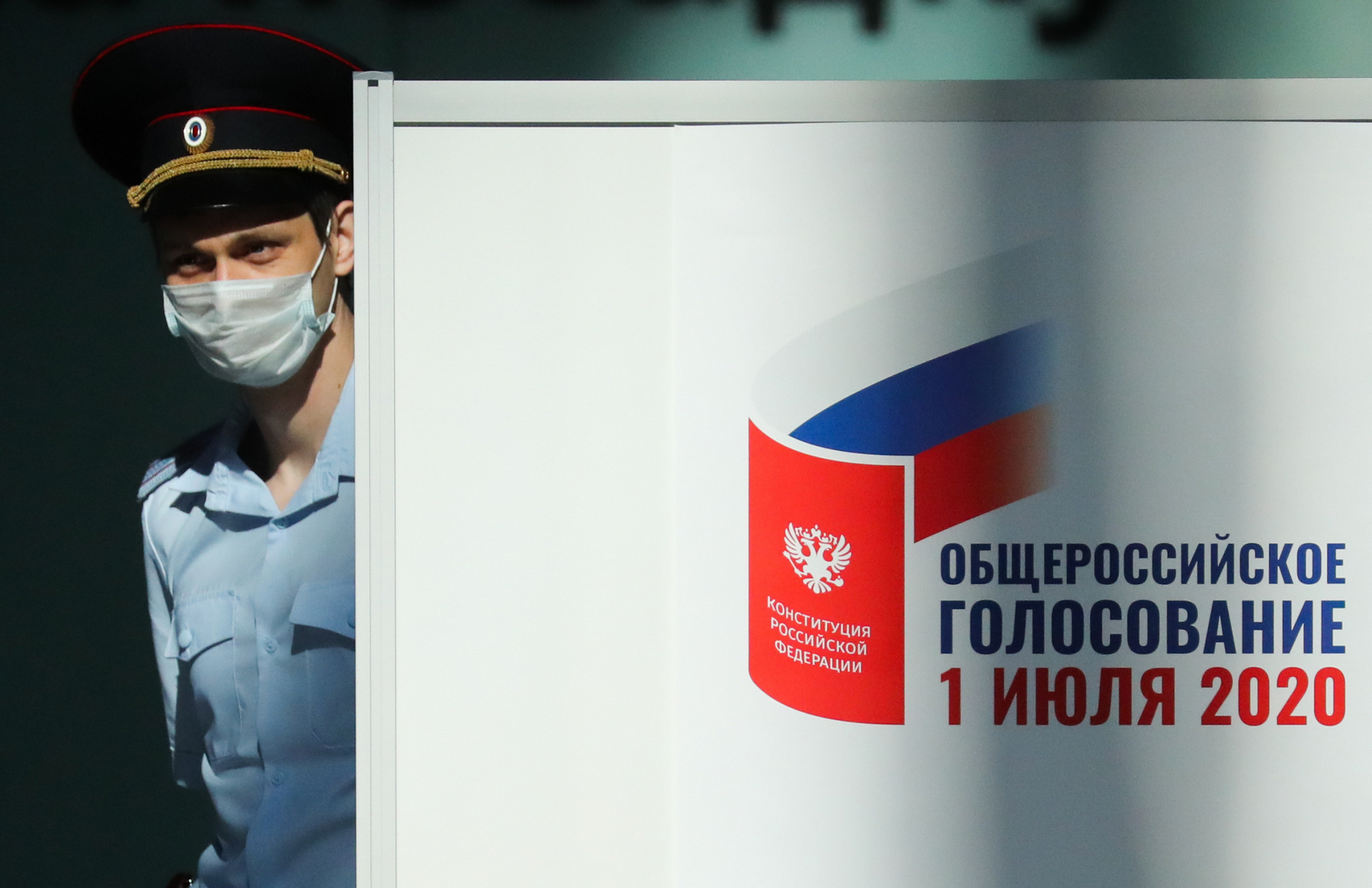

In his annual address to the Federal Assembly on January 15, Vladimir Putin proposed constitutional amendments that amount to his largest attempt thus far of revising Russia’s fundamental law. Two months later, on March 14, 2020, the presidential bill titled ‘On improving the regulation of certain issues related to the organisation and functioning of public authority’ was published. Before that, the bill had passed through the Federal Assembly. It was approved by all regional parliaments within two days. The constitutional reform will culminate in a popular vote, now set for July 1.

On December 20, 2012, at a press conference, a journalist from the Izvestia newspaper asked Putin whether he thought that ‘the personalist authoritarian regime’ built in the 2000s was viable. His answer points to a plausible interpretation of the 2020 reform and the popular vote meant to legitimise it. First, Putin disagreed that the system he built was authoritarian; he noted he had observed term limits and did not stand for election in 2008. Secondly, he stated: ‘If I believed that a totalitarian or authoritarian system was the most preferable, I would have simply changed the constitution, it would have been relatively easy to do. It doesn’t even require any sort of national vote, it is enough to reach a decision in the parliament.’

As follows from Putin’s words, the national vote is pointless in the case of constitutional amendments. Of all the amendments, which enlarge the volume of the fundamental law by 40%, the one that resets Putin’s time as president to zero is the only one that really matters.

A popular vote at the president’s whim

As stipulated in art. 3, para. 3 of the Constitution, the power of the people comes through referenda and free elections. Neither the constitution nor the Russian legal system provides for such an institution as a popular vote. More importantly, amendments to chapters 3-8, as stipulated in art. 136 of the Constitution, are adopted by a special procedure. They come into force after approval by at least two-thirds of regional parliaments. The amendments had undergone the required procedure by March 14. Since the Constitution has precedence over other Russian legal acts (art. 15, para. 1), the conclusion from this simple syllogism is obvious; the constitutional amendments have already entered into force. This was acknowledged by CEC head Ella Pamfilova on March 20 when she emphasised that the amendments were voted on only with the president’s will.

Besides having no binding force, the popular vote is going to happen under rules that are easy to abuse. Early voting outside the premises of election commissions will happen for the first time. Remote e-voting will be conducted in the Nizhny Novgorod Oblast and Moscow — a precinct area of almost 10 million voters. Many election commissions will be operating with breaks ‘for the preventive disinfectant treatment of voting premises’. At the same time, only observers representing public chambers and media outlets will be able to monitor the vote. Media representatives will have to get special accreditation, either from the Russian Central Election Commission or though regional election commissions.

The key amendment on resetting Putin’s term-limit clock

The main task of the constitutional reform is to guarantee Putin unlimited power beyond 2024, the year his second consecutive presidential term expires. The Kremlin has entertained various scenarios for preserving Putin’s power, and seems to have decided on resetting the term limit. Article 81, para. 3.1 of the amended constitution gives Putin the right to run for the presidency in 2024 and 2030.

The extension of the presidential term with a removal of term limits is a simple and popular scenario in the post-Soviet space. The term-limit reset is familiar presidents of Azerbaijan (Ilham Aliyev), Belarus (Alexander Lukashenko), Kazakhstan (Nursultan Nazarbayev), Kyrgyzstan (Askar Akayev), Tajikistan (Emomali Rahmon), Turkmenistan (Saparmurat Niyazov) and Uzbekistan (Islam Karimov). Globally, from 1945-2017, there have been 94 ‘extenders’.

In the case of Russia, resetting presidential term limits contradicts the spirit of the constitution. According to Article 3, para. 4, ‘No one may usurp power in the Russian Federation’. It is true that the reset itself does not automatically make Putin head of state until 2036. However, it is inevitable. Russia’s presidential elections are held under conditions of controlled competition with use of the administrative resource, voter coercion and vote-count rigging. To expect Putin to lose or give up power under these conditions is like betting that water will flow up a mountain. The reset also violates the principle of power alternation established in Article 81, para. 3, which imposes presidential term limits.

What about the other amendments?

Like the term-limit reset, important amendments to the fundamental law include the expansion of the head of state’s powers at the expense of the Federal Assembly, government and judiciary. The president himself does not represent any of these branches, as before.

Other amendments introduce ambiguous concepts and institutions. For example, what is ‘the state-forming people’ (art. 68, para. 1)? What are ‘traditional family values’ (art. 114, para. 1c)? What is ‘public authority’? (art. 71d), ‘a single system of public authority’ (art. 132, para. 3) and ‘the foundations of public order’ (art. 125, para. 5.1b)? What is the purpose of ‘federal territories’ (art. 67, para. 1)? What exactly is the State Council tasked with?

Some of the constitutional amendments contradict other constitutional provisions. Art. 67, para. 2.1. which deems calls for the alienation of a territory unconstitutional, and art. 67.1, para. 3 which bans the ‘diminishing of the importance of the nation’s heroic deed in defence of its Fatherland’ are in contradiction with art. 29, which guarantees the freedom of thought and speech. Art. 67.1, para. 2 (‘ancestors have passed on ideals and faith in God’) contradicts art. 14, para. 1 about a secular state. The revised version of art. 75 as well as art. 125, para. 5.1b are in contradiction with art. 15, para. 4 which stipulates the supremacy of international agreements over national law. Art. 131, para. 1.1. legalises the incorporation of local self-government into the system of state authorities, which contradicts art. 12.

All the social amendments are pure populism. Their content duplicates the norms already present in Russian laws or the constitution. For example, the norm on the annual indexation of pensions is within the Law ‘On the state pension system of the Russian Federation’ (art. 25), while a minimum monthly wage of no less than the minimum subsistence level is provided for by the Labour Code (art. 133). The same goes for so-called ‘patriotic’ amendments, including the provision that ‘the Russian Federation ensures protection of its sovereignty and territorial integrity’, which is a repetition of art. 4, para. 3 of the constitution. There is also a new provision on the Russian Federation ‘as the legal successor of the USSR’, which can also be found in, for example, the preamble to the Law ‘On state policy of the Russian Federation with regard to compatriots living abroad’. The social and patriotic amendments are meant to divert citizens’ attention from resetting Putin’s time as president to zero and the new structure of power emerging in the country. They also serve the purpose of state propaganda to promote the amendments among the citizenry.

Russia’s personalist electoral dictatorship

The popular vote on the amendments is a redundant PR campaign that costs Putin a great deal. The campaign was interrupted by the coronavirus pandemic, which exposed the authorities’ unwillingness to help citizens and economy to the extent of what the USA and Western Europe have offered to their population and businesses. The lack of real state aid and the late anti-crisis measures resulted in a drop of Putin’s approval rating from 69% in February to 59% in May. There is no doubt that the outcome of the plebiscite is what Putin cares about right now. Citizens who take part in the popular vote will also pay a price. The number of coronavirus cases is on the rise in many regions.

Together with enhanced powers, the term limit reset means the system of checks and balances will no longer exist even on paper. The process of the country’s transformation into a personalist electoral dictatorship can be regarded as completed. And there is more bad news. Now that the road to a lifetime presidency is cleared for Putin (he will be 83 by the end of his second extra term in 2036), he will not retreat. If his popularity continues to decline, Putin might have to scale up repression to achieve results in 2024 and 2030.