In early May 2022, the Project independent media outlet reported that the Kremlin had decided to curtail the use of the term ‘denazification’ in the media, one of the key words used to justify Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. Since only a few knew about Putin’s plans, spin doctors did not have time to work out alternative justifications for the invasion and assess how well they resonated with the public. Despite its constant presence in the media, the meaning of the term remained a mystery to Russians, and Russian propagandists faced a dilemma: it was impossible to ignore the words uttered by the president, but it also made no sense to reiterate them. This example illustrates the vulnerabilities of propaganda machines in authoritarian regimes, especially when propaganda does not strike a chord with the mass sentiments of citizens.

The Russian media landscape has changed dramatically during Vladimir Putin’s rule: since 2012, the regime has become increasingly aggressive towards dissent and has ramped up control over the media. By February 2022, the Kremlin not only controlled the ‘commanding heights‘ – TV channels and the most popular periodicals — but also monopolised key social media, which allowed it to easily spread stories about ‘Nazis’ among the Ukrainian leadership on the eve of the invasion. But despite its absolute monopolisation of the information space inside Russia, the propaganda potential is far from limitless.

To better understand the link between Kremlin propaganda and the mass sentiments of Russians, we put together a corpus of messages in the Russian traditional and social media that were in one way or another related to the war in Ukraine. The corpus comprises about 18,000 messages broadcast from February to July on television and about 400,000 messages that appeared in social media in July 2022. Our aim was to track both the frequency of use of individual terms and phrases in propaganda and their presence in social media discussions. The results show that the propaganda machine’s successes in some areas are offset by failures in others. Read more about the results in the monitoring report.

The eco-system of Russian propaganda

Propaganda is one of the favourite tools by which modern autocrats keep potential mass unrest under control at a relatively low cost. Today’s propaganda machines resemble Cerberus, the multi-headed hound. They control both traditional platforms (television and print media) and new media outlets in order to put forward a uniform narrative. They operate with both facts and outright fabrications. Finally, not only do the anchors on key TV channels work for the propaganda machine, but so too do whole armies of bots and trolls on social media.

Russian propaganda is no exception. RAND experts Christopher Paul and Miriam Matthews once described it as a ‘firehose of falsehood‘ pointing to the incredible speed and volume of disinformation, as well as its lack of coherence in terms of presentation and interpretation. The general policy is set at weekly meetings of the Presidential Administration with the heads of key channels, as well as by means of ‘gag orders’ [temniki] as to what news to cover and how. Since it is impossible to control thousands of media workers manually, the general approach is not to exclude ordinary journalists but to rely on their improvisation in applying personal interpretations of the Kremlin’s political line. Often, the images on the screen are inconsistent with the mandated line, but convey important news content that attracts journalists’ attention. This was the case, for example, with the ‘little green men’ – Russian soldiers with no insignia in Crimea — accidental phone footage of whom flooded the state media, even though the Kremlin was at the time denying the presence of the Russian regular army in Crimea.

Russian propaganda actively exploits the specific nature of Russians’ media consumption patterns: on the one hand, television remains its mainstay and is still the key source of information for 62% of Russians according to a 2021 poll (89% claimed to watch television at least once a fortnight in late 2021). However, beyond television, the Kremlin’s propaganda machine covers an extensive network of social media outlets, including public pages on Odnoklassniki and VKontakte (most popular Russian social networking sites), Telegram feeds, video hosting sites, and even platforms like TikTok. Since spreading the same information on social media alongside the traditional media adds credibility and reliability to the propaganda, in Russia’s case we can speak of an entire propaganda eco-system.

Finally, in the last decade, Russian television has developed a peculiar format that combines delivery of ideologically loaded information with entertainment. Its aim is to attract an audience that is not very engaged or is even sceptical. Unlike infotainment (a genre that relies on entertainment formats to deliver news to an apathetic audience or simply to make a profit), agitainment uses globally popular media formats (such as talk shows) to impose an official policy. Within this format, the Kremlin propaganda successfully engages pseudo experts to disseminate misconceptions among not only Russian-speaking but also international audiences.

Thus, the Kremlin’s propaganda model includes several components. First, absolute control over commanding heights in the media space, i.e. the most popular means of communication and platforms, which allows a massive infoglut to be created when necessary. Second, agitainment reaches not only the regime’s staunch supporters whose position will not change after another of Vladimir Solovyov’s shows, but apolitical citizens as well. Finally, the lack of any consistency whatsoever and the cascades of contradictory explanations result in citizens’ mistrust of any information sources and a cynical attitude towards media content. Some of these characteristics became obvious after 24 February.

‘Where have you been for the last eight years?’

Russian propaganda proved its effectiveness long before the invasion of Ukraine: in the early 2000s, when the Kremlin still had little control over the media space, even the events of the Orange Revolution of 2004−05 did not negatively affect Russians’ attitudes towards Ukrainians, according to the Levada Center. The situation changed in late 2008, when the military conflict with Georgia and the ‘gas war’ boosted the percentage of Russians who had a negative attitude towards Ukraine to 62%. A second spike in negative attitudes occurred between March and June 2014. And while public opinion about Ukraine was still divided in November 2021 (45% positive assessments against 43% negative), by February 2022, the percentage of the latter was 52%, and by July — 66% (the peak for all years of observation). The upsurges in negative attitudes are synchronous with the Kremlin’s major information campaigns against Ukraine.

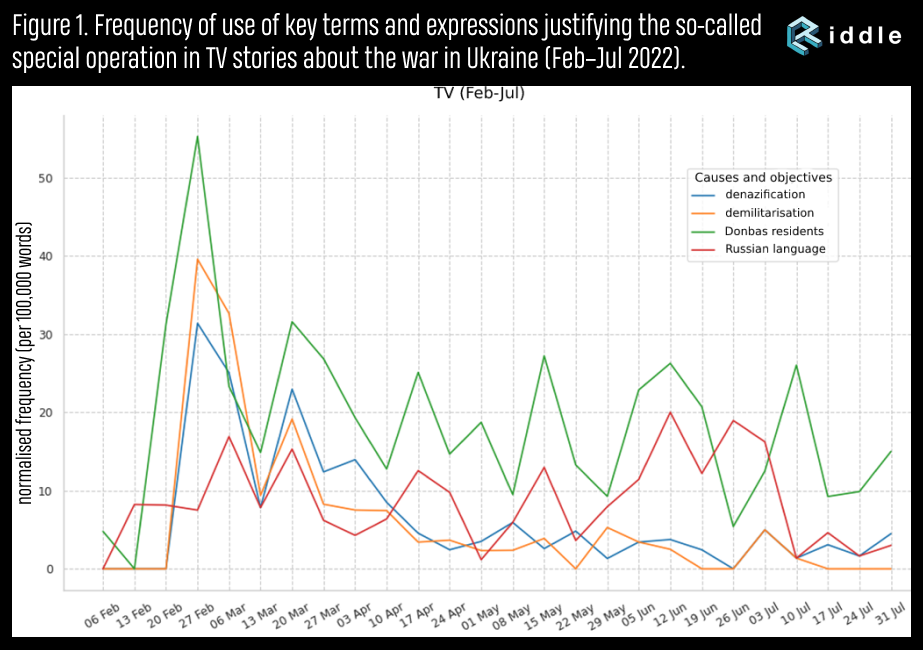

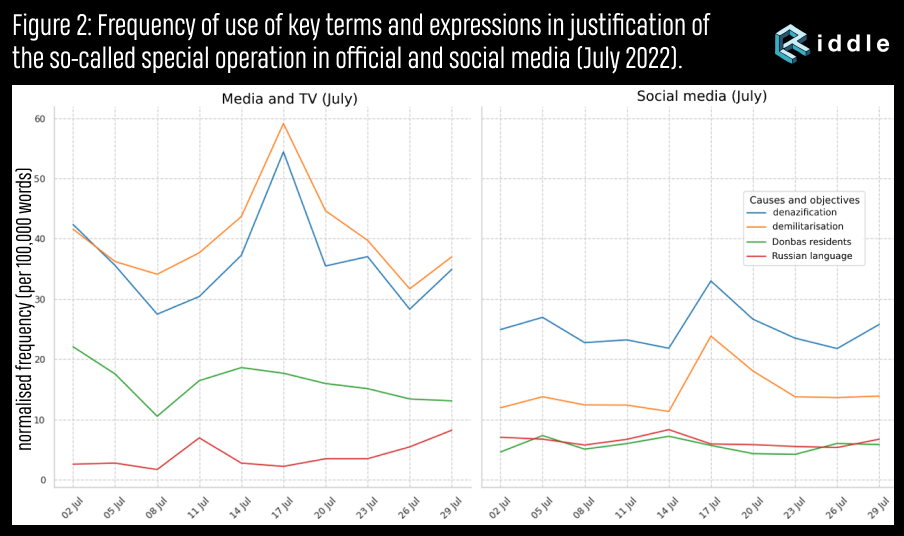

The campaign on the eve and aftermath of February 24, 2022, however, has its own peculiarities: as our analysis of TV and social media messages related to the war against Ukraine shows, the propaganda has difficulty justifying the goals of the ‘special operation’ and promoting them in the media. First, as mentioned above, problems arose with the use of key terms (‘denazification’ and ‘demilitarization’): the frequency of their use on Russian television increased dramatically after the special operation began, but dropped two weeks later (Figure 1). By June 2022, these words had almost disappeared from the TV presenters’ vocabulary. The use of the expressions ‘protection of Donbas residents’ and ‘protection of the Russian language’ (in different variants) remains stable, reflecting the belief that these ideas resonate more with the mass public. These expressions are updated before public holidays (Victory Day on 9 May and Russia Day on 12 June) and after a significant advance by the Russian Armed Forces at the end of June.

Although ‘denazification’ and ‘demilitarization’ had all but disappeared from TV by June, officials and the official media were forced to continue using them, which allowed us to directly measure the extent to which these terms resonated with the sentiments in social media (due to certain limitations, we were only able to extract data on the latter from July onwards). Figure 2 shows the normalised frequency of usage of the main justifications for the invasion in the traditional and social media (90% of posts and comments on Odnoklassniki, VKontakte and Facebook). Thus, we see that all four keywords/phrases are used many times less frequently by social network users than by official media. Considering that there are many bots and trolls among the former, the true public response is likely to have been even lower. The upsurge in usage (in the week of July 11−17 in the chart) coincides with high-profile statements by officials (in this case, Senator Klishas’ statements about the situation with the Crimean bridge). Interestingly, however, the ‘protection of Donbas residents’ does not strike a chord with a wider audience on Russian social media.

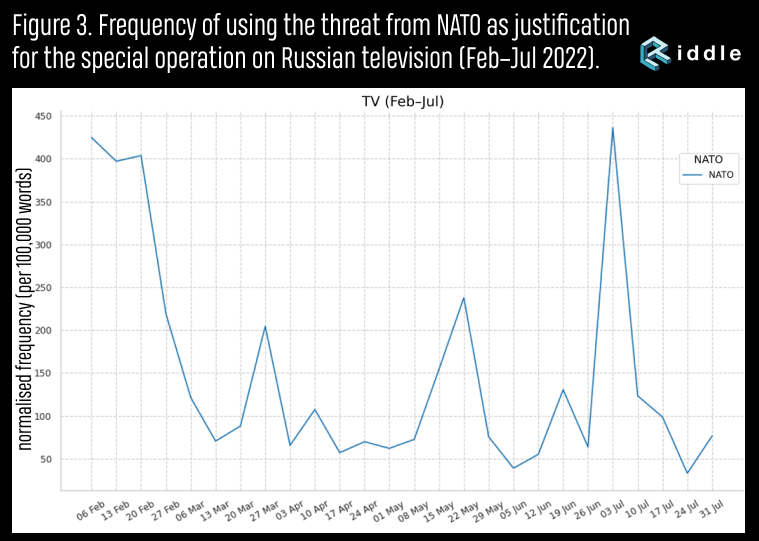

Against this backdrop, the propaganda uses fixed phrases and links the need for a special operation to a response to a threat from NATO: the volume of reports about NATO was quite high already on the eve of the invasion, giving way to the justification voiced by President Putin on 24 February. Nevertheless, the number of stories about confrontation between Russia and NATO against the backdrop of the war in Ukraine remained quite high and increased ahead of milestone events (such as Victory Day and the NATO summit in Madrid in late June).

We can conclude that, on the one hand, the eight years of the Kremlin’s propaganda rehearsal before the war have not been in vain: the aggressive anti-Western rhetoric and the longstanding information campaign against Ukraine have provided important support for the special operation. On the other hand, the new terms and meanings that the Kremlin has tried to assign to the special operation have apparently not yielded any significant increase in support compared against, for example, the 2014 Crimean campaign. The mass repression in the immediate aftermath of the war suggests that the Kremlin may not have counted on support. The main objective was to suppress any critical voices, and if this strategy had been successful, no additional efforts to justify a special operation would have been necessary. However, these hopes have been futile.

Trust no-one

In addition to broadcasting the official version of events, the key propaganda task is to create significant obstacles to finding reliable information. Here, the mission unfolded on several fronts: first, the State Duma immediately passed laws introducing administrative and criminal liability for ‘discrediting’ the Russian Armed Forces and spreading so-called fake news about the Russian army. Russian propaganda uses the words ‘disinformation’ and ‘fakes’ in reference to dissent and independent media in order to undermine the credibility of these sources. Their frequency increases at watershed moments in a military campaign such as the withdrawal of Russian troops from Bucha or the capture of Mariupol. This rhetoric is very familiar to the Russian audience and is part of the official discourse about a ‘hostile West’ and a ‘fifth column’ undermining stability from within.

Social media audiences proved quite receptive to the rhetoric of searching for internal enemies, although the words ‘foreign agent’, ‘defamation’ and ‘disinformation’ do not appear too often in discussions of the special operation. Over July, they gradually gained importance, accompanied by regular updates to the list of foreign agents and the opening of new cases under the relevant articles. More illustrative is the dynamics of the use of the term ‘fake’ (Figure 4): while surges in use in the corpus of media reports are related to individual events, social network users often spontaneously discuss topics related to fake news. Overall, the rhetoric of discrediting positions different from the official one lays fertile ground for distrusting all sources.

The euphemism game

Another frequent propaganda technique has been the appropriation of the descriptive terminology referring to the ongoing events. For example, the term ‘war’ is used in TV programmes quite often, but not in reference to the special military operation. It is used with reference to Russia: it is claimed that there is an information war and war of sanctions waged against the country, that there is a threat of world war due to the actions of the Ukrainian leadership and Western countries, and the emphasis is placed on the fact that Russia’s actions are only retaliatory. A similar situation is observed with the word ‘crisis’: independent and opposition media outlets describe the situation in the economy in this way, while official television channels speak of the ‘gas crisis’ in Europe, ‘food crisis’ in the world or ‘crisis’ in Ukraine (Figure 5). Thus, the struggle is not only over the territory, but also over the meaning of the words used to describe the situation.

Is the propaganda stalled?

An analysis of the key words in the Kremlin’s propaganda rhetoric regarding the special operation shows that, on the one hand, years of indoctrination, undermining trust in independent sources of information and a negative image of the Ukrainian authorities and Ukrainians have paid off: some conceptual units, like ‘protection of Donbas residents’, that are not based on facts have been well-received by Russians. Other terms, however, did not strike a chord with the public and made propagandists review their strategy.

On the one hand, this shows that the Kremlin propaganda machine is flexible enough to recognise and respond to key challenges. The editors of the main TV channels are well aware of the shrinking of their audience since February 2022, a trend that the Romir agency captures. Sociologists have also recorded a gradual decline in Russians’ attention span for the war with Ukraine at least before mobilization announced on September 21. This event could not help but force propaganda to change emphasis, especially against the backdrop of the absence of any success on the part of the «allied forces». After September 21, the Kremlin once again began to promote narratives about the «collective West» and «we do not abandon our own,» but the initial reaction to the mobilization turned out to be rather negative. The concepts of eight years or six months ago have not been replaced by new meanings. According to Meduza’s sources, a manual for the media has already been prepared to cover the mobilization. Significantly, this manual instructs the media to draw on narratives about NATO and the people of Donbass, topics that we show resonate more with public opinion. At the same time, the goals of the «special operation» — narratives that, as we show, did not cause a resonance and were abandoned — were generally excluded from it. Now propaganda faces a much more difficult task — to justify mobilization, which, unlike war, is not an abstract process taking place somewhere far away, but directly affects the lives of Russians.

Studies have already shown that blatant and long-lasting propaganda can have negative long-term effects for the legitimacy of authoritarian regimes. In addition, in response to blatant propaganda, citizens — and social media users in particular — may often multiply their efforts in search of reliable information. Increased repression or censorship also has its side effects. Moreover, polls show that Russians are far from unequivocal in their assessment of the policy to block Internet resources. Protracted hostilities, worsening economic conditions and direct intrusion of the regime into the privacy of citizens raise the question of whether Russia’s Cerberus of Propaganda has the legs for the long-distance run.