Putin’s address to the Federal Assembly heralded major changes in Russia just as life was getting back to normal after New Year’s Eve. The president announced his decision to strengthen presidential powers, expand support for young families with children, increase funding for teachers and primary healthcare and reform the healthcare system and macroeconomic policy.

Political decisions have already assumed the form of draft constitutional amendments; the range of social and humanitarian improvements is much more modest. Looking closely at the changes in personnel, the appointment of Mikhail Mishustin as prime minister speaks in favour of the Kremlin’s technocratic approach to governance. Hence, one of the new government’s innovations might be a focus on evidence-based policymaking (EBPM), i.e. public decision-making based on research and scientific findings. EBPM became popular in the West 20 years ago. However, its outcomes are ambiguous.

What is evidence-based policy?

In September 1999, the iconic American political television series The West Wing presented an ideal expert politician, President Josiah Bartlet. In the series, governed by his intellect and high moral standards, Bartlet, the Nobel laureate in economics, steers his Democratic administration towards solving many internal, national and international problems. An ideal expert politician like Bartlet uses scientific knowledge and convincing arguments to achieve the common good. It is quite rare to come across replicas of President Bartlet in everyday life.

On average, politicians with an academic background who manage to reach a leadership position are no more successful than their less educated colleagues. At the same time, demand for scientific advisors from various advisory councils, think tanks and universities has never been greater. The efficient work of scientific advisors differs from the way Bartlet’s fictitious administration operated. Evidence-based policymaking entails the availability to politicians of applied research, as well as the adjustment of advanced decision-making to local conditions. Thus, in the real world, scientists have an auxiliary role rather than a seat in the government.

But what is evidence-based policy in the context of public administration? It emerged in medicine after World War II, when new discoveries were no longer delivering large-scale therapeutic effects comparable to the discovery of penicillin in treating infections, or insulin for diabetes. Effective new developments could no longer come from simple monitoring of patients’ health condition before and after medicine administration. Readers can themselves feel the effect of antibiotics on an infectious disease (such as a sore throat) but will not see the difference between the effect of penicillin and tetracycline without an extra medical examination. Thus, evidence-based medicine became essential to improving public health.

A similar process is afoot in the social sciences, especially after the fall of the Berlin Wall, which symbolised the triumph of capitalism, democracy and liberalism. This triad is present in contemporary developed societies. Problem-solving requires advanced research which only scientists can offer.

That said, evidence-based policy making has no universal definition. Some members of the scientific community tend to believe it’s a sustainable policy aimed at the development and endorsement of government decisions based on empirical evidence collected and analysed using scientific methods. Other researchers draw attention to the natural subjectivity of evidence-based policy. Scientific research, along with more traditional arguments (opinion polls, financial data or evaluation of previous policies), simply bolsters support for particular policy solutions. In other words, policymaking is a kind of bazaar where sellers (politicians) offer products (policy decisions) by presenting their evidence-based effectiveness.

Thus, evidence-based policymaking depends on the quality of two factors. First of all, evidence can be of top quality or the quality of a failed coursework paper. Second, policymaking can be open to substantiated discussions and evidence, or can resemble evening TV political shows, full of fights and false arguments. So the properties of evidence and policymaking interact with each other like the ingredients in a cocktail, which can lead to a pleasant evening, or a headache.

Evidence-based policy in contemporary states is based on several scientific developments. The first is experimental research, the gold standard in social sciences. For example, back in the 1970s, the effectiveness of American social programmes was tested using large-scale experiments. The results of these experiments helped change the welfare system. These experiments became more sophisticated over time. They were extended to other areas of regulation— like education, poverty relief, and international aid.

Second, evidence-based policy is often based on statistical data collected by governmental agencies. These data contain tens of thousands of observations. Each have their use in scientific analysis. This helps both to identify policy deficiencies and to draw a detailed picture of the public sector. Research by the Saint Petersburg Institute for the Rule of Law is one of the most striking examples of the use of such data in Russia. Using statistics from law enforcement agencies, the institute determined that when police seize drugs, the amounts only slightly exceed the thresholds for higher sentences (a substantial amount, punishable by 0−3 years of imprisonment, or a large one, punishable by 3−10 years). This case shows that official data may unintentionally reveal problems with governance, especially when they have to do with sensitive issues or a marginalised group lacking political representation (e.g. drug users).

Finally, evidence-based policy is open to new scientific and technological developments. Big data, artificial intelligence and behavioural economics offer new opportunities for solving social problems. Big data is used in border management (identification of suspicious persons), by police (face recognition and crime location prediction) and tax authorities. Evidence-based policy helps to combine new scientific and technological developments with state decision-making.

Yet, evidence-based policy cannot solve all social problems. First of all, the evidence itself may be flawed. The quality of research relies on honest and proper application of scientific principles of analysis. These are not always guaranteed and verified. Second, politicians can use a piece of evidence in their own interest. They are prone to ignore conflicting findings. For instance, Putin’s pension reform was an evidence-informed decision to raise the retirement age. But alternative measures were available to get resources for the payment of pensions. These include the adoption of best practices to fight corruption, cuts in spending on security agencies and optimisation of the bureaucratic apparatus. In other words, in the case of evidence-based policymaking, it is up to the official to make a decision. No studies will offer indisputable solutions to social problems.

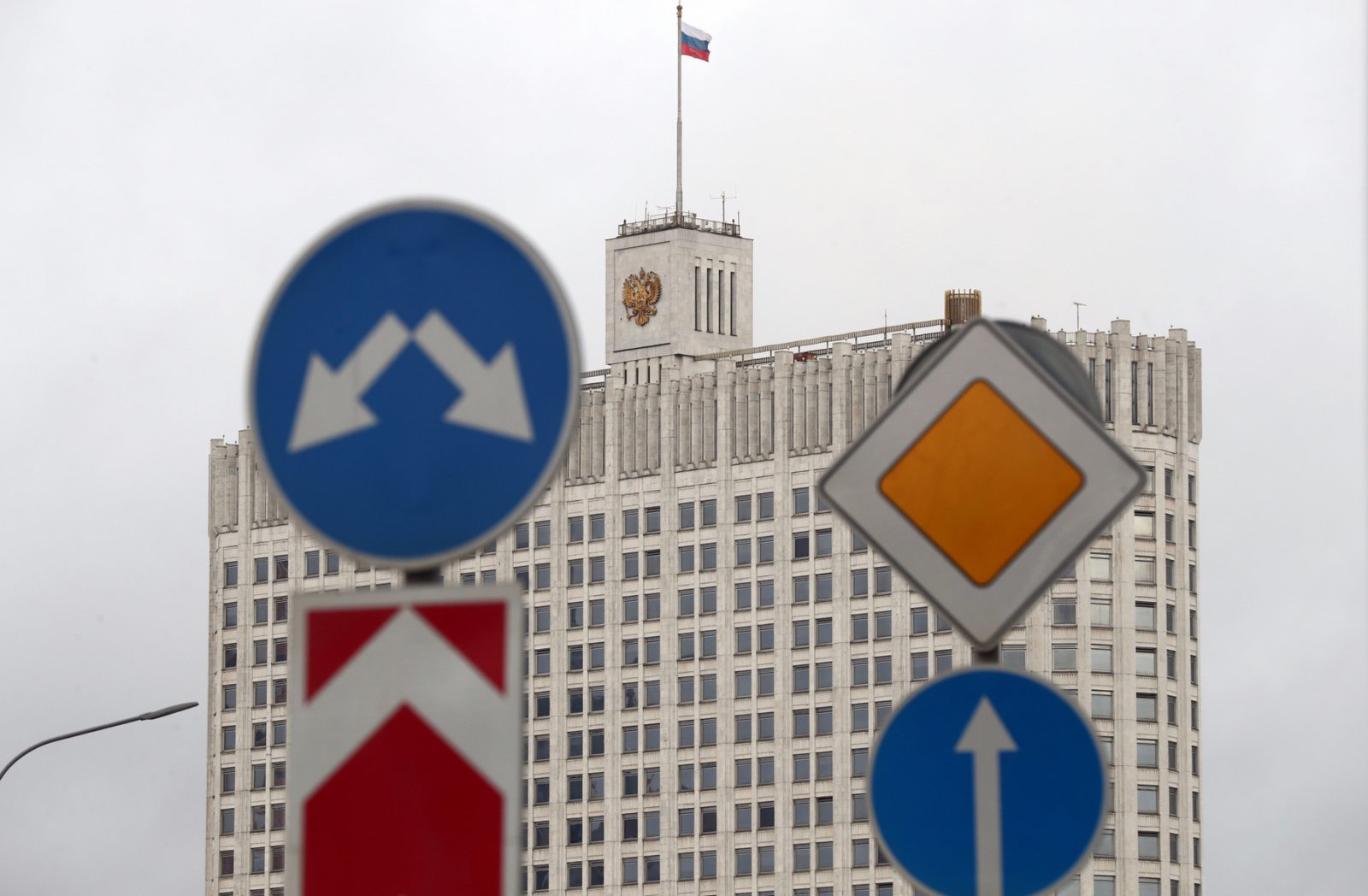

Evidence-based policymaking in Russia

The prospects for evidence-based policy in Russia are not obvious. Vladimir Gel’man doubts that improvements in governance in Russia are possible without changes in the political system. The system favours politicians who focus not on social and economic developments, but on ensuring that Vladimir Putin and United Russia stay in power. Moreover, the super-centralisation of power in Russia can simplify overly-selective collection of evidence by subsidising privileged think-tanks and streamlining policies by suppressing dissenting opinions.

The Central Bank of Russia and Ministry of Finance are a perfect exemple of this. These are some of the most efficient Russian state agencies. They have repeatedly been recognised internationally since 2007 for their monetary-policy and fiscal-policy results, which helped stabilise the national economy and reduce crisis-related damage. The CBR is one of the most independent agencies in the country. The Kremlin can take away its independence at any time. But it does not do so for the sake of macroeconomic stability. The Kremlin appreciates technocratic fiscal and monetary policies that ensure the predictability of the Russian economy without changing its fundamental properties.

More complex areas of public policies pose more problems. For example, the failed police reform was unprecedentedly public. Many experts got involved and there were public consultations. Ultimately, the majority of independent expert opinions were rejected or dismissed in practice; the process of reform fell to the Interior Ministry. Serdyukov’s armed forces reform, developed with the participation of experts, was only partially implemented. Mainly the reforms were to improve technical facilities and strike capabilities. As a side effect, the officer corps was reshuffled. Military hazing and problems with the military education system remain unchanged, while the armed forces lie further beyond public oversight.

Thus the political part of Russian evidence-based policy will come against restrictions caused by the Kremlin’s policy bias. Prioritised areas may reach a higher technocratic efficiency level backed by scientific evidence. Yet social, humanitarian and political changes will be checked against their potential for preservation of power by the incumbent elite — no matter what the experts say.

Apart from issues of politicisation, the quality of evidence can also be questioned. First, the quality of higher education in social science and humanities is quite low. Recently, the Russian Academy of Sciences recommended to retract more than 800 ‘scientific’ papers for unethical publication practices. Anti-plagiarism software identified more than 70,000 papers by Russian authors published two or more times.

Second, political censorship in academia has intensified. The management of the leading universities is appointed by the government or president, while lecturers and students are punished for political and civic activity. The symbolic atmosphere of intensified control is rapidly spreading across the academic world. Statements and research in social sciences and humanities are self-censored. For example, the leading Russian think-tanks working on foreign policy issues never criticise strategic foreign policy initiatives. They provide only viewpoints supportive of official policy.

Finally, public advisory services serve a dual purpose, which turns any independent analysis into a digested content acceptable for the federal and regional authorities. Political advice formulated by spin doctors and political strategists is openly aimed at retaining power by the incumbent ruling elite and is passed on directly to the presidential administration. Socio-economic proposals to improve citizens’ lives undergo a multi-layer check against the stability for the Kremlin regime. For example, a so called ‘independent’ evaluation of the quality of services provided by public organisations is in fact biased. The analytical methods and structures are set by public organisations. Thus, experts perform only a technical role of data collection and writing reports.

The confession is the queen of evidence. This well-known phrase in Russia acquires a new meaning in the context of evidence-based policy. Confessions, i.e. acknowledgements of existing political rules by scientists, are a necessary precondition for doing evidence-based policymaking. In turn, public officials acknowledge the contribution of authorised think-tanks.

Evidence-based policymaking will not become the Kremlin’s magic wand. Figuratively, Russia first needs to take a repulsive penicillin pill to invent new modifications of the state. For example, the research by the Institute for the Rule of Law remained on paper and was not reflected in anti-drug policy in Russia. And this is not up to researchers, but officials and Duma deputies incapable of independent decision-making. However, in the technocratic fields of monetary and fiscal policy, which enjoy relative autonomy, as well as in the area of strategic foreign policy, one can expect an increase in the Kremlin’s effectiveness.

Evidence-based policymaking is a new version of an old car model, with upgraded air conditioning and integrated navigation systems. Still, it requires quality fuel, a stable battery and a skilled driver to smoothly move it in the right direction.