Discussions about the possible transformation of Russia’s modern economy into a Soviet-style economy are gaining momentum. This debate began around 2015, when the term «Gosplan 2.0» was coined by political consultant Evgeny Minchenko and entered common usage. With the start of the full-scale war in Ukraine and the sharp intensification of nationalization processes, this scenario has begun to be viewed as entirely realistic. The most recent material on this topic is an article by Vladislav Inozemtsev published on Riddle Russia.

To assess the likelihood of such a transition in modern Russia, it is necessary to highlight the key principles of the Soviet economy (Russia’s movement toward this model would mean the consistent implementation of all these elements into the current economic system):

- Rigid planned management. The state set mandatory production plans for enterprises;

- Centralized supply. All resources were provided to enterprises by the state;

- State regulation of prices. Prices for goods and services were set centrally;

- Monopoly on foreign trade. The state fully controlled exports and imports.

The mechanism worked as follows: the state determined the production plan, provided the enterprise with the necessary finances and material resources, and then specified exactly who the products should be delivered to.

In this article, we will determine whether we are indeed observing a transition to a command economy. Is it possible in a gradual form, or is a sudden collapse necessary, similar to what occurred after 1917? If a gradual transition is possible, at what point will it become irreversible?

Based on the available signs, such a transition is indeed occurring, but it affects not all sectors of the economy and has not yet yielded significant results.

Pragmatism of the Elites and Pseudo-Statization

Let’s start with nationalization. The nationalization process in modern Russia differs from the Soviet experience. In the USSR, nationalization was carried out for ideological reasons, not economic necessity. However, when ideology failed to fill store shelves, the authorities were forced to retreat to the New Economic Policy (NEP). The modern Russian elite acts pragmatically, without ideological underpinnings. Nationalization under current conditions serves as a tool for fighting for power and financial resources. The existing level of inequality, in which the wealth of oligarchs close to power has significantly increased during the war, fully suits the elite. At the same time, inequality in Russian society is increasing.

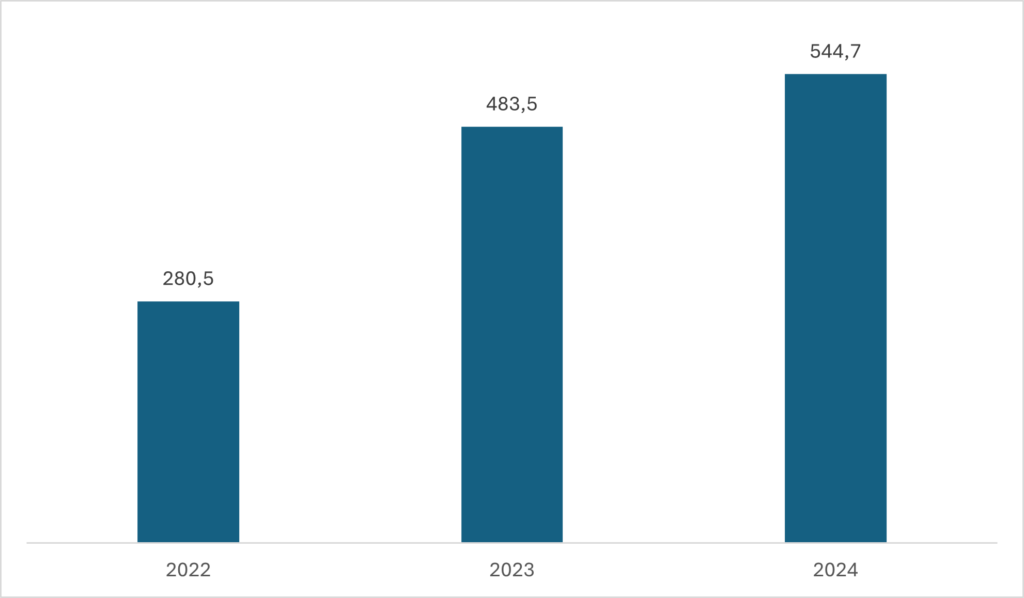

At present, a noticeable process of transferring businesses under state «patronage» is observed, as evidenced by data on the assets of nationalized enterprises (Fig. 1). However, this does not mean that such enterprises automatically become part of the command-administrative system. The role of the new owners is not reduced to the function of state managers—rather, they can be characterized as temporary custodians whose position lasts only as long as they do not make serious mistakes.

Figure 1. Size of assets of nationalized enterprises in Russia, billion rubles.

These semi-state business structures continue to operate under real market conditions: they enter into commercial contracts with suppliers and consumers, engage in marketing and advertising. This is not imitation, but full-fledged market activity. Moreover, in a number of sectors, the Russian economy demonstrates a higher degree of «marketness» than some European countries. For comparison: Russia’s consolidated budget for 2025, including the federal and regional budgets as well as extrabudgetary funds, amounts to 37.2% of GDP. In France, this figure reaches 57.1%, in Germany—49.5%, and in Norway—49.3% (data for 2024).

Even if we add the value added of state-owned companies to the Russian data, the share of the state sector in Russia’s economy would at best approach the Norwegian level but not exceed it.

When talking about nationalization, it would be more accurate to say that control over enterprises is shifting to loyal elites, not directly to the state.

Processes of statization, or rather pseudo-statization, are most evident in industry. According to the Prosecutor General’s Office, by March 2024, about 58% of lawsuits related to nationalization concerned the industrial sector. However, in the modern economy, the key role is played by the dynamically developing service sector, where the state’s influence remains limited. This applies not only to services for individuals but also to business services provided to enterprises and organizations. Most of these services operate under market conditions and in a competitive environment.

At the same time, monopolization is intensifying in the Russian economy, achieved not only through control over individual markets but also by creating vertically integrated holdings that cover both related and sometimes distant industries. Examples of such structures include «Rusagro,» Novolipetsk Steel (NLMK), and «Demeter-Holding.» Among recent cases, one can highlight Wildberries: in September 2025, the company «APR City/TVD,» part of the Wildberries holding structure, acquired 100% of the shares of the international airport of the capital of Ingushetia, the city of Magas.

Thus, there is no mass and consistent statization of the economy in Russia.

Foreign Trade, Price Regulation, and the Challenges of «Gosplan 2.0»

One of the key conditions of a command-administrative economy is the nationalization of foreign trade. However, under sanctions pressure, the authorities do not seek to establish a state monopoly on foreign trade activities, as this would create an obvious target for new sanctions. On the contrary, to support parallel imports, Russian authorities have organized numerous bypass channels across the border. Through these channels, not only chips and equipment necessary for the defense industry enter the country, but also everyday goods—from smartphones to household trifles.

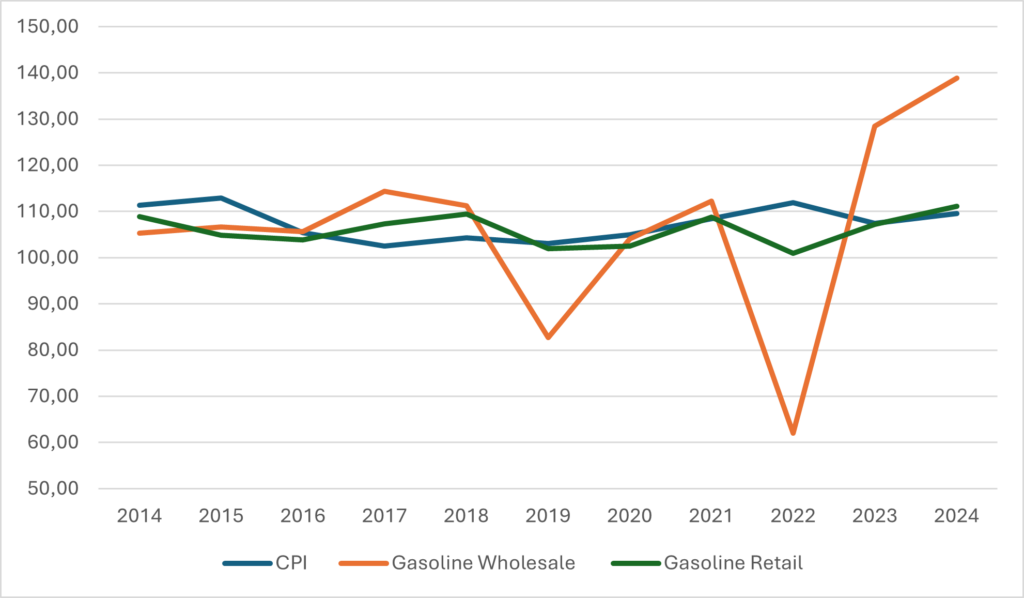

As for price regulation, there are also no grounds to speak of qualitative changes here. Although price controls are intensifying, in most cases they remain market-based, even if limited to a certain corridor. An example is retail gasoline prices (Fig. 2), which show fluctuations generally characteristic of market conditions. The only restriction is their compliance with the level of official annual inflation, beyond which they are deliberately not allowed to go.

Figure 2. Dynamics of gasoline AI-95 price growth and the consumer price index by year in Russia (calculated by the author based on Rosstat data)

The graph clearly shows that over the past 11 years, retail prices for AI-95 gasoline have rarely exceeded the level of annual consumer inflation, unlike the more significant fluctuations in wholesale prices. Over this period, retail gasoline prices rose by 89.9%, while the consumer price index increased by 118.5%. Thus, the growth in retail gasoline prices slightly lags behind the official inflation rate but significantly outpaces the growth in wholesale prices, which rose by 61%.

It is worth briefly examining the concept of «Gosplan 2.0,» proposed several years ago. It assumes that modern information technologies allow for the effective management of numerous industries and enterprises, coordinating their plans and programs with each other. In particular, Sergei Glazyev actively speaks about this from the highest podiums. Theoretically, the concept seems feasible: one can come up with many equations, fill the coefficients with information, and use them to easily forecast the market fluctuations, select planned tasks, and form balancing prices. However, in practice, implementation runs into the hierarchy of management, since state enterprises are unable to fully control even their subsidiaries. In modern management, there are simply no real tools for this.

The above indicates that the movement toward the Soviet economic model is happening extremely slowly (for objective reasons). For every supporter of building such a system, there is an opponent hindering the process.

Is a Gradual Transition from a Market to a Planned System Possible?

In Russian history, similar transformations occurred twice: from 1917 to 1929—from a market to a command system, and in 1991—from a command to a market system. Both processes were coercive in nature and accompanied by a significant drop in living standards. In both cases, the state was forced to adjust its ambitious plans. In the 1920s, this led to the introduction of the NEP, and in the 1990s—to mass lending to enterprises from the state budget, which provoked hyperinflation: in 1992, it reached 2509%, and only by 1994 was it reduced to an acceptable level. These examples are well known to Russian managers, and they are unlikely to follow them.

The Russian elite is now looking primarily at the Chinese experience, which, in their opinion, demonstrates a successful gradual transition from a planned to a market economy without serious upheavals. However, there are no reverse examples in history—of a successful gradual nationalization. A rapid transition to a command economy is fraught with risks and will face significant resistance, while a slow one requires a long-term and meticulously developed plan implemented simultaneously at multiple levels. If such a plan existed, it would undoubtedly have already surfaced. This means it simply does not exist.

Another important aspect indicating that Russia is still very far from a socialist mechanism is the state of the labor market. Over the last three years (2022−2024), wages in Russia have grown by 56%, significantly outpacing consumer inflation, which amounted to 32% over the same period. This growth is driven by an acute shortage of labor and has a distinctly market character. Unlike socialist methods based on coercion, such mechanisms are absent in Russia.

Even in the sphere of military conscription, where a state coercion mechanism is initially provided, a financial incentive model is actually used. Mobilization is carried out not through compulsory service but primarily through monetary motivation of volunteers, which essentially turns it into a market transaction for the buying and selling of labor. A similar situation is observed in the military-industrial complex (MIC). There is no coercion to work at MIC enterprises, and attracting employees from the civilian sector occurs through high salaries, which is also an exclusively market mechanism.

A comparison of the current situation with the NEP, which is often made, shows that the modern Russian elite, unlike in the 1920s, has actively taken the lead in the process of market accumulation of income. An official holding a high position receives not only power but also the opportunity to create market structures that contribute to personal enrichment. This is confirmed by numerous criminal cases involving the confiscation of significant assets that could not have been appropriated without the involvement of the entire management system. And if in the 1920s the party leadership was forced to watch as private entrepreneurs accumulated capital, in modern Russia the enrichment process is led by the ruling elite itself, and this practice has been enshrined as the norm. At the same time, opportunities for economic growth for those not integrated into the administrative system are significantly limited.

Thus, we are faced with a market economy—albeit distorted, monopolized, and permeated with corruption, but still retaining market features. Analyzing Vladimir Putin’s actions, one can notice that he oriented himself not toward Stalin or Mao, but rather toward figures like Silvio Berlusconi and Juan Perón. In particular, the scheme by which Putin eliminated independent television in Russia largely resembles what Berlusconi did with Italian TV channels.

Vulnerabilities of the System: From Corruption to Demographics

In modern Russia, there are no prerequisites for forming a socialist distribution system, and they are unlikely to appear as long as Vladimir Putin remains in power. However, under conditions of a relatively low level of well-being, social support for the population remains necessary to prevent social unrest. This practice inherited from the Soviet period remains relevant today.

This system has many shortcomings. First, it is poorly applicable to such a vast country as Russia. Geographic expanse and varying regional potentials lead to differentiation not only vertically (between the center and the regions) but also horizontally (between regions), making uniform provision of «socialism» for all impossible. Second, the ruling elite, in a state of «age-related overripeness,» actively resists renewal and co-optation of new cadres. Third, the shrinking working-age population increases pressure on the labor market, requiring further wage growth. Finally, in the complex, hierarchical, and multi-industry society of the 21st century, it is impossible to build quasi-feudal relations characteristic of the 19th century. And closing off the country will inevitably lead to the Russian elite’s standard of living lagging behind that of developed countries, which no one wants either.

The main threat to this system lies in the contradiction between market mechanisms and attempts to eliminate their key element—competition. At the same time, the system absorbs enormous resources directed toward the military-industrial complex and corrupt consumption. It is difficult to predict exactly where and when this system will fail, but its stability is obviously declining with each year.