Few now doubt that Moscow’s incumbent mayor, Sergei Sobyanin, will still be in his post after Election Day this September. These are elections in name only; there is no real contest to speak of. The results themselves will say very little. The only thing up for debate is the scale of Sobyanin’s victory over his rivals, if that’s what these also-rans can claim to be called.

Even so, there will be points of interest during the campaign, which are worth monitoring closely.

Moscow’s curse

Before we mention those, it is worth explaining why and how the upcoming elections will be devoid of political conflict. This cannot be stressed enough, as offensive as that may sound to people with opposition views in Russia. Today’s Russia is centripetal — the political agenda is set by the authorities, the authorities are in the Kremlin and the Kremlin is in Moscow. The Kremlin runs the show in Moscow more than anywhere else. This is the curse of the capital: and it is only possible to upset the apple cart here in one way — turning the city elections into an event that has a bearing on the entire Federation.

Such an experience, by the way, exists: it was the mayoral election of 2013, where Alexey Navalny took part. It was clear beforehand that the opposition candidate would not under any circumstances win an election in the main city of the country, but that was not so important. Navalny managed to frame the campaign in a very simple system of coordinates: main denouncer of state corruption against a dull bureaucrat, a symbol of today’s power in Russia.

Navalny challenged not only the authorities of Moscow but confronted a vision of an old, corrupt Russia of Vladimir Putin, with a vision of a new Russia — a new Russia that rejects those old rotten rules of the game. Even the official result of Navalny — 27.24% of the vote — was the biggest success of any non-systemic opposition for the entire tenure of Putin’s rule.

So such experience exists. But there’s no candidate like Navalny this time. Last time, Navalny was allowed out of Kirov pretrial detention center; he was granted the required number of Moscow MP signatures of support in order to pass the municipal filter. It was rumored that this “miracle” was given a green light from Vyacheslav Volodin, the main man responsible for domestic politics at the Presidential Administration at that time, who disliked Sobyanin and wanted to give him a bit of a tough time. Now, of course, the situation is different – Navalny was barred from participation in the presidential race this past election. Still, he managed to run an impressive campaign despite the ban. Long story short, participating in a mayoral election would be a step down for him.

Other opposition candidates lack the necessary authority, charisma or influence to match that of Navalny. This campaign would be only a mayoral race; it would be hardly possible to make it a federal question that would ignite wider interest and swell turnout. Moreover, all of the opposition challengers would be compared to the success of Navalny, which in its turn would play out against them.

Eternal split

This time there would be no one opposition candidate. Potential challengers have not been able to agree on how to do the primaries, and now the election has effectively turned into a parade of personal ambitions. Ilya Yashin registered as a self-nominated candidate. Dmitry Gudkov became a candidate from the “Civil Initiative” party. This is a registered party, founded in 2013 by the former Minister of Economy of the Russian Federation, Andrei Nechaev that has not achieved any notable successes whatsoever. Now the “Civil Initiative” is waiting for reforms —on its foundations, the “Party of Changes” of Gudkov and Ksenia Sobchak is being created. The founding congress of the “Party of Changes” was announced for June 23, and there are enough unpleasant rumors about the project going around already. Everyone remembers Sobchak’s participation in the presidential elections, where she acted, perhaps not on the direct orders of the Kremlin, but certainly in favor of the Kremlin, as a “legal representative” of unpopular liberals (that is, she acted as a self-appointed “deputy” of Navalny, justifying his ban from that race). It is possible that the creation of a new party is a step in the same direction: the argument about the unpopularity of opposition ideas in elections of any level of power will only benefit the Kremlin with any “Party of Changes” low scores proving the case.

Signatures and World Cup Woes

A detail worth noting is how Gudkov, as a candidate from a registered party, will not need to collect voter signatures. But Yashin will. To participate in elections, the self-nominee Yashin needs 36 thousand signatures. After that, both need to pass the municipal filter — getting more than a hundred signatures of municipal deputies from 110 Moscow districts. The relative success of the opposition in the election of city deputies last year, over which there was a lot of rejoicing, does not solve this task: There are simply not enough opposition deputies.

Thus, it’s all in the hands of United Russia deputies, who of course support the acting mayor. In other words, Sergei Sobyanin will decide which of the opponents to admit before the elections and who to leave out.

This, by the way, is not the only obstacle for the opposition candidates: they need to start collecting signatures right now, but Moscow is the city where the World Cup is held, and for the time of the World Cup any political agitation is prohibited by a special presidential decree.

Another peculiarity of the upcoming elections is the Yabloko party that decided, by demonstrating openness to new trends, to hold its own primaries in order to decide on the candidate for the mayoral elections. The head of the Tver district of Moscow, Yakov Yakubovich, won, and immediately declared that he would not participate in the elections. Yakubovich suggested that the leadership of the party nominates the head of the Moscow branch Sergei Mitrokhin, who was already trying to become mayor in 2013 (the result was a failure – less than 4%). The scandal in the party still lasts, it is asserted that the explanatory talks with Yakubovich were conducted by the head of the party Grigory Yavlinsky himself, but the main result has already been achieved: the very idea of the primaries has been discredited.

The mayoral carnival

The pyrotechnics will prove compelling and distracting as Sobyanin goes for victory, that will make his campaign seem like a premature victory lap. He has new metro stations, new stadiums for the World Cup and even a rebuilding program going for him. The scandals that accompanied that large-scale rebuilding project have long subsided.

There’s no irony here – all of it is quite useful for the biggest town in the country.

What you have against him are the anti-corruption investigation into horrendous embezzlements that occurred during these major constructions and renovation. This of course angers the Muscovites, but doesn’t make drive them to do too much about it. Moscow is still way too rich and prosperous, despite the troubles that Russia in general has been going through. All the publications about corruption are flashes in the pan; no criminal charges are being made as a result; no firings or official inquiries. But the new metro stations stay open and this satisfies the majority of the city.

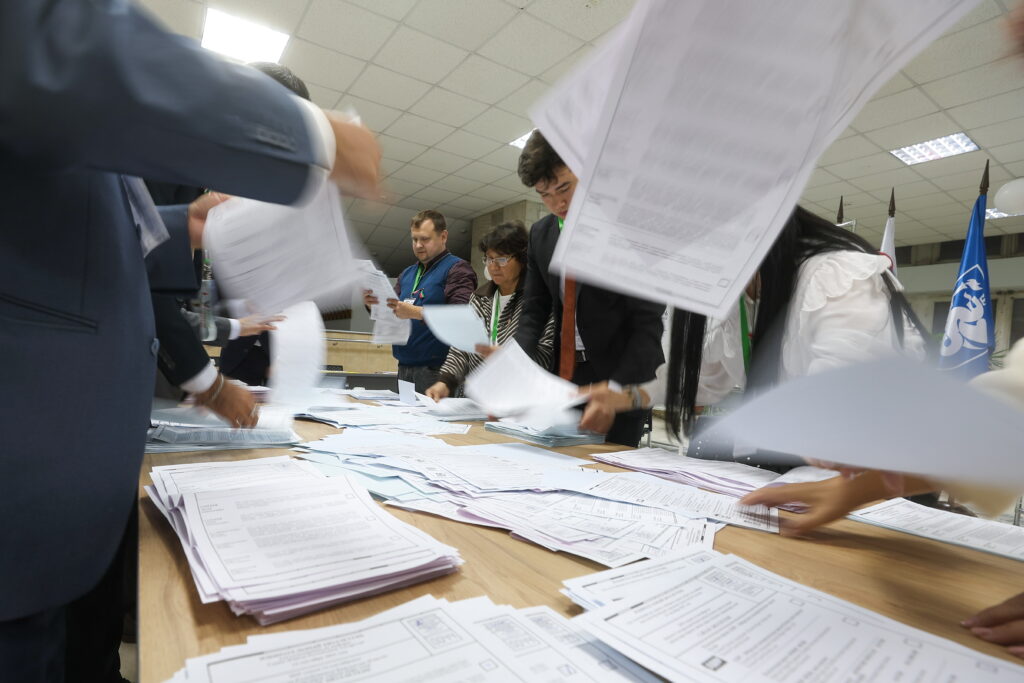

A new city law will also play into Sobyanin’s hands. It promises access to polling stations near suburban areas, which will allow summer residents on a September Sunday not have to return to Moscow in order to cast their vote. First, the core of summer residents are the hyper-loyal and disciplined pensioners, who are the main support base of the authorities (they will not even worry about raised retirement age since they are already retired). And secondly, it’s close to impossible to control how elections take place there. A working group has already been set up under the auspices of the Moscow City Executive Committee, which is figuring out aspects of the law’s implementation.

And here is an important moment that allows us to grasp the essence of Sobyanin’s campaign. We saw this already in the presidential election of 2017, when Russians were allowed to vote without absentee certificates at the place of their actual stay. Sobyanin is taking these sorts of tactics straight from Putin’s presidential campaign. Putin was a self-nominee, same goes for Sobyanin; the president relied on volunteers — the mayor already reports on thousands of volunteers in the newly opened election headquarters. The president managed without a pre-election program, and the mayor relies on a list of achievements instead of political declarations for what will come next.

Sobyanin even has his own personality cult heated by dozens of city newspapers and paid bloggers. There are even TV sets in the subway cars, where, as already explained by the Moscow elections committee, it will be possible to demonstrate political views. One needs not to guess who the state-owned “Moscow-24” channel might be lobbying for.

This is a new way to demonstrate maximum loyalty to the national leader: Putin sets the model for elections, which do not even look like elections, but something like an oath of allegiance. Sobyanin’s model repeats it in details but a Moscow-wide scale.