The events that largely defined Russian politics in 2021 happened the year before. The poisoning of Alexei Navalny. The presidential elections in Belarus with the protests that followed. The outbreak of the coronavirus pandemic. Much of the Kremlin’s bandwidth in 2021 was taken up with responding to these 2020 crises.

Election year and victory at all costs

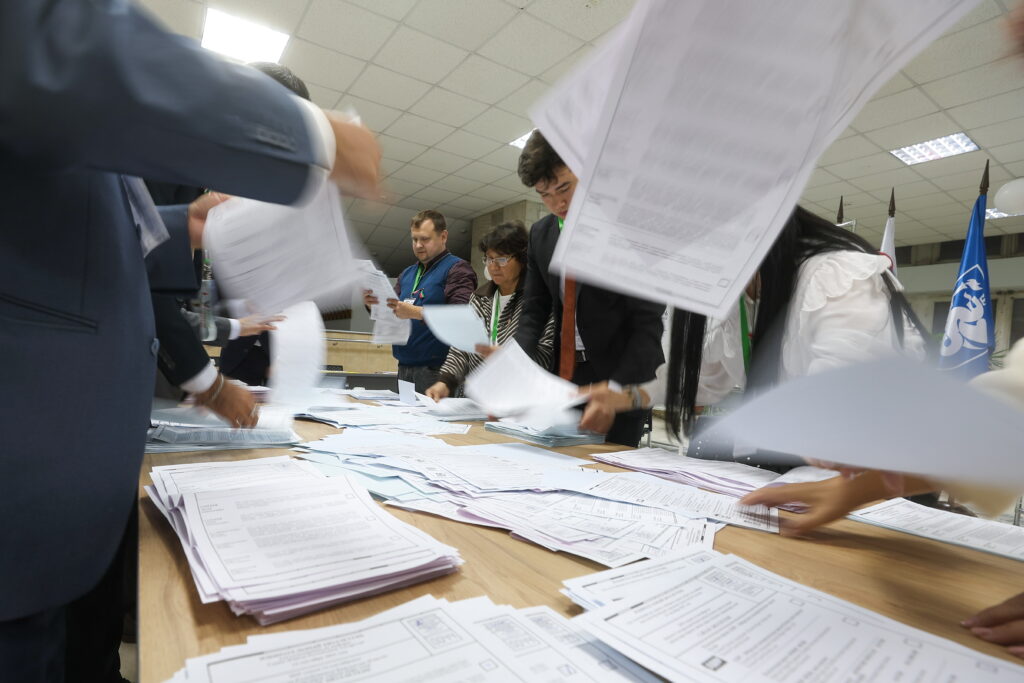

Electorally, 2021 has been a year of elections to the State Duma. The backdrop to these was stark. The economy has not been in the best shape; the country is tired of the pandemic. So the key task of the authorities has been to try by all possible means to ensure the victory of United Russia. By this logic, Russia saw the arrest of Navalny and destruction of his networks. This highlighted how a new raft of repressive laws adopted in 2020 could be put to use. Broadly, that has meant war on independent media outlets and a redoubled hunt for political activists.

United Russia got its victory. Even before the official election results were announced, Kremlin officials celebrated it. Jubilant volunteers danced in the autumn rain in front of the party headquarters. Moscow’s mayor Sergei Sobyanin was so emotional that he could not even find words to express his delight. “Putin! Putin! Putin! Victory!” – he shouted into the microphone. Even though it was in Moscow where the victory of United Russia in single-mandate constituencies was in question. The announcement of the results of remote electronic voting was delayed for a very long time, leading skeptics to well-grounded suspicions.

Elections are always a crisis. This thesis is true even for systems like the Russian one, where the procedure is fully or almost completely controlled by the executive branch. Surprises are not entirely out of the question and the same was true here.

Arresting Navalny

The political year did not start right away. It really began on January 17, when Alexei Navalny returned to Russia after treatment in Berlin. He was detained as soon as he got Sheremetyevo airport. On January 19, his comrades-in-arms posted an investigation film “A Palace for Putin” on YouTube. It was the most watched Russian-language video on this platform in 2021 with over 120 million views. After that, there were protests demanding the release of Navalny. Various strategies of intimidating the dissent were used. First, people were beaten in the streets, using not only truncheons, but also stun guns (it is a rather new innovation for Russia). Protestors were detained by thousands before the rallies were allowed to go ahead quite peacefully again. But that was a trick. The authorities had turned to CCTV camera footage to identify those present and arrest them a few days later.

The result, almost a year on: Navalny looks set to stay in prison for the foreseeable. New criminal cases have been opened against him. His networks have been declared extremist and banned. His most prominent associates have emigrated. The rest will have to wait to see if the state has enough patience and reach to get to them abroad. The first arrest has already taken place – a former employee of Navalny from Ufa, Lilia Chanysheva.

If the “calendar logic of election year” worked, we could have assumed that after a United Russia triumph, repressions would recede. This is not the case, since Chanysheva was detained after the elections. The Ministry of Justice is methodically replenishing the register of foreign media agents, there are already more than a hundred positions. New criminal cases are being investigated against Navalny and his supporters. The Prosecutor General’s Office is demanding the elimination of the country’s oldest human rights organization, Memorial, which was previously included in the register of NGO-foreign agents. Court hearings are underway, and Memorial’s chances of survival are low.

A range of video bloggers, rappers or other online personalities who many would consider compliant to the regime have become victims of repression. Of these social media crackdowns, there stands out the “buttocks war” – a series of criminal cases against young people who risked taking frivolous photos against the backdrop of Orthodox churches. In the Chelyabinsk Region, they are going to judge a homeless person who dried socks on the Eternal Flame at the memorial to those killed in the Great Patriotic War for the “rehabilitation of Nazism”; his case is under the personal control of the head of the Investigative Committee, Alexander Bastrykin.

Reverberating tensions in Belarus

A major driver for this type of anxiety in the Kremlin has been the deterioration of events in Belarus. Hundreds of thousands of people took to the streets to protest unfair elections there. Lukashenka had enough repressive power (and Russian loans, of course) to retain power. But the Kremlin clearly learned from its mistakes, destroying in advance the possibility of any “assembly points” for discontent in Russia itself. After all, Belarus has also shown that not only recognized political leaders can lead people to protest. Svetlana Tikhanovskaya was definitely not such a leader before the start of the election campaign and was not going to become one. It made the Kremlin proceed with attempting to prevent any Russian Tikhanovskaya arising.

The very ideology of the late Putinism – the ideology of confrontation with Europe and the United States under the slogan of a “struggle for sovereignty” – does not imply the possibility of a real opposition in the country, the possibility of criticizing the authorities, the ability to appeal to the voter.

The regime is consistently working – and will continue to work – to eliminate such possibilities. So far, with success. Jail time for Navalny and the destruction of his structures significantly weakened the Russian opposition (which, to tell the truth, was not particularly strong before). But this does not mean that political activists or independent media should now expect some relief. Everything is exactly the opposite. They are still the number one target, but there are fewer areas where people who avoid participation in political life will feel safe. As the space of real politics is destroyed, the regime will politicize literally everything and punish for any uncontrolled activity. There will be no thaw.

Pandemic panic

There is also a pandemic that cannot be ignored: people are dying. Even according to official statistics, Russia has been losing over a thousand people a day in recent months. The virus in Russia is strangely docile when politics demands. For example, it very much moderated its activity before the elections, so as not to irritate the electorate with restrictions. And it perked up almost immediately after the closure of the polling stations. But besides statistics that can de doctored, there are crowded hospitals and unpopular decisions. Here, the Kremlin faced a problem it did not expect: the indignation of a significant part of the population less from the pandemic than its clumsy response.

Russians have failed to get behind the vaccination campaign (despite the fact that one of the Russian vaccines, Sputnik V, was swiftly rolled out, apparently quite effective, and even free for citizens). Instead, Russians buy fake vaccination certificates. They create chatrooms where they share the wildest conspiracies. Sometimes they even go out to protest rallies against lockdowns. It is not the regulars of opposition rallies that come out here, but people who are otherwise indifferent to politics and consider themselves loyal. They often write down appeals to the president asking for help, to protect them from covid-fascism on the ground. Among the most notable fighters against the “digital concentration camp” are show business figures, who it is ridiculous to suspect of opposing the authorities.

The reasons for this “quiet revolt” are not fully understood. But officials are treading with care. In speeches, they avoid triggering terms like “lockdowns”; they shy away from talking about “compulsory vaccination” (although in the regions mandatory vaccination for certain categories of citizens has long been a fact). This protest is horizontal. It has no obvious leaders. It cannot be the work of “foreign agents” and insidious Americans.

See these conspiracies as a symptom. The authorities are destroying any channels for dialogue and trust building debate with society. The logical result is the sugary picture of universal support is unplugged from reality. The authorities do not know what to expect from the population, and there is nowhere to find out. Fighting invented or insignificant political threats remains a strong suit for the Kremlin, and this war will continue into 2022.

That said, this regime is generally not tailored to work with real internal crises.

And this is perhaps the main result of the year: the real threat to the regime is not political activists; the real threat is the apolitical population whose protest activity falls out of the usual patterns. What the authorities took for years to be nationwide support was in fact nationwide indifference. In conditions of a relatively tolerable life and even an increase in its level, it is easy to demonstrate loyalty, one can even sincerely rejoice in territorial acquisitions, hypersonic missiles and how cleverly our diplomats have hoodwinked Europeans or Americans. But now the nationwide indifference is being transformed into discontent. Anything can act as an irritant, and the Kremlin clearly has no ready-made answers to this challenge. Most likely, within the framework of the political system formed by Putin, such answers cannot even be formulated.