While a great deal of media analysis since Russia’s full scale Ukraine invasion rightly focuses on the role and content of social networking channels related to the war, Russian broadcast television still plays a central role in framing Russia’s war for domestic consumption. Indeed, Russia’s media environment is somewhat unusual in its relation to social media: whereas social media increasingly drives the content and agendas of legacy media worldwide, Russia’s pro-government social networking accounts and channels tend to follow the lead of state media.

Method & Approach

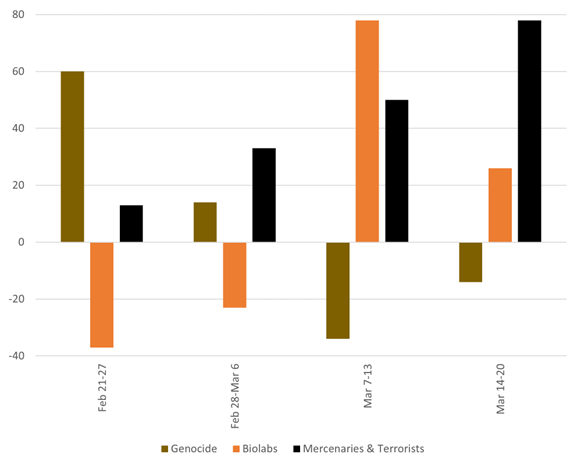

The Russian Media Observation and Reporting (RuMOR) project tracks Russia’s war reporting on broadcast television. The RuMOR team analyzes broadcast transcripts from national television channels provided by Integrum to measure the prevalence of keywords associated with the ways that Russia explains the war to domestic audiences. Though the transcripts do not include political talk shows like Vremia Pokazhet («Time Will Tell»), daily news broadcasts on state-run and state-controlled television reach a wider range of casual viewers that do not seek out pro-regime propaganda. Moreover, news broadcasts permit observations of changes in narrative content over time as messages are fine tuned for viewing audiences in Russia. For example, mentions of «genocide» sharply increased with the start of the war, along with the claim that Russia was intervening to prevent genocide in the Donbas region. Two weeks later, mentions of genocide virtually disappeared from the airwaves while mentions of «biolabs» spiked along with tales of US-sponsored biolaboratories in Ukraine. In turn, the biolab narrative was soon supplanted by stories of mercenaries and terrorists.

Figure 1: Shifting Narratives on Russian TV, February-March 2022

To what extent is national television likely to affect the ways that Russians view the war? In domestic news consumption, it has long been the case that a majority of Russians get their news from television, even as younger generations increasingly turn to social media platforms like Telegram. While survey-based research in Russia is unreliable and even harmful under conditions of wartime censorship and repression, alternative attempts to gauge public opinion like the RussiaWatcher project suggest that this trend has continued since Russia launched its invasion of Ukraine. As topic mentions on national television will be noticed by casual viewers in Russia, RuMOR calibrates topic mentions relative to the weather as a threshold for everyday relevance: if a topic is mentioned more often than the weather, it is more likely to be noticed during viewers’ day-to-day routines.

Normalizing the War

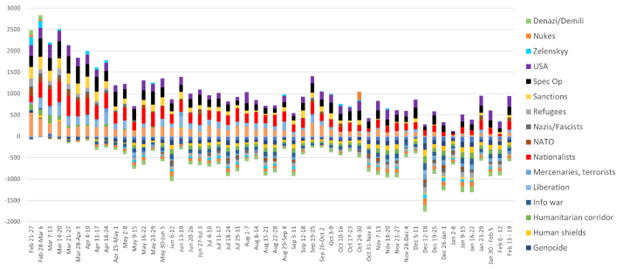

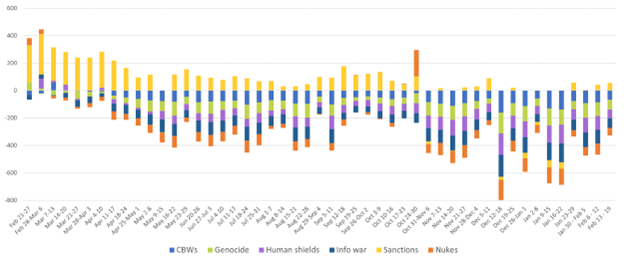

At first glance, there is a bewildering array of topic mentions over the first year of Russia’s war. This «spaghetti chart» shows how quickly Russian television shifts focus.

Figure 2: Total Mentions on Russian TV, February 2022-February 2023

While some of this coverage is driven by real-time events, re-calibrating relative to the weather yields a surprising finding: the war steadily faded from Russian televisions.

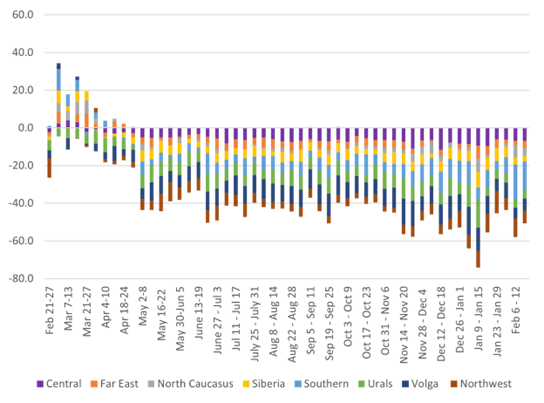

Figure 3: The War vs the Weather on Russian TV

In this way, Russian television news normalizes the war for Russian viewers, inserting it into people’s daily routines rather than seeking to change them. Normalizing the war may seem a peculiar strategy, as most casual observers would expect governments to mobilize public support in times of war. However, as is common among autocracies, Russia’s rulers prefer to keep the public de-mobilized, apolitical, and loyal to the state. A core goal of domestic propaganda, then, is to persuade Russians that the war is not a dramatic rupture; rather, it is the logical extension of long-established claims that Ukraine as a state is not legitimate, Ukrainians as a people are not really Ukrainian, and the West is Russophobic to irrational extremes.

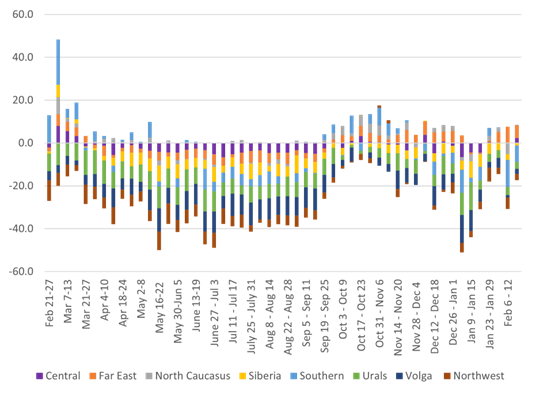

The situation is even more striking when looking at regional television channels, where the «special military operation» is (at most) background noise. Of the few topics covered on regional television, mentions of sanctions illustrate the way that the war is normalized: while we observed some sustained discussion of sanctions early in the war, these framed Western sanctions as a continuation of the sanctions regime imposed since 2014.

Figure 4: Mentions of Sanctions on Regional TV

Similarly, the response to new sanctions mirrored those of past years in trumpeting the benefits of import substitution, benefiting domestic economic competition, and improving national security by reliance on domestic goods and technology. In other words, sanctions were framed as threatening but nothing new and ultimately toothless.

Enemies, Logic, and Legitimation

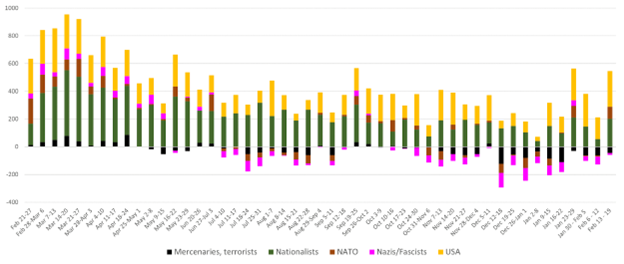

Breaking down coverage of the war on Russian television into narrative elements of actors and motives, there is a disproportionate emphasis on mentioning Russia’s enemies: Ukrainian nationalists, the United States, NATO, Nazis or fascists, mercenaries and terrorists.

Figure 5: The War vs the Weather on Russian TV: Enemies

Of these, the primary focus is on Ukrainian nationalists and the USA. Despite Putin’s declared war aim of «denazification» of Ukraine, Nazis are rarely mentioned in war coverage. If «nationalists» was used at the start of the war to distinguish between alleged radicals and Ukraine’s regular armed forces, they soon came to be used interchangeably.

By contrast, depictions of Russia’s enemies often are shorn of any logic or rationale. Mentions of enemy machinations similarly declined quickly following the start of the war, with only sanctions regularly rising above the background noise.

Figure 6: The War vs the Weather on Russian TV: Plots Against Russia

In other words, domestic Russian television inundates viewers with mentions of Russia’s enemies but often without any rationale other than allegedly hating Russia and Russians: what they are doing and why is less important than reminding viewers that they exist and, by implication, that Russia’s state is the only thing standing in their way.

At the same time, Russia’s own motivations in the «special military operation» receded from view throughout the first year of the war.

Figure 7: The War vs the Weather on Russian TV: Legitimation

In fact, the goal of de-nazification declared in Putin’s televised speech on February 24, 2022, faded from view after just two weeks. Liberating Ukrainian territory was a prominent legitimating goal of the SMO through the first seven months but, by the end of the first year, television coverage largely just flagged the ongoing SMO. In this fashion, declining concern to provide legitimacy to the war on national television reflects its normalization as a routine and expected fact of daily life in Russia. However, it is notable that the absence of the war on regional television was interrupted during the time of partial mobilization: mentions of the SMO rose particularly in the Southern and Far Eastern federal districts, belying the need to bolster the war’s legitimacy in the regions that likely provided larger shares of Russia’s casualties.

Figure 8: Mentions of Special Military Operation on Regional TV

The Shifting Role of NATO on Russian Television

It is somewhat surprising that NATO is not discussed more frequently on Russian television, especially relative to other enemies in Russia’s war. In fact, NATO provides a useful illustration of the narrative drift and even contradictions in Russia’s domestic propaganda. Prior to the war, there was a high level of references to NATO, which was portrayed as an instrument of US foreign policy and an embodiment of anti-Russian ideology. Moscow’s demands in negotiations with the United States in December 2021, such as rolling back NATO expansion and the non-deployment of weapons near Russian borders, were frequently emphasized in presenting NATO as an aggressive alliance directed by the US. Following Putin’s speech launching the current war on February 24, 2022, Russian television highlighted his comments about Ukraine as a hostile «anti-Russia» entity near its borders, under external control and heavily armed by NATO.

As time progressed, the number of references to NATO declined, with occasional spikes during meetings of member countries, conferences, and negotiations. One topic that received considerable coverage was the potential entry of Sweden and Finland into NATO. Russian media adopted a relatively neutral tone, emphasizing that the membership of Finland and Sweden in NATO differed significantly from that of Ukraine as they did not have territorial issues or disputes that would directly bother Moscow. This shift in tone was likely driven by the need to minimize the perception of NATO’s enlargement as an unintended consequence of Russia’s war, but it effectively redirected the narrative away from the ideological anti-Russian component of the Alliance. Instead, Russian media began to highlight Western military movements, deployments, and unfulfilled promises of NATO membership to Ukraine, particularly concerning military supplies from member states. Today, references to NATO in Russian media no longer solely portray it as the main cause of tension or the primary enemy of Moscow. Rather, NATO has become a flexible argument employed by the government to serve various purposes, conveniently adapting to different explanations and legitimization strategies.

The Great Patriotic War: Blurring the Narrative

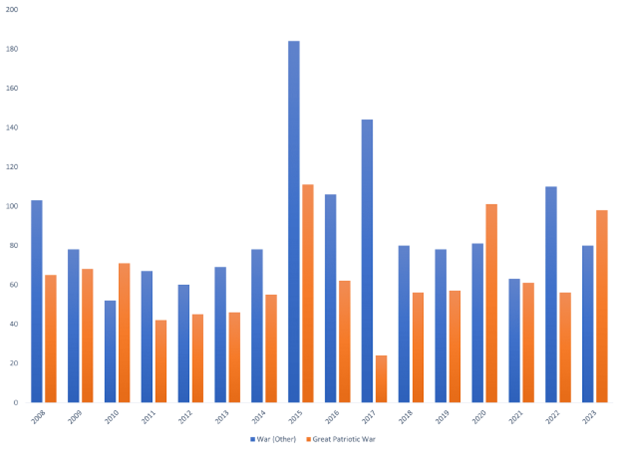

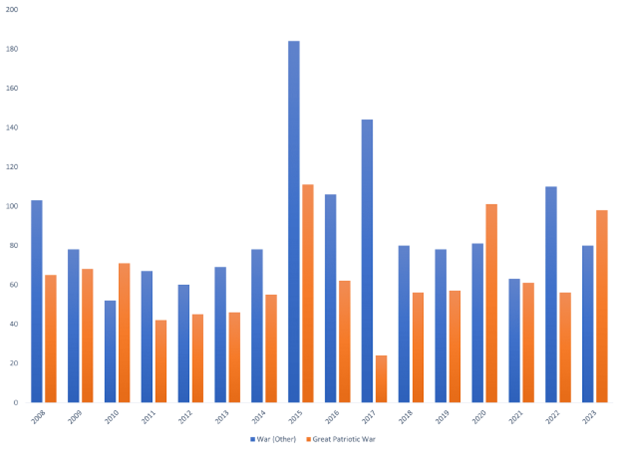

As with Russia’s occupation and annexation of Crimea in 2014, domestic propaganda wraps the full scale invasion of Ukraine in 2022−2023 in the symbolism of the Great Patriotic War (Second World War). The Great Patriotic War remains a consistent topic of discussion on Russian television, and the viewing calendar is littered with frequent observations of war history. In fact, discussions related to the Great Patriotic War have become more prominent since the beginning of this year while unrelated mentions of «war» have declined since last year.

The role of the Great Patriotic War on Russian television is not just important in a symbolic sense. Over the last decade, discussions of military topics over the years have been nearly matched by dialogue surrounding the Great Patriotic War.

Figure 9: War Talk on Russian TV, January-March (Average Weekly Mentions)

In other words, the growth of coverage of the Great Patriotic War coincided with (and partly concealed) a broader increase in «war talk» on Russian television. To achieve the merging of discussions between the war in Ukraine and the Great Patriotic War, the media and the government portray patriotic figures and appropriate cultural memory, aiming to unite respect for the past with loyalty to current policies. The objective is to find a common national idea that can bridge the gaps within a diverse country encompassing various ethnic, religious, and ideological backgrounds. These endeavors underscore the widespread acceptance among Russians of a historical narrative that justifies the ongoing conflict.

However, the convergence of discussions regarding the war in Ukraine and the Great Patriotic War potentially has unintended consequences. Not only does this mnemonic strategy obscure the understanding of warfare in Russia but also undermines its gravity. As we have already seen, above, core mnemonic associations tied to the Great Patriotic War such as patriotism, nazis/fascists, and denazification/demilitarization, are used sparingly. The strategy of normalizing and downplaying the war thus undercuts the desired emotional weight of association with the Great Patriotic War. Added to this, it becomes challenging to draw convincing parallels between the war on Ukraine and the initial associations presented to justify Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. Consequently, the media shaped the narrative of the Great Patriotic War around the unification of the Russian people, the perpetuation of a collective narrative, and the legitimation of the intervention, while the actual war on Ukraine assumed a secondary role.

Conclusion

The patterns of normalizing and historicizing the invasion of Ukraine for Russian television audiences may help to understand the Russian public’s response to the war, though one should not treat viewers in Russia as a captive audience as there are many alternative sources of information that are accessible even from within Russia. Nevertheless, the RuMOR data demonstrates what kinds of narrative associations that Russians passively consume in everyday life while the news blares in the background at home, at the salon, in a taxi, or while shopping. These narratives become the assumed givens of everyday life, while publicly challenging them invites prosecution under the draconian censorship laws adopted shortly after the start of the war. Awareness of the state’s willingness to repress along with pervasively available narratives about Russia’s war goes a long way towards explaining the absence of open dissent. In the absence of actual information about enemies’ rationales, enemy images substitute for logic while associations with the Great Patriotic War provide legitimation and attach a social imperative for unifying behind the state.

The tendency of normalizing and downplaying the war in everyday life also makes particular events stand out against this pattern. A little over a month after celebrating the annexation of four Ukrainian regions, Russia was forced to retreat from the capital city of Kherson in early November 2022. While coverage of Kherson sharply increased, there was just one passing mention on state television of the retreat (which was characterized as a repositioning of Russian forces to better protect local populations). More recently, the attack on Shebekino in Belgorod similarly saw a spike in mentions, but just one mention of the attack occurring on Russian soil followed by a quick series of emphatic denials (and no mention of the role of Russian partisans). In both cases, the notion of Russian or Russian-occupied territories at risk was clearly unexpected and risked disrupting the normalizing tenor of war reporting. The surge in televised discussion in each case likely was driven less by the events at hand than the perceived need to counter the surge of information on social media. Narratives drifted and collided as state television worked out its messaging.

Figure 10: Explaining the Attack on Belgorod on Russian TV (May 29-June 4, 2023)

Unlike the retreat from Kherson or the attacks on Belgorod, the destruction of the Kakhovka Dam was reported from the start by state television as a terrorist attack by Ukraine and there was little narrative drift. The media immediately framed the attack in terms of the enemy’s logic and long-term planning—a rarity, as we’ve already seen—and characterized the attack as a catastrophe while emphasizing the lack of threat to Crimea’s water supply or the Zaporizhzhia nuclear power plant. By the second day of the crisis, it already shifted focus to Ukraine’s allegedly failing counter-offensive and Tucker Carlson’s claims on his new Twitter show.

Figure 11: Explaining the Kakhovka Dam on Russian TV (June 6−8, 2023)

When viewed in context, then, such ruptures in the normalizing pattern of Russian television’s war reporting can provide powerful insight about state perceptions of threatening developments (as with the retreat from Kherson or the fighting in Shebekino). Likewise, they can also reveal when state television is far too prepared for developments for which Russia hopes to evade responsibility, such as the destruction of the Kakhovka Dam.

By far the most significant rupture in the usual cadence of propaganda on Russian television was the armed revolt led by Evgenii Prigozhin that began late at night on June 23. The extent of panic caused by the mutiny is reflected in the sheer variety of narratives broadcast on state television over the course of just one day, especially when compared to previous crises. As with the attack on Belgorod, the reporting on the mutiny contained strategic silences: it did not mention that a second column of Wagner forces was headed towards Moscow or that the Wagnerites shot down several military aircraft. In this instance, however, state television raced to keep up with Telegram, where Prigozhin launched his mutiny, and where various channels reported on the actual progress of the Wagner column headed towards Moscow.

As a result, announcers made increasingly desperate pleas for viewers to ignore «non-official information sources.»

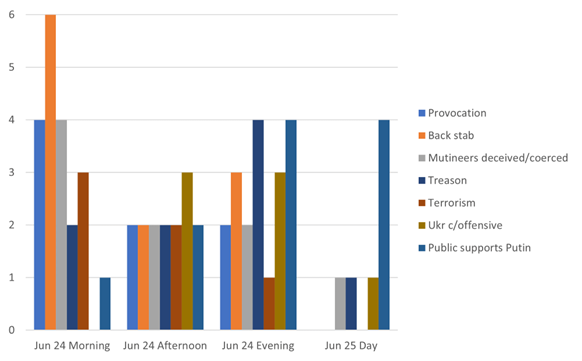

Figure 12: Explaining the Prigozhin mutiny on Russian state TV (June 24−25, 2023)

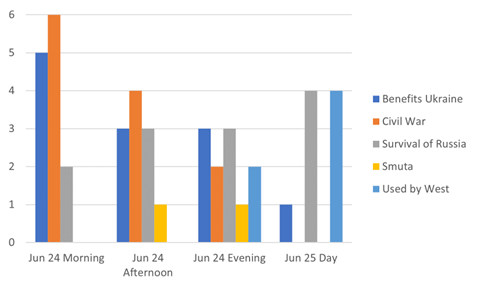

The resolution of the mutiny coincided with a return to normalcy in reporting. First, the underlying claim of overwhelming public support for Putin escalated throughout June 24−25. This coincided with television’s portrayal of the nature of the threat posed by the mutiny. Out of the gates, the mutiny was described as risking civil war—a depiction that was bolstered by Putin’s televised address on the morning of June 24 when we invoked the memory of 1917 and the Russian Civil War. By the time that the mutiny was resolved, however, reporting shifted back towards the West as an existential threat to Russia’s survival.

Figure 13: Threats posed by the Prigozhin mutiny on Russian TV (June 24−25, 2023)

In this fashion, the Prigozhin mutiny provides perhaps the most vivid example of how Russian television normalizes the war through the use of enemy images shorn of logic, flexible usage of the West to legitimate the Kremlin response, reference to historical analogy to conjure an emotional connection for viewers, and Putin as the inevitable, unmovable point at the center.