In June 2022, Russia adopted a new law on oversight of the activities of ‘foreign agents’. From today’s perspective, the first version of the 2012 law on foreign agents looks like a vegetarian option. Today, officially registered non-profit organisations (NPOs), informal associations of citizens, media outlets and individuals can be listed as foreign agents. The 2012−2013 version of the law was criticised primarily for its broad definition of ‘political activity’, which covered any public activity. Foreign influence, however, was identified by the presence of funds in NPOs’ accounts coming from non-Russian sources. The 2022 version of the law not only broadens the scope of those who can be recognised as a foreign agent but also applies the all-encompassing logic to the definition of foreign influence, which from now on can be any kind of ‘foreign influence’.

The Russian political regime has now reached the stage of complete mistrust of any independent activism. Let’s try to identify how the NPO community itself and the state’s interaction with civil society organisations (CSOs) have changed.

A fifth column

In the early 2000s, the Putin administration had a strategy of keeping CSOs close and cooperating with them ostentatiously. In 2001, a so-called civic forum was established by the Kremlin. The forum’s goal was to bring professional regional NPOs together in order to ‘develop mechanisms of interaction between civic organisations and the government’. The idea of this endeavour fit well with the public discourse that accompanied the first years of Putin’s presidency, namely the consolidation of efforts to strengthen the state and improve the quality of life. The forum, which comprised 5,000 participants, did not, of course, develop interaction mechanisms. It probed the ways in which the new Russian authorities could work with CSOs. At the same time, the political expediency of participation in the forum was questioned within the community itself.

The demonstration of openness and attempts to gain the loyalty of civil society leaders ended after the Orange Revolution in Ukraine and other colour revolutions in Georgia and Kyrgyzstan. Researchers note that the involvement and mobilisation capacity of civil society and, in particular, youth organisations in the watershed events in Ukraine and other post-Soviet countries were pivotal for the Kremlin. Since then, the regime has revised its strategy towards CSOs, shifting from cooperation to distancing and discrimination.

In the 2000s, the authorities sought to take control of youth movements. Alternatively, they established subordinate government-organised non-governmental organisations (GONGOs) to replace their core activities. During that period, the Kremlin created GONGOs on all flanks of the ideological-activist spectrum. This was done in order to counterbalance the small number of publicly active parties, ranging from the National Bolshevik Party to Youth Yabloko. The highest-profile youth project was the Nashi political youth movement. The quasi-social movements were aimed at channelling activity into a controlled organisational framework, to divert the support of the target audience for opposition movements and organisations, and to marginalise and discriminate against independent public activity.

At the same time, the trope of a fifth column was gaining ground. The notorious plot of a fake rock containing a hidden spying device led to highly publicised accusations by the state against experienced and reputable non-profit organisations (the Moscow Helsinki Group, the For Human Rights movement and the Memorial society). Moreover, it created room for distrust in independent public activity with alternative sources of funding other than the Russian state. At the time, there was no direct crackdown on CSOs, as modern autocracies are interested in having control over their opponents and upping the ante through the marginalisation of public activity. This marginalisation was carried out by pro-government organisations. One example of this was the Nashi campaign against opposition members, including leaders of CSOs, who were presented as fascist collaborators.

In the early 2000s, the government decided to standardise NPO activities. The Federal Registration Service (FRS) was vested with oversight functions. The 1996 law on non-profit organisations provided for a variety of organisational forms and did not impose strict criteria on the internal structure of NPOs or on the mode or format of their work. When the FRS started interfering in their affairs, the situation began to change: the agency conducted regular inspections of NPOs, which became a bureaucratic ordeal for them. A study of the FRS’s implementation of administrative decisions to inspect NPOs in 2008 showed that the criteria for and form of inspections were unclear for non-profit organisations, while the agency’s allegations were formal in nature (pertaining, for example, to a lack of notification about a change in the organisation’s address, failure to report to the FRS on assets used, etc.). At the time, NPO managers noted that they were ‘experiencing increased administrative interference’.

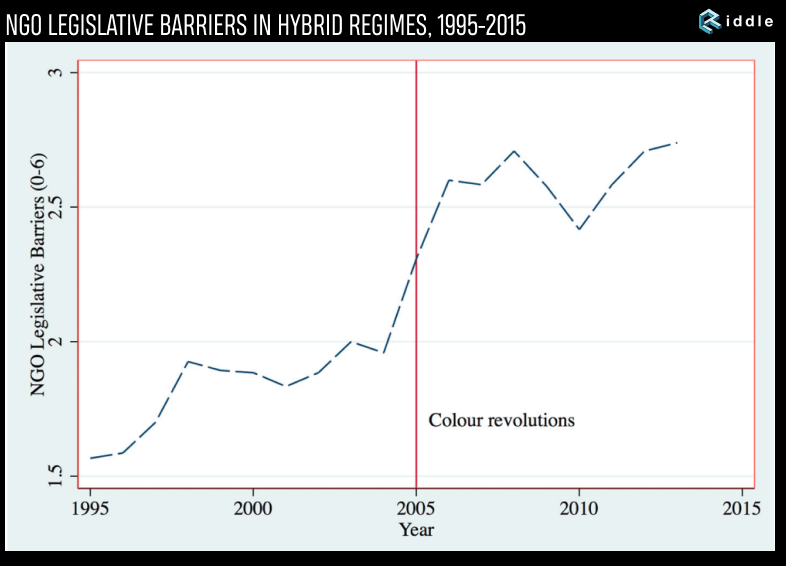

According to research, legal and other organisational barriers are a common tool used by autocracies to exercise control over opposition or civic associations. Leah Gilbert and Payam Mohseni point out that such domestic legislative barriers are a response to external conditions. The authors show that, between 1995 and 2015, organisational barriers to NPOs in authoritarian regimes were tightened everywhere. The restrictions scaled up significantly after the wave of ‘colour revolutions’.

Source: Gilbert, L., & Mohseni, P. (2018). Disabling dissent: the colour revolutions, autocratic linkages, and civil society regulations in hybrid regimes. Contemporary politics, 24(4), 454−480.

Foreign agents and a schism

Despite mounting legislative barriers, the first decade of the 2000s can be called productive and successful for Russian NPOs. During this period, large-scale human rights projects were implemented, and civil expertise and public oversight were developed. Several human rights organisations from outside Moscow united to form the Agora association while Golos (a movement for the defence of voters’ rights) developed and published a draft Electoral Code of the Russian Federation. All this was made possible thanks to a rich network of organisations, their close cooperation and the availability of non-governmental funding on a scale that made such projects possible. The largest donors to Russian non-profit organisations at the time were international non-governmental foundations (the MacArthur Foundation, the Ford Foundation, the Soros Foundation and the Mott Foundation) and foundations with a focus on policy and governance (the Bell Foundation, the Friedrich Naumann Foundation for Freedom, the NED, the Dutch Fund for Regional Partnerships [NFRP]/Matra and USAID).

The very fact that an NPO received a grant from a foreign foundation was indicative of its professionalism and quality organisational culture. Successful grant applications meant that the NPO had a professional staff of qualified non-profit managers, efficient workflow management and public transparency.

A new phase in the Russian autocracy’s clamping down on NPOs was harbingered by the foreign agent law, which in practice eliminated any foreign funding and increased funding by the Russian state manifold. The law on foreign agents and the subsequent law on ‘undesired organisations’ was a real external shock which dramatically reshaped the NPO community. Studies of the law’s impact on the community revealed that it had increased the existential risks for NPOs. Many organisations were forced to divert their internal resources from ongoing projects and public activities to their own security. They had to monitor outflows more closely in order to avoid pretexts for their inclusion in the register of ‘foreign agents’. When the first NPOs were put on the list, it became clear that the main problems were not the fines per se but rather the red tape and the fact that the Ministry of Justice as a relevant agency could interfere in their activities and thus impact their performance. Being enlisted engendered fines, closer attention by inspection agencies, and more frequent and detailed reporting.

Repressive laws against NPOs became a trigger for organisations to choose their own trajectories of adaptation. According to a report by the Civic Chamber of the Russian Federation, the number of NPOs in Russia declined by 33% between 2012 and 2014. For the first time in many years, closing down, including at their own initiative, became a common way for NPOs to solve their problems. At the same time, some of the organisations which were shut down continued their activities without forming a legal entity, in order to stay off the state’s organisational radar. However, the majority of NPOs decided to adapt to the new conditions and refused foreign funding. Research shows that active and well-known regional organisations were most severely affected by the law. The state proved to be uncompromising when it came to adherence to the law. The confrontational strategy of some NPOs had negative consequences for them in the long run. It was a warning for other organisations that they should accept the new rules of the game ASAP. The law not only had an organisational impact on NPOs but also changed the vibe in the community: an organisation’s very attitude to the law was a manifestation of its loyalty or disloyalty to the regime. Former partners in joint projects stopped inviting one another and attending each other’s events, and mutual accusations of venality or short-sightedness became commonplace in discussions within the community.

In parallel with the schism within the non-profit sector over the law on foreign agents, there was also a split over attitudes towards state funding. In ten years, the state increased funding for NPOs from 1 billion roubles in 2011 to 11 billion roubles in 2020, and this only through the Presidential Grants Fund. Since the regime perceived independent activism and funding from foreign sources as dangerous, it replaced all funding for NPOs with its own resources, putting social activism under organisational control. Representatives of the non-profit sector note that the presidential grants provided sources for project implementation but at the same time created dependence on and subservience to the state, including in terms of the selection of eligible topics in grant applications. Presidential grants or funding from regional authorities strongly influenced the way the state interpreted NPOs’ public activities. A public statement contradicting the administrative position was perceived as a manifestation of disloyalty, which affected the allocation of funding for social projects to NPOs.

The situation when it came to the foreign agent law and almost exclusively state funding of NPOs contributed to the polarisation of the community: for some, it was an excuse to politicise what was happening and to publicly express their disloyalty to the regime, while others adopted collaborative tactics to implement projects and protect the rights of their target groups. The large coalitions of NPOs that had existed prior to 2012 as a standing practice of interaction within the community became unthinkable due to the fact that loyalty to the regime had become a barrier to entry.

Quasi-activism and the role of the transmission belt

The new version of the law on foreign agents shows that civil activism of all kinds, not only that of NPOs, was trampled on. Moreover, there are tendencies not only to use NPOs in the state’s interests but also to replace the civil society community with state-controlled non-governmental activism.

Illustrative examples include the establishment of the youth social movement Bolshaya Peremena (Great Change), whose supervisory board is chaired by Vladimir Putin, and the revamping of the Znaniye (Knowledge) Society, whose supervisory board is headed by Sergey Kirienko. Both examples indicate that the state’s current aim is to replace the non-profit sector (already burdened by the marginalisation of professional NPOs, organisational checks, foreign-agent restrictions and exclusively state funding) with state-controlled institutions which will operate as transmission belts. Whereas in the early 2000s GONGOs existed alongside real NPOs and competed with them, in 2022 GONGOs are becoming the state’s main leverage for managing civil society.

The political system in Russia is seeking transmission belts at the moment because of the regime’s transformation. With the outbreak of war in Ukraine, the regime has begun its movement towards a closed autocracy, which requires a realignment of relations between state and society. Christopher Heurlin wrote that autocracies with more stable institutions tend to replace genuine civic activity with organisations which are direct extensions of the state. Typical examples are China or the Soviet Union, with their extensive networks of party transmission belts such as trade unions and environmental, recreation, sports or volunteer associations. The transmission belt is not meant to simply channel the potential of civic activism in a controlled manner. It is to completely replace independent activism with state-controlled non-governmental activism.

Putin’s regime has historically been distrustful of NPOs, so it is interested in making NPOs a direct extension of itself for greater sustainability. If Bolshaya Peremena and Znaniye prove to be more than isolated cases, we can expect other quasi-civic state-controlled organisations that are part of the power vertical to emerge in the future.