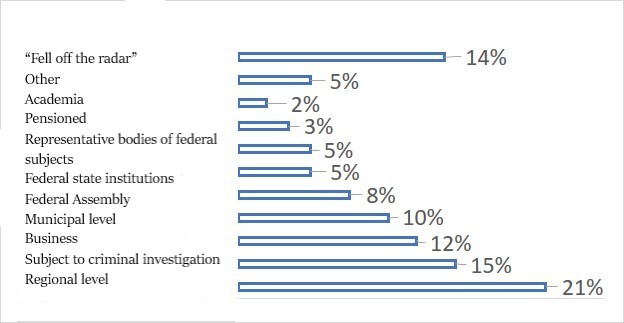

Russian cinema and popular culture are filled with depictions of odious, thieving mayors who, sooner or later, meet a richly deserved fate behind bars. Recall the mayor from Oksimoron’s concept album Gorgorod, or the countless villains on Russia-24’s television series. In real life, however, misbehaving municipal heads do not always get their just desserts. According to a report from the Committee of Civic Initiatives (KGI), from 2008 to 2019, just 15% of former mayors were subjected to criminal prosecution. Furthermore, 21% of former mayors went on to build a career at the regional level, 12% went into business, eight percent ended up in the State Duma, and five percent in federal government. Just 10% continued to work at the level of local municipalities. Does this high indicator of criminal cases against ex-mayors suggest that the job necessarily attracts “bad apples”? Or do the reasons lie elsewhere?

Municipal governance in Russia has a short but nonetheless dramatic history. At the dawn of the 1990s, when regions and the federal centre were bargaining for power, cities were granted the ability to conduct their own local elections. Electing a mayor was a privilege, and certainly not one extended to everywhere at the same time. On the one hand, Dmitry Kozak’s reforms of 2003-2006 completed the establishment of local self-government. On the other hand, Moscow’s moves towards centralisation substantially undermined the financial and political autonomy of local governments, unifying institutional organisation. The transition from elected heads of cities to “city managers” by the end of the 2000s marked the formal loss of political autonomy.

In the spring of 2019, the State Duma started to discuss revising the assessment process for municipal heads’ performance. Alexey Didenko, chairman of the State Duma’s committee on federal political structure and local self-government, repeatedly proposed extend the system of performance indicators currently used to evaluate the work of regional governors to the local level. Accordingly, in 2008 Presidential Decree No. 67, “On evaluating the performance of local government un urban districts and municipal regions,” came into force. It mandated state statistic agency Rosstat to collect information on the condition of small and medium-sized businesses, transport and housing infrastructure, leisure amenities for preschool children, energy consumption, and tax base of local municipalities. The final list initially included 14 indicators, including “popular satisfaction with the activities of local authorities of the city or municipal district by percentage of number of respondents,” and “results of an independent assessment of the quality and conditions for the provision of services by culture, education, social services, health, and other fields by the authorities and other organisations in the territories of the respective municipalities at the expense of budget funds.” It is assumed that this information is being collected behind closed doors. This list of indicators was slightly amended until 2018. However, it has never been used as a legal basis for dismissal of any municipal officials.

Until now, removing a municipal official from office has only been possible with a court order — as a rule, in cases of criminal prosecution such as misuse of state funds. In this light, although dismissal for inefficiency may be a more humane tool when it comes to objectionable local heads, such an approach would radically transform the entire system of political accountability. In his recent address to the Federal Assembly, the president suggested enshrining the principle of a unified system of public governance in the Russian constitution. In practice, experts believe, that would simply mean embedding local government in the national power vertical.

It is worth recalling that the election of mayors and municipal heads was introduced gradually during a process of political bargaining between the regions and the federal centre. At the start of Kozak’s aforementioned reforms in 2003, the overwhelming majority of Russia’s regions had some form of elected government. Kozak’s reform may have systematised the framework regulating the work of local self-governments, but it also laid the foundation for an imbalance between the material resources available to such local governments and the scope of their authority. This culminated in Federal Law No. 131, “On general principles for the organisation of local self-government in the Russian Federation,” which opened up the possibility to appoint a city director or city manager. As a result, since the mid-2000s, many cities have switched to a “two-headed” system of municipal governance in which the mayor remains the head of the municipality, but the city manager is the head of the local administration. This means that the operational management of the city is conducted not by a directly elected municipal head, but by a city manager appointed after an open competition. According to experts from the KGI, between 2008 and 2014, the share of cities overseen by city managers in this manner increased from 26% to 57%. In 2015, the new Federal Law No.8-F34 introduced a new system for electing the head of any municipality, meaning that the representative body of any municipal formation must itself elect the head of the municipality from a list of candidates selected in the course of a competition. By 2019, the share of Russian cities with this “two-headed” model of municipal governance had fallen to 39%.

Besides the “city manager” model, there are formally three further methods of electing the head of a municipality with a population of more than 300 people in Russia today. Firstly, there are direct elections. Secondly, the representative body of the municipality can elect a head itself from among its own ranks. Thirdly, the representative body can elect a head from a list of candidates proposed by a commission overseeing a candidates’ contest. Direct elections for municipal heads have been preserved in only seven regional-level (Novosibirsk, Anadyr, Ulan-Ude, Tomsk, Yakutsk, Abakan, and Khabarovsk), and a handful of district-level administrative centres.

Career trajectories for mayors of major cities in Russia

Source: “Specifics of mayoral rotation in modern Russia”

If we play the devil’s advocate and try to imagine why it is so difficult to guarantee the high quality provision of public amenities at the regional and local levels of government, the following factors are explanation enough. Firstly, there are virtually no funds available on the ground — and that’s not a consequence of poor work or inefficient tax collection. Merely ten percent of Russia’s state entire state budget is allocated to local budgets. The lion’s share of taxes collected locally simply accrues at the federal level and does not find its way back to local communities. Secondly, numerous studies indicate that municipal government, like many other walks of life, is being strangled by excessive state regulation. This means that time and resources which could be directed towards the task at hand are instead spent on legal costs, reporting to superiors, and other risk insurance measures.

From the very outset, the position of municipal head is a vulnerable one which offers few prospects of an enviable political career today. Municipal heads find themselves ensnared by “doubled” political and administrative accountability. On the one hand, elected heads are still accountable to the population at large and are obliged to provide the services and amenities they promised. On the other hand, given municipalities’ near complete material dependence on higher levels of government, it is the governor’s administration, rather than the wishes of local voters, which turns out to be the decisive factor. Nonetheless, local heads are often held responsible for things which, as a matter of fact, are not up to them. In short, their obligations are many, their material resources are few, and they have very limited legal mechanisms available to them to establish effective spending of budgetary funds and attract additional redistribution of those funds. Therefore, local heads’ most effective strategy for survival is not to reform or take initiative, given that any innovations carry the risk of violating formal procedures which can result in administrative or even criminal prosecution. If the local head and his or her team decide to push for any kind of managerial innovation, they do so at their own peril and risk.

Today, this concerns 2,345 high level municipalities, including 1,731 municipal districts and 614 urban districts. In addition, there are approximately 152,125 rural settlements. The quality of management and the level of financial and political autonomy varies widely between municipalities and from region to region. This leads to the question: if everything is so dire, what explains the more or less decently managed towns and cities in Russia today? What determines the quality of provision of goods and services at the local level?

Firstly, this depends on the level of budgetary and administrative autonomy. The municipality most interested in resolving these issues tends to be the one which copes with them most effectively. This is the basis for the principle of subsidiarity: the independent solution of problems under local responsibility. Secondly, the presence of a healthy degree of political competition and a regular rotation (at least on the regional level) of officials plays an important role. The prospect of reelection provides incentives for them to do something tangible and visible in voters’ interests. Thirdly, professional background, communications and managerial skills also matter. Members of business networks or former “siloviki” (who are seldom found at local levels of government) can bring in their own people and new managerial practices. Furthermore, some studies indicate that the method of rising to power — by appointment or through elections — also has a correlation with different attitudes to risk and the quality of local management. Thus appointees tend to avoid taking risks, even those associated with necessary innovations. But in conditions of strong vertical accountability along a political hierarchy, they are better able to cope with the tasks assigned to them, because they do not constantly have to resolve political conflicts as elected officials do. Finally, the strength of local civil society plays a prominent role. Even a non-democratic context such as Russia, various groups and local initiatives are able to exert social pressure and communicate their dissatisfaction with poor local governance to higher echelons. This same dynamic can be observed in municipal governance in China.

These factors for success generally apply to any local government, in any country. Russia is not an exception. However, adjustments must be made for the dominant form of political regime, which in Russia’s case can be termed a consolidated electoral autocracy. It is known that in such circumstances governors are forced to a certain extent to provide the requisite share of votes and increased turnout in federal elections. As municipal heads are de facto accountable to regional administrations for everything from the efficient use of funds, they also have a role to play in these electoral processes. Municipalities in Russia’s political conditions can therefore be considered an extension of the vertical of power. If this is so, then the survival of leaders at the most local level of government may also depend on election results and their success in ensuring the political loyalty of the population.

So how does political mobilisation affect local governance? Does it affect it at all? Two possible answers suggest themselves. The first is that the assistance which municipalities feasibly provide in ensuring turnout, votes, or both results in additional bonuses, access to financing and other programmes which in turn increase the budget available to local heads, giving them more room for manoeuvre. Essentially, political loyalty and budgetary autonomy are mutually reinforcing. The second answer is more pessimistic: if municipalities need to take extra efforts to ensure turnout and votes, they can potentially distract their staff, and divert their resources, away from solving pressing problems, thereby distorting the system of managerial priorities.

The standard Russian municipality gets its revenue from higher-level budgets (subsidies, grants, grants-in-aid, and so on), as well as from their own earned income. The municipality cannot spend the first category of budget funds at its own discretion since, as a rule, they can initially be spent for a specific purpose (for example, repairing a roof) until the budget year ends. Therefore, the size of the budget is not always necessarily a good indicator of the budgetary autonomy of the municipality in question. Moreover, most revenue from the budget is directly linked to the size of the municipality’s population, meaning that municipalities merely implement the orders of regional authorities. An important source of funds which does allow municipalities to spend funds more flexibility is their own income, together with additional funds raised under various assistance programmes.

One way or another, the quality of the provision of local goods and services depends on budget autonomy and the political pressure exerted on municipalities. This political pressure or responsibility includes the need to provide votes and turnout for the authorities when required. Budget autonomy is a prerequisite for any quality governance, but political pressure complicates the already fraught lives of municipal heads. While it may seem as though their efforts to deliver votes are somehow rewarded by the regional authorities and may even offer bonuses allowing them to improve the local quality of life, this does not appear to be so. In other words, a high level of autonomy and the absence of political pressure are the necessary prerequisites for quality local governance.

This is generally confirmed by preliminary statistical calculations based on Rosstat’s Database of Municipalities (BDMO) and municipal data from the Ministry of Finance. We at the European University at St Petersburg have calculated a quality index for the provision of public goods and services to understand the degree to which it correlates with the municipality’s income level and the percentage of votes its residents cast for the ruling United Russia party during the last Duma elections in 2016. Given that the federal authorities’ general tactic during these elections was to demobilise the electorate of large cities, there will be noteworthy differences between cities and other municipalities.

According to our calculations, the level of quality of public goods and services depends on budgetary autonomy and pressure to deliver votes. While the level of budget autonomy has a more or less positive effect on the quality of these amenities across the board, then the pressure to deliver votes is especially detrimental to quality of municipal management. However, this is not quite as obvious when it comes to local governance in cities. The dynamic of city governance is so different that it can be difficult to identify a single scenario. Relatively successful municipalities are particularly sensitive to this pressure to deliver votes. In rich regions, the quality of governance deteriorates more rapidly with each additional percentage point of votes delivered to United Russia — but there is no such correlation for rich cities. In short, the requirement to deliver votes does not actually result in any additional bonuses for municipalities. On the contrary, this electoral pressure appears to negatively affect the quality of governance in smaller and relatively autonomous municipalities.

In conclusion, it is fair to say that even under an authoritarian regime, enclaves of good governance on the local level can arise. However, they do not face any prospects for sustainable development given their lack of budgetary and political autonomy and their regulatory constraints. Non-urban municipalities with a bearable financial situation are particularly affected by excessive political pressure. As a rule, cities are richer and their political landscape is more complex, meaning that the effects of this political pressure are harder to establish. Finally, the “political machinery” and mobilisation of voters functions more smoothly in rural areas and settlements with large industrial concerns. Russia’s municipal governments remain poorly understood, at least in comparison to regional governments — there is much that we still do not fully understand about the processes on the ground given the lack of reliable statistics. However, the growth of opposition activity during Moscow’s local elections last year and the opposition’s “smart vote” drive have slightly increased interest in municipal political processes. It remains to be seen whether it will lead to a broader political shift.