Russia’s media ecosystem has changed dramatically since February 24. A law penalizing the spread of intentionally «fake» news about the military (No. 32 — FZ) was swiftly passed by parliament in early March; it has been used ever since to crank up political pressure on media outlets and bloggers. The law «On control over the activities of persons being under foreign influence» (No. 255-FZ) adopted in June and coming into force in December is written with similarly coercive aims in mind. Even before any of this came into force, the Ministry of Justice had already been busy releasing and updating weekly lists of foreign agents. Leading media outlets that offered an alternative agenda, meanwhile, have been forced to close or leave the country.

The advertising market, an important source of funding not only for commercial but also for state-run media, has been similarly hard hit. The Association of Communication Agencies of Russia (ACAR) has recorded a 6% year-on-year drop in the advertising market in local currency in the first half of 2022, which was relatively successful compared to the pandemic year 2020. However, specific data for individual market segments was not released given «the limited quantity and reduced quality of information sources». Yet the downward trend in the market facing the departure of major foreign brands and the revision of marketing budgets by Russian companies is obvious. According to the Russian Association for Electronic Communications (RAEC), online advertising will have shrunk by half by year end, while the digital content market will have shrunk by 60%. Such an advertising drought will leave the media more dependent on public funds. At the same time, privately owned, regional and niche media face a harsh winter.

In this backdrop, what is happening to Russian media consumers and TV audiences? We shall answer this by drawing on the available data from research institutions.

Morbid screen staring

The importance of the Internet as a source information on society and politics used by the Russian public is growing steadily. Even so, television still clings on as the dominant news medium. According to the Levada Center, the percentage of people who see television as the primary source of news has been decreasing steadily since June 2013, while online sources of information have risen in relevance. Indicators of trust towards various sources of information match this, albeit with an important twist: the level of trust towards television news increased in April 2022 compared to January 2021, while the level of trust towards the Internet decreased.

Indeed, the overall level of trust in domestic media (print media, radio and television) recorded at the end of August 2022 was the highest ever observed and recorded by the Levada Center since its data collection began, with 41% (which is 5% more than in 2021) of the respondents claiming they trust Russian media. The previous highest figure — 38% – was recorded back in 1989, shortly after the Levada Center embarked on its monitoring research.

There are three main TV channels that have traditionally served as key sources of news: Channel One, Rossia-1 and NTV. They account for approximately one third of the total volume of television time in Russia. Since the outbreak of Russia’s war against Ukraine on February 24, the events related to what the Kremlin euphemistically calls a «special operation» have become the centerpiece of the agenda, eclipsing all other news items. Some entertainment and infotainment programs were removed from the broadcast schedule. For example, Vladimir Pozner’s eponymous evening show in which he interviewed public figures and Ivan Urgant’s late night talk-show «Evening Urgant» were both taken off-air by Channel One; so was Andrey Malakhov’s show «Live with Andrey Malakhov», which was re-launched at the end of September, on Rossia-1as «Malakhov». This curbed TV appearances for members of the creative class, many of whom were critical of the events.

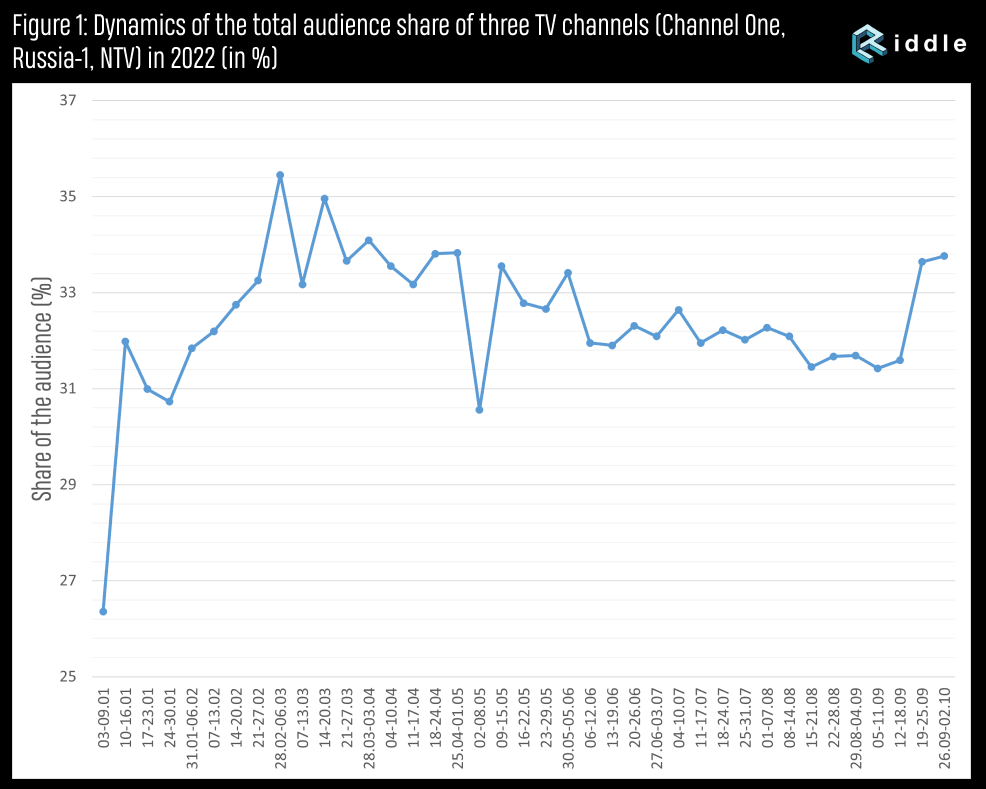

The graph below (see fig.1) illustrates the weekly dynamics of the total audience share for the three top channels between the beginning of the year and early October. The audience share is calculated as the average percentage of individuals who watch a given TV channel out of the total number of individuals watching any television channel. For example, if at a certain point in time the audience share of channel N equals 5%, it means that every twentieth of the total number of viewers is watching channel N, while the remaining 95% are watching some other channel.

«The top three TV channels are most successful in attracting viewers during the periods of heightened business activity and with multiple newsworthy events happening at the same time. The lowest point (26.36%) marks the first week of the year, when Russians are on holiday, with few things happening and with the bulk of viewers drawn to the entertainment segment. The second lowest point (30.56%) is usually recorded between May 2 and May 8, i.e. during the so-called May holidays. After the start of the so-called «special operation», viewers coalesced around the three main TV channels that actively broadcasted news and offered commentary on the course of the hostilities. The week between February 28 and March 6, the first full week after the outbreak of the war, proved to be the most successful one in terms of the sheer proportion of TV audiences garnered by these three channels. That week, Channel One, Rossia-1 and NTV together managed to attract 35.45% of the total TV viewership. After this peak the size of their audience share fluctuated until one week in mid September (September 12−18) when it rose to 31.59%. The following week it grew again by 2% It is worth recalling that the Kremlin announced «partial mobilization» on September 21.

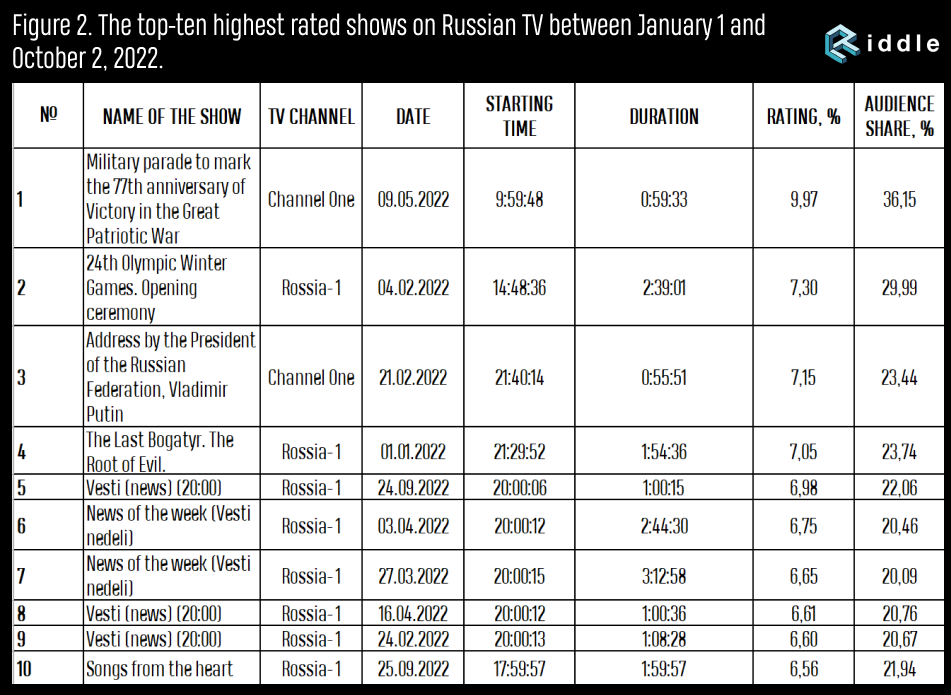

The May 9 broadcasting of the military parade on Channel One, watched by 9.97% of all of Russia’s TV viewers, tops the list of the most watched programs of 2022. Significantly less popular with the viewers was the opening of the XXIV Winter Olympics broadcasted by Rossia-1. The third most popular program was the February 21 Russian President’s address to the nation that aired on Channel One. In addition, five evening newscasts of Vesti and two entertainment programs made it into the top-ten list: the evening film screening The Last Bogatyr. The Root of Evil shown on January 1, and the music program Songs from the Heart that aired on September 25.

Thus, through 2022, television audiences remained loyal to the three leading TV broadcasters and maintained trust in them. At the same time, news and socio-political content came to the fore. Although the results of the research indicate a certain weariness of information broadcasting, a weariness that peaked in mid-September, it dissipated with the onset of mobilization.

Social media reconfiguration

Perhaps the most interesting story for anyone studying Russian media consumers this year is still the redistribution of audiences within the social media segment. On March 21, 2022, Russian authorities declared Meta, the owner of Facebook, Instagram and WhatsApp, an extremist organization, effectively banning its activities in the country. Earlier that year the Federal Service for Supervision of Communications, Information Technology and Mass Media (Roskomnadzor) blocked the first two of the three listed social media platforms, so Russian users can now only access them through VPN services.

Due to the court ruling, Meta discontinued its business in Russia. Accordingly, Facebook and Instagram ceased to operate as advertising platforms. This decision dealt a heavy blow to Instagram influencers, dramatically reducing their opportunities to monetize their online activities. Until recently, the Russian market for influencer marketing was developing quite dynamically. According to IAB Russia, in 2018, it was worth RUB 5bn but had grown to 18bn by 2021, with Instagram, along with YouTube and TikTok, among the top three advertising channels. The departure of one of the key players on the market offers a window of opportunity to several Russian platforms, most notably, VKontakte and Yandex.Zen.

What impact have the changes in the social media market had on audience behavior? Findings published by Mediscope, the Russian Association for Electronic Communications (RAEC), Brand Analytics and several other research groups enable us to reconstruct the dynamics.

First of all, most of the Russian users normally have accounts on several platforms. According to the RAEC/OMI Russia online survey of Russian social media users conducted in March 2022 (n=1640), one person would have 3.6 accounts on average on some of the ten social platforms listed in the questionnaire. Granted, the scope and nature of individual activity on these platforms can vary. Moreover, by activity we mean at least three different types of actions that should be considered: consumption, discussion and content sharing/posting.

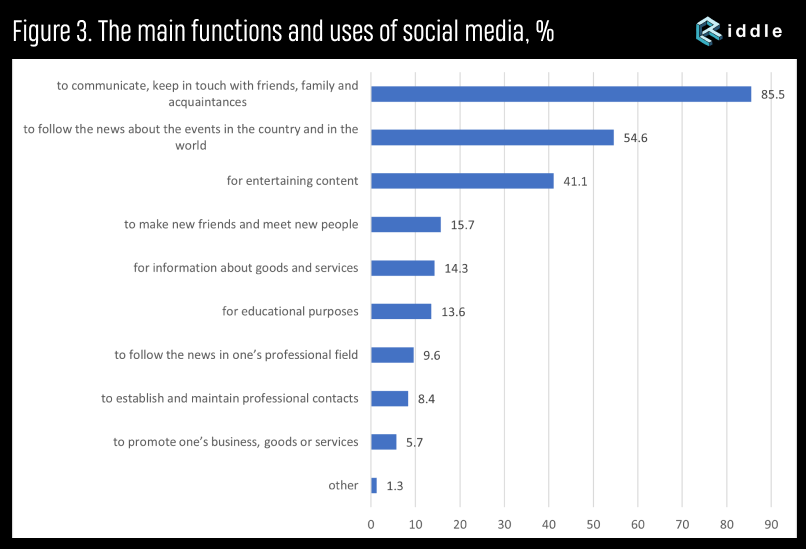

Research indicates that despite a certain upsurge in account deletion on foreign social media platforms (primarily those belonging to Meta) in March, only a minority of users chose to completely abstain from using these networks. One possible explanation — a particular value allocated to «communication, keeping in touch with friends, relatives and acquaintances», which 85.5% of users believe to be the main function of various social media. By comparison, the second most popular function -«following news about the events in the country and in the world» — was chosen by 54.6% of respondents. The majority of users decided not to burn their bridges and keep their personal «journals». At the same time, 38% of those polled by the Public Opinion Foundation said they did not consider the use of social networks blocked in Russia to be anything reprehensible, against 18% of the respondents who noted that such behavior is unacceptable.

The Chinese network TikTok has been a curious case in point. It has been neither blocked nor banned by the Russian authorities. However, in early March, the network’s owners decided to ban livestreaming and uploading of new content in Russia after the Kremlin passed the law criminalizing the spreading of what it deems to be fake news about its invasion of Ukraine. Access to non-Russian content was also blocked. There have been occasional reports that the network would unblock its services for Russian users, but TikTok’s management has denied them.

If we consider audience coverage as an indicator (the number of people visiting a site at least once a month or once a day) as estimated by Mediascope, the following picture emerges. Between January and August 2022, YouTube (Russia’s leading social media site in terms of monthly audience reach), VKontakte and WhatsApp demonstrated a slight upward trend, while the number of TikTok users declined slightly. Instagram was the obvious loser as since March it has no longer been featured in Mediascope’s Top 10 Web-Index report. (It should be noted that Brand Analytics recorded a drop of 48% in the number of active Russian-speaking Instagram users between February 24 and April 6). However, since April, Telegram, apparently the main beneficiary of the shift in audiences that left Instagram and Facebook, has confidently made it into the top-ten list. Users perceive Telegram as a safer platform, but it lags far behind WhatsApp in terms of popularity: the daily reach of Telegram’s Russian audience in August (age 12+) was 34.4%, compared to 59.4% for WhatsApp.

The changes tn 2022’s media sphere, were, on the one hand, a logical development of previously recorded trends; on the other, they failed to yield a radical transformation. Public and political television broadcasting have retained its loyal audience and consolidated it around a state-manufactured agenda. By adding pressure on alternative media, the state has been able to shape a non-controversial and favorable information context that shapes the key issues presented to the public. Despite the demise of the social media market, the departure of foreign players does not seem final and irreversible. The latter may, under certain conditions, regain their lost positions, as conservative audience behavior does not preclude the possibility of future changes in the media sphere.