In 2012, researchers at Cambridge University discovered a serious security vulnerability — a hidden backdoor — in a Chinese-manufactured chip used by the US military. This flaw could allow external parties to disable or reprogram the chip even with security protections in place. The chip was reportedly found in critical systems, including weapons, nuclear facilities, and public transport infrastructure. Some experts later questioned whether the backdoor was intentional or merely an accidental feature, but the incident underscored serious concerns about supply chain security for sensitive hardware.

Later that year, a US Senate Armed Services Committee investigation revealed counterfeit electronic parts from China in key military systems, such as the Air Force’s largest cargo plane, Special Operations helicopters, and a Navy surveillance plane. China had allegedly replicated US microchips using e-waste, compromised them, and sold them back to the United States. The committee found over one million suspect counterfeit parts across 1,800 cases, and reported that the Chinese government denied visas to staff investigating the issue.

The Hudson Institute warns that compromised microchips expose critical defense systems to cyber infiltration, deliberate malfunction, or sabotage. In a crisis, such vulnerabilities could be exploited by the Chinese government to disable or manipulate military assets. The threat is especially grave because compromised chips can be inserted deep within supply chains and integrated into complex systems, creating hidden vulnerabilities that might lie dormant until activated.

Military-grade chips vs COTS

Military-grade microchips are specialised components designed to meet stringent standards for durability, reliability, and security in extreme environments such as high radiation, temperature, and vibration. These chips undergo rigorous testing and certification to ensure performance in critical defence applications. Their export is tightly controlled by national regimes to prevent their proliferation to adversaries. Military-grade chips are supposed to be manufactured in secure facilities with strict supply chain oversight to reduce the risk of tampering or compromise.

Commercial Off-The-Shelf (COTS) components refer to readily available hardware or software products designed for general commercial use rather than specialised military or aerospace applications. While COTS parts offer cost efficiency and ease of procurement, they typically lack the ruggedness, security, and reliability standards required for mission-critical defence systems. Their use introduces potential vulnerabilities, especially when sourced from foreign suppliers, as they may be susceptible to tampering or hidden backdoors.

Nevertheless, COTS components are increasingly used in modern weapons systems due to their cost-effectiveness, availability, and technological advancement. This makes them attractive for integration into a wide range of military platforms, particularly in areas like communication systems, navigation modules, and unmanned aerial vehicles. For example, Russia’s Orlan-10 drones have been found to contain COTS microchips and modules sourced from commercial supply chains.

In fast-moving or resource-constrained conflicts, such as the ongoing war in Ukraine, the reliance on COTS has increased due to limited access to specialised components.

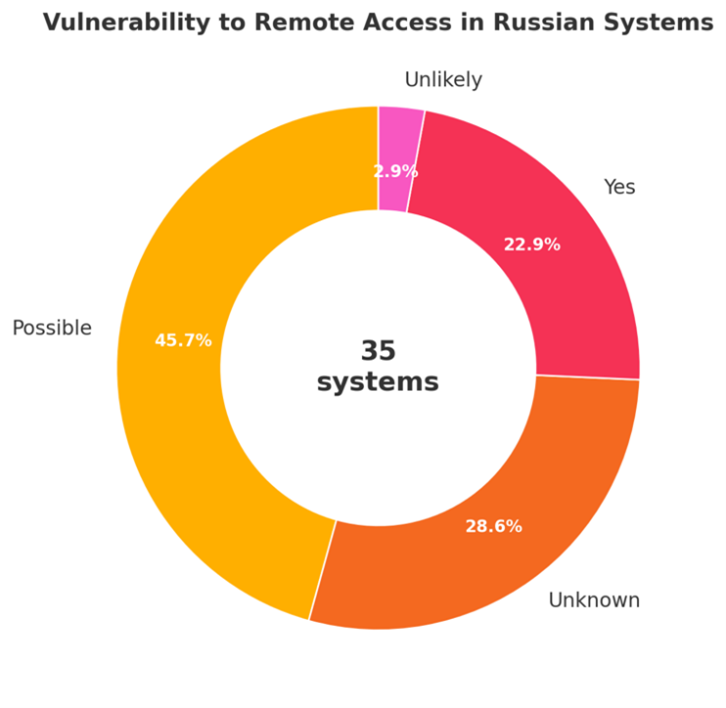

The chart below illustrates an assessment of 35 Russian military and dual-use platforms incorporating Chinese-made COTS microelectronics. Of these, 45.7% were assessed as possibly vulnerable to remote access, reflecting likely exposure through insecure firmware, compromised hardware, or exploitable communication protocols. An additional 22.9% were confirmed to contain components previously identified as remotely accessible or compromised. In contrast, only 2.9% were deemed unlikely to be vulnerable, while 28.6% remain unclassified due to insufficient technical data. The findings suggest that a significant proportion of Russian systems carry embedded cyber risks stemming from their reliance on unverified or foreign-sourced electronics.

Russian tech dependence

The war in Ukraine did not create Russia’s technological weaknesses — it exposed and deepened them. Long before the invasion, Russia struggled with chronic underinvestment in research and development, failed nanotechnology ambitions, and increasing reliance on China. Western sanctions and the breakdown of ties with European suppliers only accelerated this dependency.

In 2011, Moscow launched Rusnano but despite high-level support, by 2016, it was near bankruptcy amid corruption scandals. And Russia’s technological dependence has shifted decisively towards China. Between 2013 and 2018, EU tech imports declined sharply, while China’s share grew. Domestic R&D stagnated below one percent of GDP well before the war, limiting Russia’s strategic autonomy. By 2023, Moscow was locked into dependence on China, losing its ability to balance between East and West.

Russia’s hardware sector has suffered further since 2022, and now the intelligence reportedly circumvents sanctions by routing chip purchases through third countries, while military units scavenge chips from civilian appliances.

According to the Carnegie Institute, China and Hong Kong accounted for nearly 90% of all global chip exports to Russia between March and December 2022.

A separate analysis by the KSE Institute, based on recovered Russian battlefield equipment, indicates a more nuanced picture: between January and October 2023, China was responsible for 47% of production and 66% of origin points for battlefield goods. While this still highlights China’s central role as both a manufacturing base and transit hub, it suggests a slightly reduced share compared to earlier chip-specific data.

Chinese firms like Huawei, for example, exploited this gap to the maximum, expanding in Russia despite espionage concerns and sanctions violations. Huawei — the same company investigated and penalised by the US government for espionage risks, sanctions violations, intellectual property theft, and deception in its global operations, including the illegal sale of surveillance-enabling telecommunications equipment to Iran and North Korea — has made significant inroads in Russia by exploiting the Kremlin’s lack of alternative suppliers.

Application of COTS in Russian weapons

The use of Chinese COTS components in Russian weapons systems has increased significantly since the onset of Western sanctions following the 2014 annexation of Crimea and intensified after Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in 2022.

Super-weapons

Kinzhal missile, for example, shares significant architectural and subsystem similarities with the Iskander-M ballistic missile, which has been documented by Ukrainian and Western investigators to contain Chinese-origin microchips. These include components marked with Chinese characters and prefixes, and some reportedly originating from Nanjing-based manufacturers.

Orlan-10 UAV

Russian Orlan-10 unmanned aerial vehicles, for example, have been found to contain Chinese-manufactured microchips, particularly within their navigation and control systems. Analysis of downed Orlan-10 drones revealed components such as the HC4060 2H7A201 and STC 12LE5A32S2 35i — both produced in China — embedded in the GPS tracker module. These microchips play a critical role in the drone’s navigation functions, including its interface with Russia’s GLONASS satellite system.

In theory, both the HC4060 2H7A201 and the STC 12LE5A32S2 35i microchips could be compromised, although the likelihood and potential impact vary significantly between the two.

Garpiya-3 (G3)

On September 25, 2024 Reuters reported that Russia has set up a weapons development programme in China aimed at producing long-range attack drones. According to two sources from a European intelligence agency and documents reviewed by Reuters, the Russian defence firm IEMZ Kupol — a subsidiary of the state-owned conglomerate Almaz-Antey — has developed and conducted flight tests of a new drone model, the Garpiya-3 (G3), in China with the assistance of local specialists. One of the documents, a report from Kupol to the Russian defence ministry, outlines the project’s progress earlier this year.

DLE (Dual-Mode Low Emissions) aircraft engines

DLE engines typically referring to modern gas turbine engines with advanced low-emission combustion systems — do incorporate electronic components, including microchips, as part of their design. These electronics are essential for precise engine control, emissions management, and system diagnostics.

A key feature of modern DLE engines is the integration of a Full Authority Digital Engine Control (FADEC) system. FADEC units rely on microprocessors, memory chips, and various electronic components to continuously monitor and regulate critical engine parameters such as fuel flow, temperature, pressure, and rotational speed. This ensures optimal engine performance while keeping emissions within strict limits. All DLE engines are equipped with networks of sensors and embedded electronics to support real-time diagnostics and health monitoring. Since DLE combustion requires finely tuned control of air-fuel mixtures and combustion stages, microchips and digital logic are necessary to manage these functions accurately and efficiently. And all of them come from China.

What can it possibly mean?

Although China and Russia maintain close relations, they are not bound by a formal military or political alliance. From a strictly legal standpoint, there is nothing to prevent China from asserting control over Russia or its weaponry.

Declaring a «friendship without limits» is characteristic of communist political language. Anthropological linguistics — the study of cultural and linguistic habits — shows that such expressions are common in communist and post-communist discourse, often serving more as ideological signalling than concrete commitment. They did not prevent Russia from invading Georgia in 2008, nor did they deter its invasion of «brotherly» Ukraine in 2022. Similarly, China’s rhetoric of unity did not stop it from retaking control over Xinjiang region.

«Intelligence and Security Committee of Parliament — China» report, published by the UK Parliament’s Intelligence and Security Committee, examines in depth how China systematically seeks to gather intelligence across a vast range of sectors and subjects. It would be highly naïve to assume that China is not actively seeking detailed knowledge about Russia. But knowledge on weapons systems and their locations holds unique value for any state. And technically, those chips serve as a window into such sensitive information.

Russia may have created a significant vulnerability for itself, and how China might exploit it is open to interpretation.