Militaries are often said to be microcosms of society. As Russian military casualties from the invasion of Ukraine mount, it is becoming clearer how inequalities within Russian society at large are reflected on the battlefield. Despite Russia’s reluctance to publish information on its losses, available data show that ethnic minorities from poorer regions are disproportionately prominent among the reported casualties.

Whilst experts have already debated the possibility of Moscow-based elites challenging Putin’s rule, there has been less discussion on the possible long-term consequences of the war in Russia’s regions. My analysis found that the proportion of non-ethnic Russians is the most powerful factor — more so than regional wealth — in accounting for regional casualty numbers. This finding helps account for why we see high deaths reported both from Buddhist regions of Siberia such as Buryatia, as well as Orthodox and Muslim regions in the North Caucasus such as North Ossetia and Dagestan, respectively.

Coupled with the Kremlin’s increasing rhetorical turn towards empire and ethnic Russian nationalism, this threatens to upset an already delicate status quo as authorities in Russia’s ethnic republics seek to balance sustaining support for the war with remaining responsive to their populations.

Ethnic minorities prominent among war casualties

In the days after the February 24 invasion, several videos featuring Buryat POWs began to surface on social media. Later — before Russia’s Ministry of Defense had even officially confirmed the first casualties — several regional governors announced the deaths of their compatriots. Anecdotal evidence mounted that many of the soldiers sent to fight for the so-called «Russian World» belonged to ethnic minority groups from economically depressed regions, with Bellingcat’s Cristo Grozev one of the first analysts to suggest a disproportion of casualties were «non-Slavic» troops from «far-off regions.»

Until recently such speculation remained mostly anecdotal and based upon extremely limited information. On April 6, the BBC’s Russian service managed to compile a list of names and regions of 1083 of the 1351 officially confirmed military deaths using official state and regional media sources. While this figure is dwarfed by the almost 20,000 fatalities claimed by the Ukrainian side, it still provides an unprecedented glimpse into the socioeconomic makeup of the Russian forces.

Perhaps most striking of all? There was not a single officially reported death from Moscow, a city of at least 13 million people, while 93 deaths come from Dagestan alone. Buryatia has the next largest number of fatalities, at 52.

Economics of ethnicity?

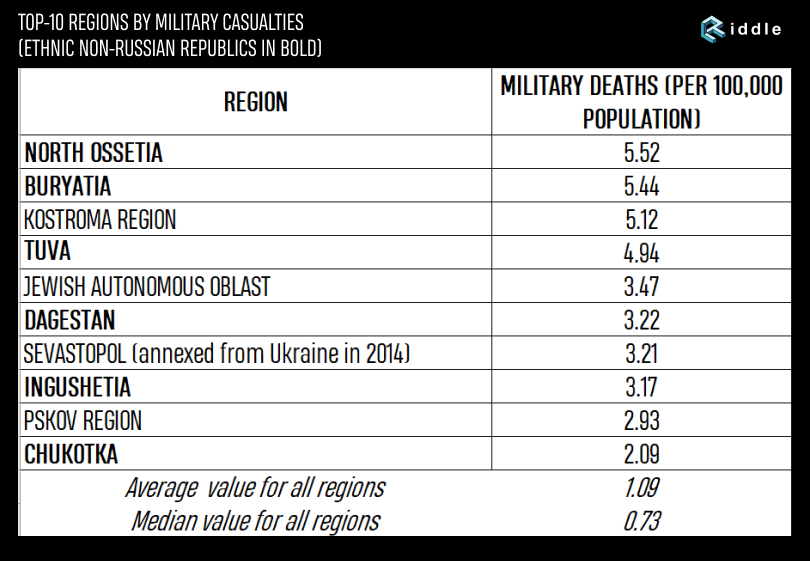

What explains these regional disparities? Several analysts cite how the military tends to attract young men from economically depressed regions — those who struggle to find work or are unable to get out of compulsory military service. On the other hand, casualties do appear to specifically affect minority communities: 5 of the 10 regions with the highest per capita reported casualties are ethnic republics. The total minority population for these 10 regions combined is 63%, as opposed to around a quarter for Russia overall. To unpack this relationship, I ran a regression model to examine how economic wealth and ethnicity may be independently driving the number of war deaths, using official data on regional population and ethnic self-identification from the 2010 Russian census, GDP per capita from 2018, plus the BBC’s data to come up with the number of regional war deaths per 100,000 population.

Surprisingly, whilst both economic wealth and ethnicity were strong and statistically significant predictors of regional war deaths, the effect of ethnicity is much larger — even when controlling for wealth. This means that for each extra 20% of ethnic Russians in a region, the model predicts the number of deaths per 100,000 people to decrease by 0.26 — the equivalent of around 4 fewer casualties for an average-sized Russian region of around 1.5 million inhabitants.

The effect of wealth is much weaker: for the model to predict a similar decrease, regional GDP per capita would have to increase by 400,000 rubles (around $ 5000) — which is no small feat, equating to hypothetically raising the wealth of Russia’s very poorest regions in the North Caucasus (such as Ingushetia and Chechnya) to the national average.

Explaining greater willingness to disclose ethnic minority deaths

If these trends are representative of Russia’s true military losses, this would be strong evidence supporting the argument that ethnic minorities are systematically dying at higher rates than ethnic Russians — a cruel irony for a war officially justified in the language of ethnic Russians’ and Russian-speakers’ rights.

Nevertheless, there are reasons to be skeptical here. Data released by official government sources are likely to be selective and incomplete. What’s more, recent proposals by the Ministry of Defense to bypass civilian authorities when distributing payouts to families of the deceased soldiers may add anotherl layer of difficulty onto an already highly restricted information space. The true picture will likely emerge only much later in the future.

But even if such findings are not representative of Russia’s true overall losses, they suggest something perhaps equally significant: officials are more willing to disclose information about ethnic minority deaths than those of ethnic Russians.

This is particularly stark in ordinary Russian regions. Among the deaths confirmed by media in Orenburg region, for instance, just under 40% were from non-Slavic ethnic groups, compared to an overall non-ethnic Russian population of 25%. In Astrakhan region, whilst non-ethnic Russians make up 32% of the population, they comprised 80% of confirmed casualties.

If this is the case, it would be consistent with social science findings on authoritarian regime dynamics. A large body of research has shown that autocrats face strong incentives to conceal damaging information. Anxiety over such information — and its potential to mobilize protesters — helps account for why not a single death from Moscow was announced, whilst large numbers of deaths were announced in rural and ethnic minority areas — the so-called «Third» and «Fourth» Russias as popularized by economist Natalia Zubarevich. Small, rural communities may not only be less of a risk to political stability, but it may be more costly for the authorities to conceal losses in such areas, given the extent of personal networks and the communal nature of burial ceremonies. For ethnic minority communities, a lack of mobilizational potential and strong inter-communal ties are likely even more prevalent.

If this helps explain the predominance of ethnic minority casualties announced in Russian oblasts, then a similar logic may explain the distinct absence of casualties reported by some ethnic republics. Chechnya’s official confirmation of just two servicemen killed is certainly off the mark by some magnitude, though information from other regions in the North Caucasus is also extremely limited. Beyond the North Caucasus, relatively low reported casualties can also be seen in the ethnic republics of the Volga region; Bashkortostan and Tatarstan feature in the top 10 regions for net casualties, though their per capita figures are lower than the average across Russia. In such regions, the authorities can rely on consolidated political networks and extensive control of local media to suppress damaging information. Indeed, reports from both local journalists and the opposition in Chechnya (relying on anonymous sources) suggest local authorities are trying to prevent public burials from taking place in a bid to limit public information about military losses.

This behavior makes sense considering how elites in Russia’s ethnic republics already face strong pressures from the federal center. This pressure amounts to balancing their roles as defenders of ethnic minority rights in their regions and providers of both material (securing strong pro-government votes, suppressing protests) and ideational (loyalty to the regime) support for Moscow, all while preventing rival political networks from rising up.

Both these roles are linked, and both have entered a period of intense uncertainty amid a war with no clear end. Coupled with a foreboding economic outlook for the future, regional elites’ balancing act will come under unprecedented strain: a situation not so dissimilar to that of the Soviet Union in its final years.