When discussing the vast scale and impact of “Fake News,” it is worth keeping in mind that the term itself has become a politically charged rhetorical device, which does not necessarily make it the best descriptor for a phenomenon that is swiftly changing how the world digests information. Nevertheless, the term has caught on. So it can serve as an easily recognisable shorthand, though it is at most an umbrella term for various distinct types of disinformation and misinformation.

The world’s leading universities are opening research programs looking into this, while governments and international organisations have made repeated announcements that they now consider the pollutive qualities of disinformation and misinformation a major contemporary threat.

Many institutions and companies are creating specialised services focusing on how to counteract it — there’s a noticable rise in fact-checking sites, and rising political pressure on social media sites like Twitter and Facebook to address the issue on their platforms. The President of the United States, all the while, uses the term “Fake News” broadly and repeatedly in his fight against political opponents, often in a wide variety of contexts.

Journalists, who just yesterday were anticipating another wave of dismissals due to their industry’s continuing crisis when it comes to finding a financial model, are looking to the future with a glimmer of hope, believing (and rightly so) that they have a special role to play in the response to these new challenges.

In fact, the term “fake news” describes a broad variety of communications phenomena and practices. Some of them were known and well-studied long ago (just like the ways to counteract them). But some practices have turned out to be new, specific mutations created by the digital revolution. The concept of fake news also describes a small but very worrying group of “weaponised” communication technologies, brought into today’s Internet reality from the dusty corridors of the Cold War. These seem to be more dangerous and malicious in the new reality than their original creators could have imagined.

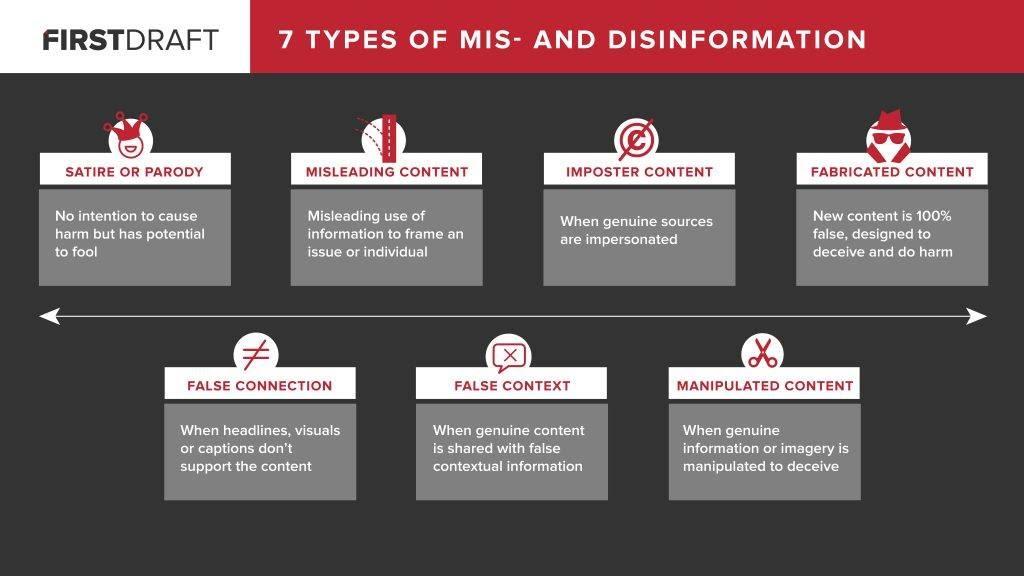

A classification developed by the NGO FirstDraft is often used to describe the term “fake news”. The reference system in this chart represents “harmfulness” and “premeditation.” Less harmful varieties feature on the left of the chart, while those on the edges have more to do with “premeditated” content, and those in the middle are mostly the result of mistakes or misconceptions (more misinformation than deliberate disinformation). At the same time, any form of “false” information poses a threat, even satire: Jokes that are misunderstood or taken at face value may lead to as great negative consequences as deliberately “weaponised” disinformation.

Deception and propaganda

Being fallible and being deceptive are two very different, very human traits. Deceptive communication, one way or another, is present in all disciplines of communication science – be it interpersonal, corporate, or strategic deception at the state level. Deception is a natural (though regrettable) practice.

Deception — disguise, imitation, false leads — is a normal element in the military world, and in recent years also in the corporate one; when the lives of soldiers (managers, products, services) and civilians are at stake, when the cost of a mistake almost always translates into mass deaths (or dismissals). The desire to outsmart an opponent, to intimidate them and cause them to make false moves, is justifiable in the modern world full of communications, and in certain circumstances is better than the large-scale use of direct force.

Strategic deception is possible without direct military conflict, but as the second half of the 20th century demonstrated, it is undesirable: Instead, nuclear-armed countries made efforts to increase mutual trust (by renouncing deception and following the principle of “trust but verify”). Large-scale deception of an opponent who has the power to blow to smithereens not only the enemy but all of civilisation is a dangerous and unsettling business. During the Cold War, when tension would occasionally jump to the “finger on the button” level, opposing countries developed the principle of deterrence: To prevent your opponent from making a tragic mistake, the expected retaliation should be so obvious and painful that they will prefer to do nothing instead of acting.

Meanwhile, the peculiarity of what we are now discussing as fake news is not deception and lies as such, but intentional use of such practices in national and, ultimately, global mass communication. This is what causes crises and neurotic anxiety within society. That is to say: Accidental deception, unintentional use of lies and self-deception that affects others are unpleasant, and our brains have a built-in mechanism of doubt and critical analysis. But a strategically constructed and employed deception trap is a weapon, which is harmful not only to those it targets, but possibly to everyone, including its creators.

The other side of trust

The main damage from fake news – both as a phenomenon and as a concept – comes from the destruction of public trust, especially in the country’s independent mass media. All countries, not only democratic ones, have some form of such institutions: Together with an institutional monopoly on violence, they seal the foundations of the social contract.

The credibility of information, especially when it comes from the authorities, is a “double-edged sword”, which has been in the hands of mass media and journalists (or party ideologists in the USSR and China, or ayatollahs in Iran) for many years. Recent decades have demonstrated that totalitarian lies and attempts to isolate citizens cannot hold together the foundations of a state. Unfortunately, however, the parallel processes of building trust, and its destruction, are also happening in democratic countries. Surprisingly, the reasons for the decline in trust are almost the same as those that support it: by criticising the authorities, mass media affect the relations between politicians and their electorates (which are not always based on common sense), and, although they seemingly fulfil a “purifying” social mission, they simultaneously reduce their credibility in the eyes of individual groups.

The outcome of such a two-track process is now sitting in the White House, insulting the New York Times and CNN, to the utter delight of that part of his electorate whose interests and habits have been affected by the impenetrably liberal position of the newspaper and the pro-Democratic Party focus of the TV channel. This mechanism, described by Eli Pariser in his book The Filter Bubble back in the mid-noughties, has been amplified by social media.

At the same time, digital distribution of information has introduced another problem (or, to be more accurate, aggravated it). In the good old analogue world, the number of information sources was limited by both political and economic factors. The number of newspapers and magazines was defined not only by supply and demand, but also by the physical possibilities for their production and distribution. The number of analogue TV channels and radio stations was limited by the restricted number of frequencies, distributed by the state. The structure of editorial mass media in itself was an additional limitation: a multi-level model, in which the editor played the role of a gatekeeper, deciding whether to allow a certain message to reach the audience. But the theory of traditional communication channels, formulated by Kurt Lewin in the 1940s, turned out to be defenceless in the face of technological development.

The liberation of Authors via Internet publishing, and the mass media’s (frankly, forced) loss of the gatekeeper role, has provoked exponential growth of sources of information, which became available to everyone simultaneously. In order to ensure continued functioning of the mass media’s traditional business model, media outlets had to constantly boost traffic on their websites and social media. Since media consumption is becoming more and more dynamic, journalists and editors are forced to rely on headlines more than ever, as this may be the only way to catch readers’ attention.

Hence the rise of clickbait: the art of creating headlines that attract readers (but don’t necessarily correspond to the meaning or the essence of the underlying text). As in the case of double-edged mistrust, clickbait poses no direct threat; however, after a while, the quantity of deceptions becomes a quality all its own, and society’s willingness to trust the messages coming from mainstream media declines — after all, they deceive us with those headlines!

The third double-edged property of the trust problem is the mass media’s disregard of the psychological traumas of the societies in which they operate. As mentioned above, with the benefit of hindsight we realised that we underestimated the risks faced in the post-communist, globalising world. There was too much confidence placed in Francis Fukuyama’s “end of history” concept, and too little thinking about potential generational conflicts – from digital inequality to societal frustrations caused by migration.

In almost all developed countries, mainstream politicians have ignored the “frustration agenda”, leaving it in the hands of populists and radicals; the situation in Russia is unique, because, although this agenda was exploited by nearly all politicians, nobody except Putin and his ideologists has managed to come up with a “Russian” version. If we remove bureaucratic language and state patriotism from the Kremlin’s rhetoric, the isolationist, anti-globalist messages, with clear traits of the “white race movement”, becomes obvious.

Mass media in Russia, in the West, and even in America noticed those messages but misinterpreted them, probably assuming that such isolationism and nationalism were developing on the “periphery” of society and were marginal. Their rhetoric opposed (or supported) various kinds of ultra-right geeks, or aggressive anti-globalists, while such attitudes were apparently shared by much wider population groups, capable of changing the electoral landscape even in very well-established and stable democracies (as the 2016 US elections showed).

Consequently, while the media were throwing mud at marginal politicians and their views, they failed to realise that they were, in fact, criticising and accusing quite significant groups in society. And those groups very quickly started doubting such media, and then started openly calling their critics “fake news”. The direct result of these mistakes is the unprecedented low trust expressed by the US public towards institutions including the mass media: Surveys show that less than one-third of respondents are ready to support journalists’ position on certain issues without hesitation.

The situation in authoritarian political cultures – Russia, for example – is further complicated by the government’s active attempts to reduce the influence of independent mass media on society. Starting from the mid-2000s, state channels started intentionally worsening the already unbalanced relations between the media and society. By tearing the delicate fabric of trust, they were counting more and more on the volume of their own loudspeakers, without expecting that their weapon against trust would also backfire. Today, it looks as though there are no more institutions of “universal trust” left in Russia.

Fake news platforms

There are several types of platforms serving the fake news phenomenon, best classified by the motivations of those who commission them, the behaviour of the implementers and the impact they have (here I will concentrate on what is happening in the United States).

Analysing fake news from the liberal point of view, we have to understand that there are cases of quality journalism or “proper activism” from the opposite side of the political spectrum too (which could serve as examples for liberals). Mutual accusations are very different in nature: While liberal criticism of fake news focuses on consumers being deceived (false information, edited information, content distortion) and weaponisation of news stories (or what we in Russia call “the atmosphere of hate”); conservative critics complain primarily about the bias of liberal news (partisanship, desire to support or highlight only political opinions they agree with) and “elitism” (not unfounded, as demonstrated above). Accusations of “liberal tantrums” have been also added recently.

The most prominent example is commercial fake news: websites created exclusively to distribute falsified pseudo-news content, which monetise traffic from social networks and use bot amplification and other tactics. The most interesting example is the fake news factory in Macedonia, but there are also purely American “news dumps”, which actively exploited the filter bubble effect with stories like “Hillary participates in cannibalistic rituals”. Organisers of this orgy of deception have no specific political preferences: They were (and some of them still are) earning money on the political polarisation of the US, where, as we know, the audience is the most valuable. Each click in Google or on Facebook brings money to the owner of a fake news website.

Ultra-partisan websites and their networks, which exchange banners and links, and used such connections to expand distribution for Twitter and Reddit botnets, could be viewed as further examples of fake news platforms. Back in the autumn of 2015, certain web analytic tools (e.g. MediaMetric) started unexpectedly showing very high reader ratings for a certain group of conservative writers and bloggers, mainly connected to Breitbart. The dominance of these extremely one-sided conservative columnists (there was no journalism there, just biting, knee-jerk anti-Hillary slogans with links to various sources with materials compromising the Democratic candidate) were so impressive that I had to do my own investigation. My findings (which later received quantitative confirmationfrom a group of researchers led by the Yochai Benkler group from Harvard) showed the presence of specific “amplifying networks” for conservative websites, in which, apart from Breitbart, there are several other big traffic generators, such as Drudge Report, public accounts on Reddit and discussion groups on 4Chan/8Chan. These unexpected “amplifiers” also included RT and Sputnik, which discretely published links to conservative resources and, presumably, were engaged in link exchange with them.

It is rare that ultra-conservative websites are caught peddling blatant lies or fabrications. Their most common methods rather fall into the categories of misinformation and misleading context – deliberate misrepresentation by the authors, who refuse to listen to arguments from the opposite side (and consequently sees the world only in one light, treating any contradiction in terms of conspiracy theories), or providing false context for the information by, for example, making comparisons using dissimilar metrics, or portraying a single incident as a trend. This form of fake news is dangerous not only because it can be easily and effectively distributed among supporters of a certain point of view (using the same filter bubble effect), but also because the main if not only weapon of criticism against liberals is accusing them of deception and distortion of information. Any “column” on Breitbart will always mention “the lying mainstream media” (or perhaps “the lamestream media”), and these messages are always amplified by online bot farms and the Fox News channel.

The third type of fake news platforms are online propaganda resources, among which we can also list RT.

Propaganda in a Fake News World

Propaganda as an instrument of control over public moods – both inside and outside one’s own nation – has been known since antiquity. Propaganda is not necessarily deception, and not even always false. It has a different mission: to affect the target audience in order to make it change its opinion about something. Advertising, a commercial form of propaganda, is constantly making us discover new desires, and satisfy them by purchasing the products it offers. Political propaganda makes us vote for certain candidates or parties. International propaganda sways our opinions about other countries and nations, or their governments’ policies.

The basic difference between propaganda and other types of fake news is that it is 100% deliberate media practice. Even disinformation could be sincere: The person transmitting it may actually believe the lie and be completely genuine when distributing it. Manipulations of context can – sometimes – be an outcome of genuine misconceptions; for example, proponents of von Mises’s ideas promote “the gold standard” not because they want to bankrupt their audiences, but because, perhaps, that is what their calculations are telling them might just work. However, both are in reality constantly engaged in propagating their views, fully aware that they are deliberately trying to change their readers’ attitudes towards what they see as objective reality. Part of the audience finds in those messages something it wants to believe and follow. If that group becomes statistically significant, reality itself changes too.

Communications science has been dealing with propaganda for almost 100 years – since the First World War, when mass media became an effective component of military action for the first time. It is interesting that the propagandists acted first, and only later tried to understand what they had done with public consciousness. The core research in this field was done by the same people who were actively “littering” the brains of their own people, as well as their enemies, in 1914-1918. Walter Lippmann, the founding father of journalism as a science, worked in the Committee on Public Information, a Wilson administration propagandist institution that was responsible for “selling” the war in Europe to Americans. His fellow committee member Edward Bernays created the theory of public relations (along with propaganda). Lord Arthur Ponsonby, a key British researcher of propaganda methods and techniques and the author of the fundamental work Falsehood in War-Time (1928), was not involved in propaganda directly, but observed the actions of the British mass media and the government from a close vantage point: Parliament.

The methods and tools of propaganda were an important (if not the most important) instrument of Communist parties in Russia and Central and Eastern Europe, especially the Bolsheviks and their successors in the Soviet Union. They grasped the ability of mass information to change public opinion and collective consciousness earlier than the fascists did. Similar to other totalitarian regimes, communist Russia made propaganda a tool to control society, an indoctrination machine. Ideas and means conceived during the two world wars have produced ways to manipulate peaceful societies; with frightening inevitability, such societies have turned into militaristic “zombies”, ready to follow the orders of the Fuhrer or the Politburo and join the “class struggle” or a “race war.”

The propagandistic Axis powers who were defeated in 1945 provided Western researchers plenty of material to study the use of propaganda as a weapon. During the Cold War, which started soon thereafter, the techniques used by the Nazis and their former allies, the Communists, were blended together. In 1950-1980s, Frankfurt School philosophers and sociologists in Germany (Hannah Arendt and Jürgen Habermas), French Structuralists and Post-structuralists (Ronald Barthes, Jacques Ellul, Louis Althusser, Jean Baudrillard, Régis Debray) and Italian philosopher Giorgio Agamben managed to explain the nature of aggressive propaganda and the techniques that make it efficient. At the same time, constructivist philosophers, Karl Popper and Karl Jaspers in particular, were actively working on “vaccinating” European democracies against the totalitarian virus, including by use of the most dangerous medium of all – television.

When the communist system fell in Europe in 1989-1991, it looked as though the liberals’ ideal peace had finally arrived, in which there was no systemic opponent – no totalitarian egalitarian ideology based on propaganda and deception. It seemed that the propaganda era was over: The former enemy, socialist countries including Russia, started avidly absorbing Western communication methods, developing an aversion to censorship and ideology. However, propaganda is not exclusively a weapon of totalitarian regimes. It is practiced, albeit subject to many limitations and clauses, by all countries, even the most democratic.

As was already mentioned, propaganda is the deliberate manipulation of information in order to influence society’s behaviour. Coming back to [political] life to become a tool of real politics is also a manipulation; it just aims at the narrow social group known as “political leaders”. One way or another, propaganda lived through the lean years of the “noughties”, to rise like a phoenix from the ashes in the world of the Internet and social media.

The Russians did it

After November 8, 2016, when Donald Trump was elected president of the United States, the power of information manipulation (propaganda) started being discussed not merely with excitement, but in a frenzy. Memoirs about active measures by Russian intelligence (for example, a story fake about the origins of AIDS) were dug up from the dusty annals of Cold War history, and “Operation Trump” was promptly equated with “Operation Infection”. Russian spies, real and invented, flooded Washington; an army of trolls led by the evil Putin attacked the pristine consciousness of American racists from the Southern states and paved the way for Trump’s victory.

Once again, propaganda as a tool became the centre of attention – this time, significantly amplified by the problem of little understood and lightly controlled social media, primarily Facebook and Twitter.

Even considering its level of aggression, and even in a situation of unlimited digital distribution, propaganda follows the rules and patterns of media influence identified by scientists. Although people are ready to be deceived, to achieve a discernible effect – not to mention a decisive one – messages should be frequent, and the information should be socially relevant. The Agenda-setting theory (McCombs et al, 1994) provided quantitative proof that for a politically significant effect, the audience must be subjected to long-term and frequent exposure. The cultivation theory, which describes the impact on the audience of messages indirectly encoded into popular TV shows, also yields no examples of a sudden, immediate effect on the audience. Information priming – a harsh manipulative mechanism, partially resembling a provocative interrogation – demands (as we can see from the example of Russian viewers) a monopoly on information and the absence of alternative information channels, but, according to research, the priming effect disappears very quickly when the structure or tone of communication changes.

Although the hypothesis of a Russian influence campaign that could alter an election outcome in the US sounds appealing, it comes up short when tested using the main theoretical tools, and, frankly, simple common sense. To some extent, Russian agents (only a minority of whom were real secret agents) undoubtedly attempted to use “information weapons” to “interfere” in the 2016 US election process, as well as the French and German elections in 2017. Identification and objectification of this “weapon” have already been completed, and, although it may take a while, an antidote will be developed. The problem of fake news in 2016-2017 is just another wave of the crisis of trust in mass media and authorities, which are similar in nature and happen whenever several criteria are met: polarisation of domestic and foreign policies, a technological leap in the field of media communications and a slow reaction to change by social mechanisms.

Internal polarisation is especially noticeable in countries like the USA (where two political forces are continuously changing places), but other regimes are also prone to it to some extent. Society splits on the basis of attitudes toward the existing status quo: one group finds the current state of affairs agreeable and wants slow, natural changes, while the rest are dissatisfied and insist on the need for quick, radical action. Populist leaders (including Trump, and even Putin) are capable of fuelling such polarisation, but even their malevolent intentions are not omnipotent: History shows that social, economic and military crises are radically reducing polarisation and helping societies become immune to this disease.

External polarisation, meanwhile, is a more of a made-up effect than a reality. The modern world is not divided into ideological alliances; unions are pragmatic. The myth of the external polarisation of the world is used in domestic policies as a bogeyman, or a symbol of a threat.

A technological leap in media communications has been going on for 20 years already; during this time practically all aspects of the information and entertainment businesses have undergone changes, with the emergence not only of new media technologies (the Internet, mobile devices, social networks) and new forms of distribution (from Netflix to push notifications), but also of radically new forms of media organisation. This constant wave of innovation is destroying the “old media” and creating “new media”, which it quickly renders outdated. Technological challenges often simply fail to emerge; progress rushes past, paying no attention to the problems and “time bombs” it leaves on the way. Certainly, the exciting anonymity and total freedom of Internet communications, romantically built nearly into the very design of TCP/IP protocols, is today reaping the whirlwind of botnets and cyber accounts, engaged in less than pleasant activities. Universal access to programming tools and relatively open access to the codes of key systems create many possibilities for hackers. People’s dependence on computer control systems increases the threat of cyber-terrorism.

The slow (delayed) social response to today’s challenges is an important component of our crisis. The welfare states built in the second half of the 20th century put some unsolved (or unsolvable) social conflicts under a long-term anaesthetic. Global economic growth, which continued even despite the crises of 1998-2000 and 2007-2009, was an additional “painkiller” – despite the stagnation of the middle class in most developed countries, and the growth of inequality, on the whole, societies are “satisfied” with the performance of their governments. However, the extended anaesthesia does not change the fact that Western societies (and Russia’s as well, by the way) are riven by contradictions. As the most numerous generation (the baby boomers) began ageing and their retirement years grew longer (due to growing life expectancy), it turned out that many 60- or 70-year-olds were ready to tolerate the pain of social frustrations only when they were kept busy. This effect was particularly noticeable during the 2016 US election campaign; Trump is the president of disgruntled baby-boomers, while Barack Obama, a representative of the next generation, not only failed to decrease the level of discontent in society, but on the contrary, he heated it up.

The slow social response is like an overheated kettle, capable of whistling as it releases steam, but chaos, panic of the elites and many errors can easily appear in this process.

To the objective reasons behind the fake news crisis, we obviously also need to add the subjective. There are many different interests in the modern world – state, private, corporate, institutional. To achieve their goals, some representatives of these interests could (and, as we know, actually did) use natural problems. Plunging Russian audiences into the muck of scandal helps the Kremlin stay in power. Donald Trump became president thanks to his effective exploitation of the problems of public trust in the US. The European right-wing – such as the Alternative for Germany and Italian radicals – gained parliamentary strength. Vladimir Putin, engrossed in 3D geo-political chess, is promoting illusory Russian “national interests”.

The main threats of the fake news crisis are definitely linked to the structures of trust. Societies, as well as the international community, will sooner or later create new, more advanced and more stable structures. They will not necessarily need to be similar to media institutions familiar to us (press, television, journalism as such) or traditional diplomacy.