Putin’s rejection of Trump and Zelenskyy’s initial ceasefire offer—couched in language that downplays the persistent maximalism of Russia’s negotiating stance—sets the stage for a turbulent six months ahead. Slowing offensive operations to reconstitute units, while sustaining attacks on Ukrainian civilians to shift the political climate against Zelenskyy, buys time for the economy to adapt to what increasingly looks like a far tougher external environment, regardless of sanctions pressure or ruble appreciation.

Risks tied to Iranian supplies—stemming from U.S. sanctions pressure on China’s imports of Iranian crude for so-called teapot refiners (independent refineries not controlled by state or state-adjacent oil firms)—have staved off a steeper price sell-off. Still, Brent crude is trading at $ 72 a barrel, and forward-looking indicators for oil prices aren’t encouraging. China cut imports from Russia by 12.6% year-on-year in January-February, part of a broader strategy suggesting Chinese importers may be holding off for lower prices before ramping up purchases. Alexander Novak led talks with OPEC+, pledging Russia to join compensatory oil production cuts to offset overproduction within the bloc—a reduction exceeding 100,000 barrels per day by June. It’s the latest sign that balancing oil markets is growing trickier. Without geopolitical disruptions, prices won’t hold much above $ 70 as new projects adding significant capacity come online this year. That spells discomfort as summer nears.

Turkey has reportedly struck a deal with U.S. officials to pay for gas imports via Gazprombank through May, sidestepping current sanctions and paving the way for future talks. Meanwhile, Turkey has scaled back direct crude oil purchases from Russia, turning instead to Brazil for more supply. Nothing will halt Russian exports from reaching markets, nor will the price cap bite deeply until tougher measures target the shadow fleet. Yet this horse-trading over trade flows underscores the muddled standoff between Moscow and Washington. The Trump administration lacks direct leverage to force Putin to drop demands without tighter allied coordination—a prospect undermined by the unsubtle, erratic, and shortsighted moves of Vice President Vance, like-minded U.S. officials, and Trump’s bizarre North American trade war. Russia, likewise, has no meaningful economic leverage to punish the West.

For Russia’s bargaining position in the coming months, internal struggles over influence and state resources in a visibly slowing economy matter most. Igor Sechin claims Rosneft contributed 6.1 trillion rubles to the consolidated budget last year—a figure that only makes sense if it includes a broad swath of regional spending offloaded onto state firms, possibly financed through domestic debt issuance. It’s another chance for Sechin to flaunt Rosneft’s central role in generating tax revenue and meeting regime spending needs. He announced the sum at a Russian Union of Industrialists and Entrepreneurs meeting. Notably, Putin made it clear that businesses shouldn’t expect sanctions or other pressures to ease anytime soon. This wasn’t the tone of someone nearing a peace deal with the U.S.; instead, he promised the state would do what it could to help.

Productivity remains the biggest hurdle for policymakers papering over the mounting cracks in living standards and war demands. Now, claims abound that «Industry 5.0″—melding human labor with AI, robotics, and other advances across 30 clusters by 2030—could lift GDP growth to 4% annually. Whatever aid businesses receive, officials are effectively recycling the hollow promises of miraculous technological leaps from the Brezhnev and early Gorbachev eras. Stranger still is how detached this faith in a breakthrough—echoing Mishustin’s COVID-era «acceleration» of technical processes, a nod to Gorbachev—is from the war economy’s realities. Growth demands far more mundane, fundamental policy shifts.

Big businesses have warned Putin and others in recent weeks that high interest rates risk sparking a non-payments crisis unseen since the late 1990s. With the key rate at 21%, more state corporations and resource giants are delaying payments for months, keeping funds in interest-bearing bank deposits before settling contracts and pocketing the profits. This issue has simmered since last fall when Alexander Shokhin and business leaders flagged the growing financial strain from high rates, compounded by MinFin’s cap on advance payments at 30−50% of contract value, with the rest due upon delivery. With inflation outpacing official figures, companies face rapidly rising costs against static contract values.

Withheld payments are just one facet of interlocking challenges tied to war-spending-driven inflation. Debts for utility payments pile up due to more frequent and steeper tariff hikes. Strained transport capacity in the Far East drives up consumer prices, and so on. Putin now signals an unavoidable economic slowdown requiring careful handling. Maxim Reshetnikov and the Ministry of Economic Development are telling the public that macroeconomic stability—not development—is the top priority, war notwithstanding. Yet even their supposedly «ambitious» targets for fixed asset investment—a gauge of spending on expanding economic capacity—aim only for a 60% increase over 2020 levels by 2030. They’re benchmarking against the COVID shock and counting massive military production investments toward the goal.

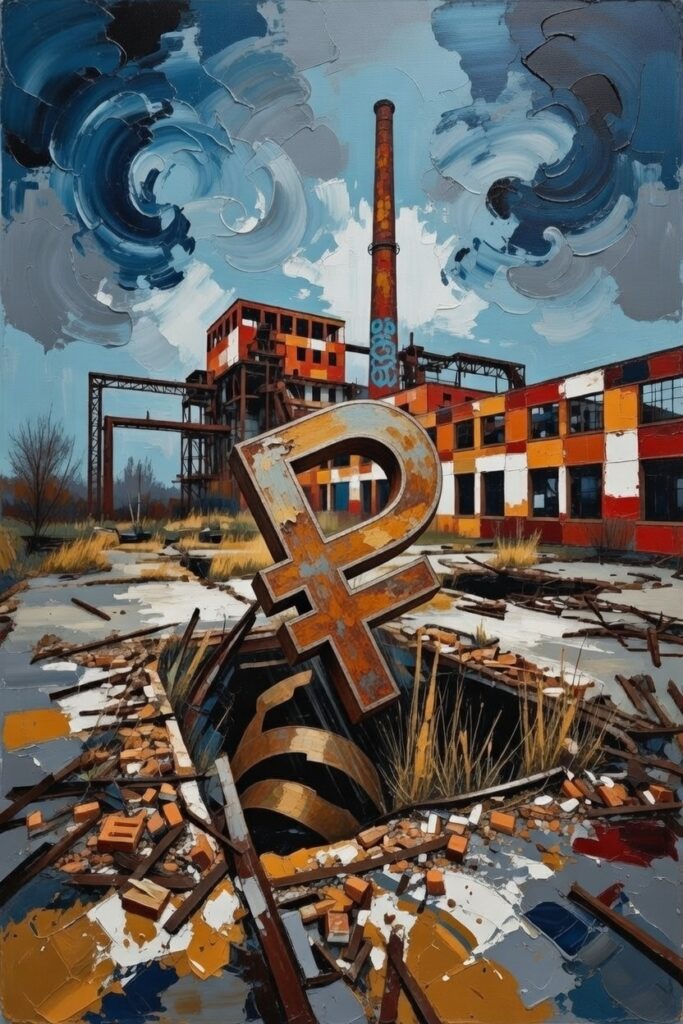

With the National Welfare Fund dwindling and deficits needing to stay near 2% of GDP to avoid worsening inflation, Siluanov and MinFin are reviving talk of «big» privatization. Putin tasked them with boosting the market capitalization of Russia’s listed firms to two-thirds of GDP—a level last seen above 60% in 2010. Privatizing state assets again might offer saving households a new investment outlet, but debt servicing costs loom large. Annual budget spending on debt service hit 2.33 trillion rubles in 2024, up 35% from 2023. At nearly 6% of the federal budget and climbing due to high rates, it’s a growing burden. Regions no longer show profit tax revenue growth. While none of this signals a political crisis, headwinds outnumber tailwinds. Amid Europe’s largest land war since WWII, steel producers grapple with delayed payments and slumping demand.

The plan, it seems, is to stay the course. Typically, we ask if Russia can sustain its war effort. But we should flip the question: Why isn’t the regime fully mobilizing the economy for war, as Ukraine has? The answer is unsatisfying but critical. If war spending is the «motor» for growth, too many stress points and failure risks now riddle that motor to push it harder without breaking it. There’s no preparation for peace or a post-war economy. That suggests talks in Riyadh will yield little for now and that losing at the front is easier to manage than winning. Defeat can be spun; victory demands an economic overhaul the regime has never shown it can handle without a unifying cause or external jolt.