Alexander Kharichev, the head of the Kremlin’s social monitoring unit and a close ally of Sergei Kiriyenko—the architect of the president’s political machine—has clearly caught the bug for penning ideological manifestos. His latest opus, titled with ponderous gravitas as «Who Are We?», has just landed in the pages of The State, a journal recently rebooted by the Russian Presidential Academy of National Economy and Public Administration (RANHiGS), the Kremlin’s premier forge for loyal bureaucrats. (Riddle Russia has a copy of the text.) In it, Kharichev largely recycles the core tenets from his earlier Putinist playbook, «Russian Civilization,» published back in April. Drawing on what he presents as quasi-scientific musings, he insists that Russians are wired for collectivism over individualism, faith over cold rationality. Citizens here, he claims, prize moral norms above the letter of the law and cling fiercely to traditional family values. The litany of threats facing Russia—or more precisely, the Kremlin—remains familiar: societal fractures, Western plots to erode sovereignty, and a nagging demographic crunch.

Yet in this fresh dispatch, Kharichev lays it on thicker. Where he once fretted over mere «divisions» in society, he now pairs it with «civil war.» The birth-rate slump? Straight-up «depopulation.» In his prior piece, he suggested Russians «more readily lay down their lives for higher causes.» This time, he amps it up: «It turns out that for us, life is worth far less than it is for a Western individual. We believe there are things more important than mere existence.» That’s no longer a meditation on noble sacrifice—it’s a blunt declaration that, for the Russian soul, one’s own life supposedly holds little intrinsic value.

Commentators have zeroed in on the official’s stark invocation of «civil war.» The full quote runs: «Much has been written about rifts and contradictions. In essence, society faces one grave challenge, simply named—civil war: the disunity of people, the fracturing of the country, the loss of the will to fight for its preservation and progress. We’ve endured this in our history at least twice: in the 17th and 20th centuries. And who says it can’t happen again? It could be triggered by any number of factors—ethnic or religious clashes, generational or class divides. But it’s a risk, or rather a perpetual challenge and threat, embedded in every social system.» In Kharichev’s framing, «split» or «civil war» isn’t some bespoke Russian curse—it’s the baked-in peril for any nation, any society.

Still, dropping «civil war» alongside the Time of Troubles in the 17th century and the Great October Revolution isn’t casual. It’s a nod to the same lexicon Vladimir Putin deploys, the ultimate audience for Kharichev’s screeds. It’s Putin whom Kiriyenko’s lieutenant is really wooing here, dialing up the alarmism to drive home a few key pitches. First: Doubting the wisdom of unpopular wartime fiscal squeezes is futile—Russians, after all, don’t cling to life itself, let alone their wallets. So they’ll swallow tax hikes, fresh waves of mobilization, whatever’s ordered. The Kremlin’s political bloc need only trot out the old line—”The Motherland calls”—and explanations become optional. Second, against this grim canvas, Kharichev is pushing a stalled bill on patriotic education (flagged in the media last fall, but mired in red tape). His political block would run the show, pocketing yet another lever of control.

Kharichev even spells out a bold, chilling endgame: «upbringing for the human of the future,» one «suited to the task of preserving and advancing our civilizational system.» The Kremlin apparatchik lays bare a utilitarian view of the citizen as a cog «fulfilling a mission» (near-military jargon) for the state’s survival—existing for the state, not the other way around. To get there, instill «collectivism» and «service”—staples in Kharichev’s oeuvre. And who’ll oversee this grand re-education? The Kremlin’s political bloc, naturally. It’s for these expanded powers that Kharichev cranks the rhetoric to eleven, shifting the discourse into the stark, existential tones Putin grasps intuitively.

The Tver Gubernatorial Quagmire

Vladimir Putin tapped former Federal Antimonopoly Service chief Vitaly Korolev to helm Tver Oblast—and he jumped at it. The governor’s seat had sat vacant for over a month after Igor Rudenya, the previous incumbent, was shunted to presidential envoy in the Northwestern Federal District (NWFD). That move caught the power vertical off guard, unfolding with unusual haste. Ex-envoy Alexander Gutsan had just been named prosecutor general, while Dmitry Kozak—Putin’s pick for the NWFD post—opted to quit the Kremlin altogether. The NWFD slot sparked a scramble (not least from Lyubov Sovereva, the deputy envoy for policy and a Kovalchuk brothers’ ally), but Tver’s governorship held zero allure.

The region chugged along sans Putin-anointed boss for weeks, spawning wisecracks in Russia’s political Telegram channels: If Tver’s thriving fine without a governor, why bother with the job at all? These jabs missed the mark—interim leadership and the bureaucracy kept things ticking. Even if you scrapped the governorship outright (though regional headships are enshrined in the Constitution), Moscow would still install a handler by another name: state manager, or something more evocative like «viceroy.»

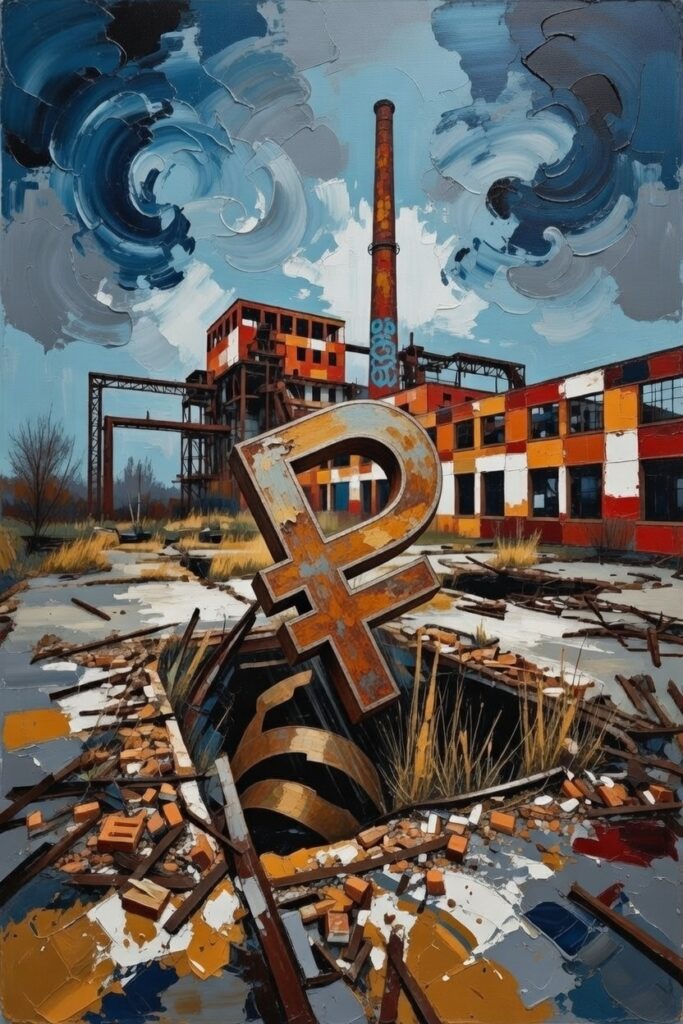

The real story here? The delay stemmed from the Kremlin’s struggle to find anyone willing to take the gig. It’s not unprecedented. Take Karelia: Ex-Vologda premier Anton Kolytsov, fresh off a stint in annexed Zaporizhzhia and now running occupied Mariupol, passed. In stepped holdover Artur Parfenchikov, a gubernatorial veteran. The same for Bryansk’s Alexander Bogomaz and Kostroma’s Sergei Sytnikov—outliers in a pool dominated by Kiriyenko’s academy grads. Moscow likely couldn’t (or wouldn’t) swap them out. More accurately, it failed to lure any solid, high-caliber bureaucrat to these backwaters. Karelia, Bryansk, and Kostroma rank among Russia’s depressed territories. Amid fiscal squeezes, ambitious climbers shun them: No glory to be had, just blame for the war’s fallout. These hiring headaches are birthing a succession quirk: Governors promoted upward now hand off to their deputies, as seen in Novgorod.

The Kremlin once airbrushed such talent crunches, never admitting a whiff of trouble. With Tver, though, it went public. An Administration-loyal outlet, Kommersant, revealed that deputy natural resources minister Denis Butsaev and presidential aide Viktor Evtukhov (overseeing defense-industry policy) both said no. RBC piled on with another decliner: Vasily Toloko, ex-Tver city manager and now federal economic development honcho.

Tver’s no paradise—it’s got that depressed-region vibe—but it boasts upsides absent in Bryansk, Kostroma, or Karelia. Zavodovo hosts a Kremlin retreat, ringed by oligarch dachas. A handful of big factories limp along (like most Russian firms these days) but could rebound. Still, big-league officials balked, even as Butsaev once eyed a pre-war governorship in Belgorod.

Airing the Tver fiasco signals a deeper rot in the Kremlin’s governor-picking machine. It’s a not-so-subtle prod to the top brass—and a warning shot to the holdouts—that patience is thinning. Fat chance it’ll stick: Federal functionaries are digging in at the White House, loath to torch their trajectories in the sticks.

Expect the gubernatorial ranks to thin out. Regions will draw not from deputy ministers or key apparatchiks, but lower-tier drones. Or, potentially, Kremlin black sheep exiled as punishment. The playbook’s been tested: Just look at Andrei Turchak—ex-head of United Russia’s general council—parachuted into Altai Republic.