Russia’s political parties may receive funds from several sources. Firstly, there are dues paid by signed-up party members. Then there are also voluntary donations from entities or individuals. Alternatively, a party can always turn a profit from its own economic activities. It could even resort to taking out a loan. But all of the above form a minuscule share of political parties’ incomes in Russia today. For example, in 2017 (the last year for which parties’ financial statements have been published, A Just Russia received not a single ruble in membership fees. That same year, donations barely exceeded 0.3% of all revenue of the Liberal Democratic Party of Russia (LPDR.)

This is presumably because the main source of income for parties with parliamentary representation is the Russian state budget. Official state funding averaged about 80% of their yearly revenues for 2017. Between 2012 and 2017, the federal budget allocated about 30 billion rubles to support political parties.

Legally speaking, this is all above board. According to a Russian law entitled “On Political Parties,” political parties that receive more than 3% of the vote in elections for the State Duma are eligible for annual funding from the state. Furthermore, one-time payments are allocated to parties whose candidate receives over 3% of the vote in presidential elections.

A Good Deal?

Russia is not alone in this. Many other states provide various forms of funding to political parties. Supporters say that such state funding allows political parties to perform their functions (promoting their political standpoint, fostering political education, and participating in elections) without making themselves dependent on major donors.

In Russia’s case supporters add that ordinary citizens are not prepared to donate funds to political parties, for cultural and historical reasons as well as the high level of poverty in the country. They are not wrong; Russians are in no hurry to open their wallets in support of political parties. This dependency on state funds appears to be a problem for political parties; in contrast, other public organisations have learnt to survive on donations made by ordinary citizens.

For example, in 2017 the charitable foundation “Help Needed” (Nuzhna Pomoshch) received 166 million rules in donation; almost 50 times more than all donations received by the LPDR, to which citizens and legal entities donated just 3.5 million rubles. The Communist Party of Russia (KPRF) and A Just Russia also received less in donations than Russian charities: 63.4 million and 152.2 million rubles respectively. Only the ruling party United Russia received more charitable donations than state financial support; the bulk of these donations were made by large corporate donors often associated with the party’s members and employees. Nevertheless, when it came to donations from individuals, United Russia received two times less than the “Help Needed”.

Peak Party Performance

Today it is obvious that political parties, which should be representing the interests of Russian citizens, are fighting a losing battle when it comes to attracting voluntary donations. The reason is not only that citizens are generally not prepared to donate some of their modest earnings to others; it is also because ordinary Russians see no reason to share money with political parties in particular.

According to recent data from the Levada Center, Russia’s political parties now have a negative confidence rating. This means that citizens tend to distrust rather than trust them. As a result, political parties now compete for last place among trusted public institutions, alongside big businesses.

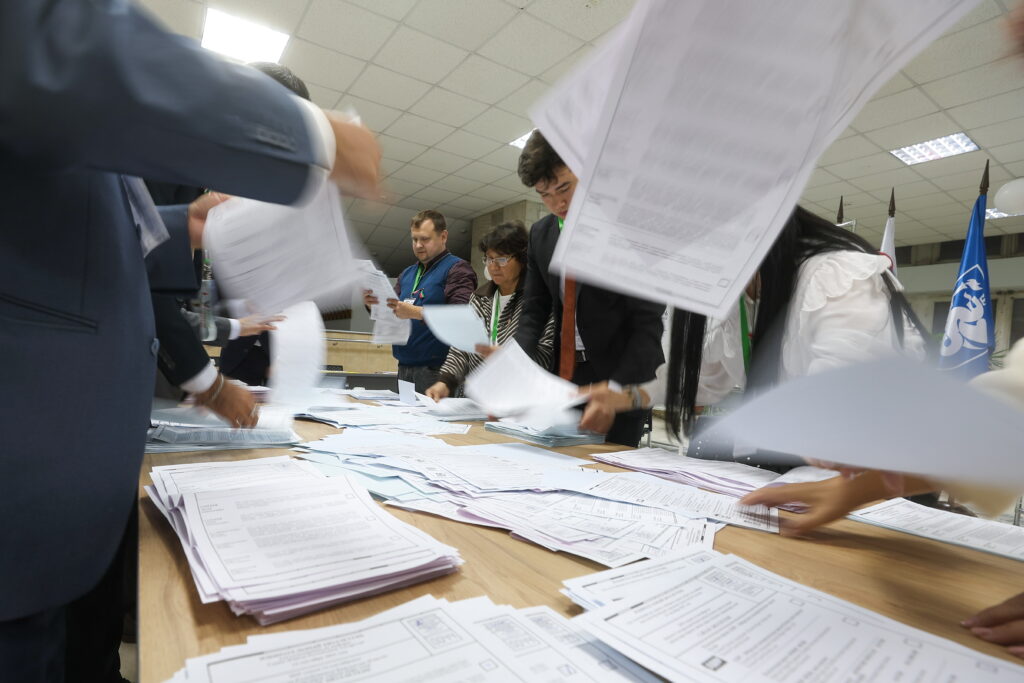

Of course, it could be said that raising funds for charity and social causes is a much easier task than raising money for political activities. This is to a degree the result of insufficient political education, which parties must learn to overcome. They could also become more active in elections; these parliamentary parties seldom go to the polls. Last year’s study by Golos, an NGO for the protection of voters’ rights, demonstrated that, apart from United Russia, political parties barely participated in local government elections at all (which should, as a rule, provide an opportunity for citizens to make themselves heard on pressing social issues.) For example, the KPRF ran candidates in only 13.6% of elections for municipal heads in only 16.9% of elections for local deputies. A Just Russia ran candidates in just 5.7% and 14% of these elections respectively.

Election related expenses make up only a small share of parties’ budgets. The only exception is the LDPR, which allocated three quarters of all its resources over the past six years to election campaigns and propaganda. For other parties, these costs are much lower, averaging about 30% of all funds in 2017. 53.2% of all United Russia’s expenses for 2017 went on party upkeep (“maintenance of regional offices” and “maintenance of governing bodies”), while 49.8% of all the KPRF’s expenses and 35% of A Just Russia’s went towards the same. In contrast, just 6.6% of LDPR expenses that year went towards party operations and management. Meanwhile, that same year, Need Help’s administrative expenses amounted to only 3.9% of the foundation’s budget.

The effectiveness of these parties, which survive almost entirely at the expense of taxpayers, can be easily measured by way of those same taxpayers’ votes: ordinary Russians’ support for these parties is manifestly decreasing. While 64.6 million valid ballots were cast at the State Duma elections of 2011, by 2016 this figure had dropped to 51.6 million. This despite the fact that, over the same period, the number of parties participating in the elections doubled.

By the logic of the law “On political parties,” which set out the parameters of state funding for political parties, a decrease in electoral support should have led to a decrease in financial support accordingly. After all, the amount of financial support a party receives is calculated based on the number of votes it received during an election; in a sense, each voter is “worth” a certain sum. Yet this did not happen; immediately following the 2016 elections, State Duma deputies amended the law and increased the amount of financial support it offered. Consequently, the ratio of state financial support to each vote received by a political party increased 30.4 times between 2007 and 2018. According to Rosstat, the Russian State Statistical Agency, the average salary in Russia increased just 3.2 times over the same period.

It has now become established practice for political parties to resolve their financial difficulties at the expense of taxpayers. One illustrative example was a loan of 600 million rubles which United Russia took out in 2007, a year of elections to the State Duma. The following year, deputies of the State Duma (about 70% of whom represent United Russia) increased the amount of state funding available to political parties per vote by four times. Accordingly, United Russia’s annual financial support from the state grew by precisely 600 million rubles, which went towards repaying its loan.

Who Earns from Party Business?

All of the above is now established practice. It is a practice which shows that political parties have become accustomed to resolving their political problems at the expense of taxpayers, but without asking them. Thus political parties transform into bureaucratic structures which move further and further away from their own voters. The need to draw public attention to these problems is becoming more urgent, particularly given that improving the financial transparency of parties and electoral funds is a prerequisite for fighting shadow lobbyism and corruption.

Russian civil society is gradually becoming aware of the problem, as indicated by the appearance of a new project, The Parties’ Wallets, which comprises a database of all known sponsors and contractors working for political parties and candidates for elections. This resource proved invaluable in conducting a study on how political parties spend their finances.

This study indicated that a significant part of political parties’ funds are transferred to legal entities that are closely tied to figures in party leaderships. For example, one of the biggest recipients of funds from the LDPR is the Institute for World Civilisations (IMC), an organisation not simply founded by the party, but by its long-time leader Vladimir Zhirinovsky himself. Between 2013 and 2018, the party transferred 127.5 million rubles to the institute. In effect, this means that the IMC is receiving funds from the federal budget both directly and indirectly. Despite the fact that the IMC is technically an NGO, this is the second year running when it has received a subsidy from the federal budget. It merits its own line in the budget document: in 2018 the institute received approximately 50 million rubles, while for 2019 the state has already pledged a further 120 million rubles.

Other parties have similar schemes. In 2017, A Just Russia donated 108 million rubles for “charitable activities.” The recipient of these funds was not just any NGO, but instead the Centre for the Protection of Citizens’ Rights, which is closely associated with the party. Since 2012, the Just World Institute, which also happens to be affiliated to the party, has received 76.3 million rubles. It should be noted that in 2018, the leader of A Just Russia was compelled to publicly complain about the party’s lack of funds and therefore its inability to pay salaries to party employees.

What is to be done?

In its current format, the system of state financing for Russia’s political parties appears to be fundamentally flawed. Furthermore, it directly provokes a conflict of interest among parliamentarians, who are able to establish the amount of state funding to political parties which they themselves represent.

An alternative to such a scheme in future could be selective taxes, when citizens themselves decide where they want their financial contributions to end up. They could decide whether they want part of their personal income tax or any other tax revenue to support a particular political party, NGO, or religious organisation. Initiatives like this are already in place across the post-Soviet space. Making them work for the good of society will require legislative changes, reforms to the tax system, and above all a willingness to engage from ordinary citizens and politicians alike.