The appeal court’s verdict in the high-profile fraud case against the former deputy prime minister of the Perm region, Elena Lopaeva, was recently published (the verdict itself was delivered in April). This trial is notable for calling into question the outcome of the 2018 Russian presidential election — according to witnesses and Lopaeva herself, there were so many financial irregularities during Putin’s campaign that he should have been disqualified from running.

In reality, this is just the tip of the iceberg: the financing of political parties (especially the ruling party) and administrative candidates is largely hidden. Moreover, the financing of many state and municipal projects is also shrouded in secrecy, leading not only to corruption but also to the strengthening of the power vertical.

How the system of financing political parties and election campaigns in Russia is organized from a legal point of view

The financing of political parties and election campaigns is regulated by Russian law in a fairly detailed manner. In theory, this is necessary to provide a level playing field for candidates and to ensure that ideas and substantive arguments, rather than parties, play a decisive role in elections. The problem is that the enforcement of these rules, like everything else in the current Russian legal system, is highly selective.

By law, political parties are subject to strict financial restrictions: the sum total of donations may not exceed just over 4 billion rubles per year, and the maximum amount of donations from a single legal entity may not exceed 43.3 million rubles per year. Donations from citizens, membership and entrance fees, income from commercial activities and loans are also possible, but these sources are usually of minor importance (only the «United Russia» party actively uses interest-free loans from its regular donors, thus partially circumventing the restrictions). In addition, there is annual state funding for parties that received more than 3 per cent of the vote in the last Duma elections (152 robles per vote received) and one-off state funding if a party’s nominated presidential candidate receives more than 3 per cent of the vote.

These rules should have increased competition between parties, but in reality they have had the opposite effect. The «United Russia”‘s income exceeds the total income of all other political parties by 1.8 times. The five parliamentary parties account for over 94 per cent of total income. State funding also contributes to this inequality, with almost 60 per cent of the budget going to the ruling «United Russia» party. This includes the cost of maintaining parliamentary assistants, offices in the regions and travelling around the country, all of which also affects the financial stability of the parties, as they often employ members of the party apparatus as assistants and use the offices for party needs.

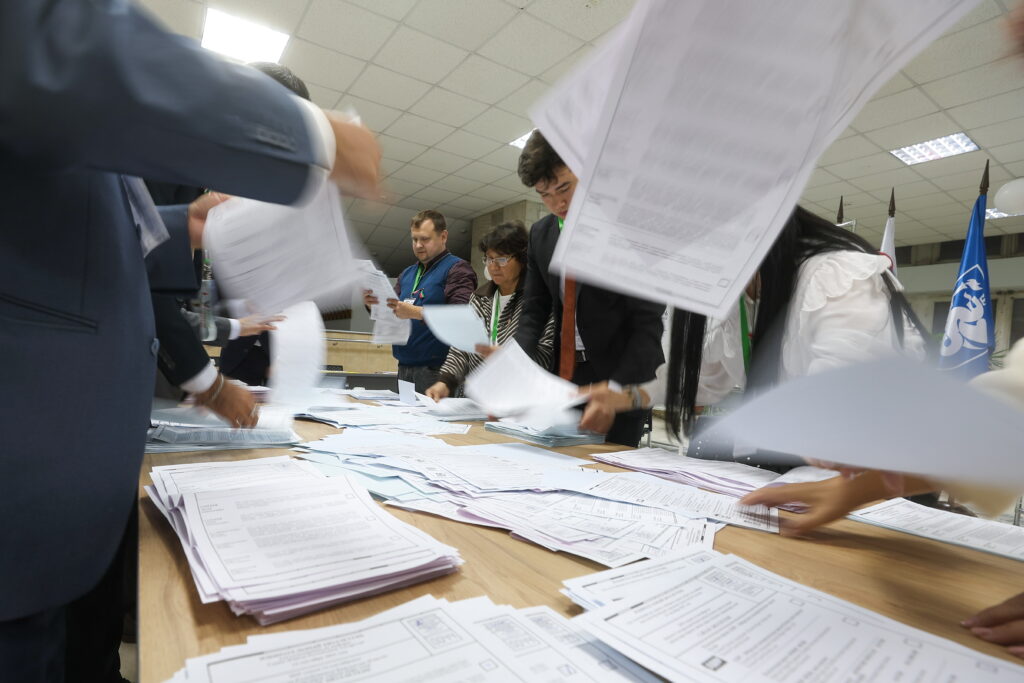

Campaign finance rules are structured in a similar way: there are limits on the size of donations and limits on the size of expenditure from the campaign fund. All campaign expenditure must be channeled through the campaign fund. If an election reveals a financial violation of more than 5 per cent of the spending limit, the candidate or party must be disqualified from the election. For presidential elections, the spending limit is set at 400 million rubles. Accordingly, in case of a violation of more than 20 million rubles, a candidate loses his or her registration.

What did the court find?

A former high-ranking official of the Perm region, Elena Lopaeva, was accused of fraud. According to the investigation, in 2017−2018, she stole 67.7 million rubles from the charity foundation «Assistance — 21st Century». However, Lopaeva herself says that she spent this money on the election campaign (the context clearly points to Putin’s campaign, although his name is not mentioned in the court’s decision). The evidence mentioned in the verdict and the testimony of witnesses support this version of events. Candidate Putin’s financial statements for 2018 do not show any such legal entity, and the donation exceeds the permitted amount. Thus, the violation in the Perm region alone is more than three times higher than the five per cent threshold, after which the candidate should be disqualified from running.

This fact alone would be enough to cause a sensation, but the details show that the situation is even worse.

The «Assistance — 21st Century» foundation worked as follows. Large companies (e.g. LUKOIL Perm) paid contributions to the fund and received tax benefits in return. The fund was managed by the deputy chairwoman of the Perm Region government, who personally coordinated spending with the governor. According to the prosecutor’s office, from 2014 to 2019 the «Assistance — 21st Century» foundation received 4.8 billion rubles in donations. In general, the total turnover of the fund reached 22.8 billion rubles (just to compare: the total revenue part of the budget of the Perm Region for these six years was 616 billion rubles, and in 2018 — 115.6 billion rubles).

Thus, a rather large amount of tax revenues did not go to the regional budget, but to a special «purse» the strings of which were not controlled by the Accounts Chamber and other supervisory bodies. The money from this purse was arbitrarily disposed of by officials of the regional government (according to Lopaeva, they were following the instructions of Governor Maxim Reshetnikov, who now works as Russia’s Minister of Economic Development).

Some of this money seems to have been used to meet the personal needs of the governor and his inner circle: it was said at court hearings that these funds were used to buy an iron, bathroom scales, a hookah, groceries, sneakers, a children’s slide, and to pay bills at expensive restaurants. Another part of the money was spent on election campaigns — presidential and gubernatorial. Lopaeva’s appeal states that the testimony «about the expenditure of 67,000,000 rubles on the organization of the election campaign in 2018 is confirmed by statements, expense cash vouchers, testimony of witnesses I., S1., B1., audio recordings. To pay for the work of agitators, brigadiers, political technologists, she (Lopaeva — editor’s note) transferred her personal money to the foundation. Her election activities were recognized with a letter of thanks», and the decision to finance the 2018 election campaign in the Perm Region from the resources of the foundations was made personally by the Governor Maxim Reshetnikov. This necessity arose because «Moscow did not allocate «United Russia» a budget and the governor had to «make the best of it «’ (which makes it clear that we are talking about Vladimir Putin’s campaign).

According to witnesses, the Russian presidential election was financed at the expense of the foundation. The project was called «Perm Region — Forward! New Time». However, a significant part of the contracts for this project turned out to be fictitious: they were not executed, and the money was collected and used to pay off debts. Lopaeva says (and witnesses partly confirm) that this money was used to pay for the work of agitators, political technologists and other pre-election services.

How widespread is this scheme?

The Perm case is by no means unique. In 2018, for example, the former vice-governor of Chelyabinsk and spin-doctor Nikolay Sandakov was sentenced to five and a half years in a penal colony. The published verdict also states that the «United Russia» party had an unofficial fund from which additional payments were made for election events. The fund was created from various sources, including money donated by candidates for MPs. The deputy governor managed the fund’s money. Requests for the necessary amount were made to him and he issued the money, which was used to pay for the work done. The money was kept in a safe in the office and used to pay technologists, sociologists, campaigners and for tea parties of the team.

In 2019, the high-profile «Gaizer affair» — named after the governor of the Komi Republic — ended with convictions. The verdict also mentions the «shadow treasury», to which large companies contributed (for example, the energy company KES-Holding contributed 100−300 million rubles a year, the network company Komienergo — 15−60 million a year, the Mondi Syktyvkar timber complex — 40−50 million a year, and the Syktyvkar distillery — half a million a month). According to the written testimony of Konstantin Romadanov, the deputy prime minister of Komi, the resource giants — LUKOIL, ROSNEFT, Zarubezhneft and Severstal — were involved in the elections with the help of the Russian presidential administration. Money was transferred in the form and manner most convenient to the donor — in cash and in kind. For example, the Austrian company Mondi sponsored the Football Federation of the Republic of Komi, which used the money to give loans to «designated parties».

Such funds existed (and continue to exist) in all regions. The public financial statements of Vladimir Putin’s 2024 election campaign show that the candidate’s fund received more than 400 million rubles, and the donors were various regional cooperation and development funds closely linked to the «United Russia» party. There is no public information on the financial sources of these funds. They are the main official donors to the «United Russia» party and many administrative candidates, but they may also accumulate other funds managed by representatives of the party or the respective administrations.

The lack of transparency of these funds not only fuels corruption, but also the ‘power vertical’

The problem with these funds is not limited to the misappropriation of the money in them for the personal interests of those who control them or the creation of unequal conditions in elections.

The same funds are distributed arbitrarily to support communities. One of the witnesses in the Perm case said that «the directions of spending and the objects of financing were determined by the governor together with the government of the Perm Region and the municipalities. Extra-budgetary funds were channeled within the framework of social investments on the basis of three-, four- or five-party agreements, and the responsibility for using the funds lay with the constituent entity of the Russian Federation. On the part of „No. 2“, there was no audit of the use of charitable funds by the foundation or the regional government. The responsibility for the proper use of the funds allocated to the Foundation under the Agreement rested with its management.»

For example, even municipal aid was not allocated according to the bureaucratic procedures laid down in the law, but arbitrarily by decision of the governor and the government. This means that the top officials themselves decided who should receive money and who should not, without any competitive procedures. Thanks to this system of distribution, it is possible to reward the heads of municipalities (for example, for correct election results) or, on the contrary, to punish those who are too lax.

In such a system, there are no instruments of control over the money and the process of decision-making on its distribution, not only for the public, but even for the state authorities. And this system continues to operate throughout the country.