Many of the problems that flared up in Moscow over the summer have smoldered across the country for several years. Barring candidates from running and invalidating signatures from real voters supporting the nomination of an independent politician are time-tested tactics in Russian elections. Everyone who has taken part in an election at a level higher than their village council over the past 15 years knows that registering as a candidate by collecting signatures is practically impossible, unless the candidate is approved by the administration. This is the case regardless of the number of signatures that need to be collected. In the Irkutsk City Duma elections this year, several candidates were declined to be registered, even though only 65-70 signatures needed to be collected, not 5000-6000 like in Moscow. The same justifications were used to invalidate candidates: certificates issued by the internal migration service and handwriting experts.

The more serious the imminent election, the less likely that collected signatures will be recognized as valid and reliable. That is why “parliamentary privileges” are such an advantage, as they allow some parties to nominate candidates for the State Duma without having to go through the signature collection process.

Meanwhile, there were no major changes in the control of power over the media. Research conducted by the Golos Movement for the Protection of Voters’ Rights showed that even before the election campaign started, local newspapers aggressively promoted candidates from the “City Hall list”. These special editions cost taxpayers about 200 million rubles. Essentially, the city was subjected to censorship funded by its own citizens.

Adding to the fact that opposition candidates were denied access to local media, they faced obstructions when canvassing too: they were attacked, beaten, had feces thrown at them, and sometimes their campaign stands were simply confiscated by police. As a result, the already difficult task of conveying their position to voters was stymied in several ways.

And at the last stage of the election campaign – just before election day –the traditional pressure operation on voters controlled by City Hall began.

The three pillars characterizing all elections in Russia were present: control over candidate registration, over the information sphere, and the utilization of the dependent electorate. It worked this way in Moscow until this summer.

So what changed?

From mass media to the masses’ media

Real elections cannot be held without the ability to engage in meaningful public discourse. If political discourse does not exist, elections turn into an unconscious voting reflex (as was the case in the March 2018 presidential elections). In this scenario, a real expression of will cannot be said to exist.

One guarantee of public discourse is freedom of expression, including the ability to assemble peacefully and nonviolently. It was the street protests of this summer that undermined the mayor’s media monopoly and violated the campaign script written by City Hall.

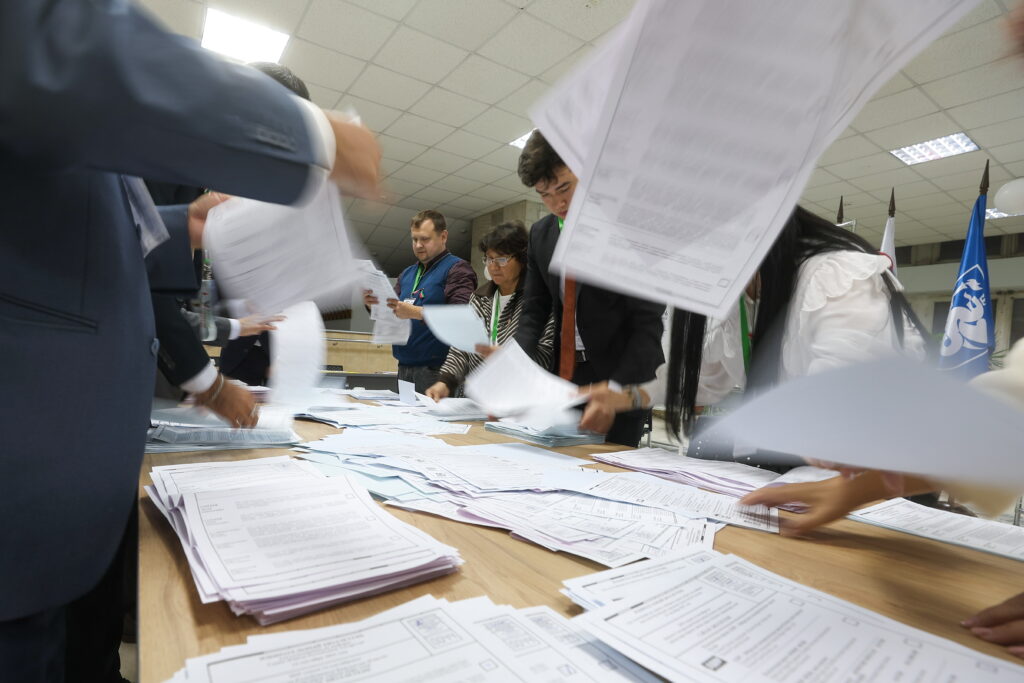

The rallies calling for the registration of opposition candidates provoked a completely unhealthy reaction from the siloviki, who were only starting to recoup from their extremely disappointing defeat in the Ivan Golunov affair. In fact, the siloviki had played a major role in the previous election campaign. Their involvement was noticeable at every stage: law enforcement officials invalidated signatures supporting candidates’ nominations, dispersed street protests, detained opposition leaders, interfered with canvassing, confiscated campaign stands and arrested activists, and in some cases, put obstacles in observers’ way on election day. Compared to the previous year, the number of transgressions by law enforcement officials reported by citizens to the Golos Electoral Fraud Map increased nine-fold.

Politicizing society

Footage of civilians in the capital being beaten and thousands of innocent people being detained, including foreign tourists and even United Russia’s own supporters, changed the story. These mass protests were no longer just about procedural irregularities in the elections, but also about the wider struggle against the arbitrariness and incompetence of people in power. This fundamentally changed Muscovites’ attitude toward the protests, as opinion polls show. Thus, the masses in the streets began to set the agenda in the media sphere, even when most opposition leaders were behind bars.

As a result, political mobilization increased sharply, and in rather consolidated areas, most strikingly in academia, although this was admittedly limited to a few very prestigious universities.

It is telling that Valeria Kasamara, the vice-rector of the Higher School of Economics, became a kind of symbol of these elections, standing as a City Duma candidate while the university leadership reassuringly chanted about HSE’s “political neutrality”. In the background of these claims stood abuses of administrative resources to the vice-rector’s benefit, dismissals of several undesirable political scientists, bans on student talk shows inviting opposition politicians on as guests, student arrests and interference with student events supporting them (at the “Yama” public amphitheater and on HSE Day).

The academic sphere responded by self-organizing: students began to write letters and campaign in support of political prisoners, while their teachers and lecturers simply started studying the electoral documents and justifications for candidates’ invalidation available to them. Heated debates broke out within universities about the boundaries of academics’ political neutrality – professors engaged in bitter arguments in the media and social networks, proving that universities have indeed become politicized.

Shifting perceptions of normality and disoriented conformists

Changes in the political preferences of the Russians over the past year have led to another significant outcome: purely for politically tactical purposes, the “establishment” candidates have started to distance themselves from the party in power. Even some prominent party functionaries took part in the elections as self-nominated candidates, immediately spawning a new buzzword: “samomedvezhentsy” (‘self-bear’, referring to the bear symbol used by United Russia). Nonetheless, the distancing measures were not particularly effective – voters easily identified them as candidates approved by City Hall, just by looking at whose campaign team had the largest presence at the polls, who was getting profiled in local newspapers and whose pictures were plastered on apartment bulletin boards.

Consequently, the conformist vote – favoring the party in power – was demobilized. Conformist behavior and voting bases itself on whatever is most acceptable in a society. But when authority-backed candidates start to hide their affiliation to these authorities in a very conspicuous manner, conformist voters have to ask themselves whether voting for “establishment” candidates who try to publicly distance themselves from power is really all that socially acceptable.

At the same time, members of the systemic opposition have also begun to position themselves much more radically than before. In order to muddy the waters of the consolidating protest vote, they began to use the term “single opposition candidate” in their own campaign messaging. Some even pretended to attack themselves in a promotion film parodying the Russian comedy film “Election Day”. On the actual election day, rumors spread about a bus of LDPR observers being attacked in Tuva, although later, Interior Ministry officials published videos showing that no attack occurred and officially stated that no evidence of a shooting had been found at the scene. During the campaign itself, LDPR candidates themselves reported some less than credible threats (for example, one Moscow single-mandate candidate shared a statement that a beat-up teddy bear covered with red paint was allegedly planted at the door to his apartment with an ominous note saying “Think…”).

The very notion of “normality” in politics has shifted to the more oppositional side – the ruling class has started to hide the fact that it is the ruling class, while the parliamentary opposition is making itself look much more radical.

System error

For decades, the use of an electorate dependent on the government has been one of the most effective tools for the self-preservation of power for the Moscow City Hall. That is how it was during Luzhkov’s time as mayor, and so it remained under Sobyanin. The number of state employees, clients of social security services and other voters included in this ‘clientele network’ remained relatively stable. Therefore, with a low turnout, the authorities easily achieved the desired results. The first serious error in this design occurred in the 2017 municipal elections, but the triumphant victory of Sergei Sobyanin in the mayoral election of Moscow a year later seemed to return the system to working conditions.

On September 8, there was no significant increase in turnout from 2014, at 21.04%, to 21.77% in 2019. However, the results were radically different. Now almost 40% of the seats will be taken up by people that City Hall did not plan to see enter the City Duma.

This means that dependent voters ultimately did not turn out to vote. Or perhaps they did vote under pressure, but did not vote as planned by election administrators.

The “Smart Vote” effect

As a result of the political mobilization of protest voters and the demobilization of conformists, the new Moscow City Duma ended up looking completely different from the picture expected to be seen by the Moscow City Hall. Candidates supported by Alexei Navalny’s Smart Vote initiative won in about two dozen constituencies. However, it is difficult to separate this from other factors that led to the victory of specific candidates and to evaluate the Smart Vote effect in quantitative terms. Different experts using different methods often seriously differ in their assessments, and often, these assessments correlate with experts’ own political preferences, as demonstrated in other analyses.

Indeed, to attribute everything to Smart Vote is to negate the work of the candidates themselves, and to consider voters to be exclusively obedient zombies following their leader. The case of Alexander Solovyov, who won in the third district, who didn’t even provide a photo to the electoral commission, seems to corroborate this readiness to blindly vote for any candidate backed by Navalny. Alexander Solovyov was a spoiler candidate against Alexander Solovyov, a member of oppositionist Dmitry Gudkov’s team later removed from the election. His “double” did not even conduct a campaign – evidently, he did not expect to be elected.

However, there is an opposite example in the figure of Roman Yuneman, who beat the Smart Vote candidate and is now trying to challenge the victory of establishment candidate Margarita Rusetskaya, who overtook the opposition by only 69 votes. Interestingly, her landslide victory in online votes – much higher than what she received in offline polling stations – ended up deciding the race.

If Yuneman had been the Smart Vote candidate, he certainly would have won. But Navalny’s team made a mistake, as was immediately pointed out by many experts and even residents of the district. This, incidentally, means that if any sociological research was actually carried out by this team at all, its quality leaves much to be desired. In fact, there is a feeling that Smart Vote candidates were selected based on other motives. So, in its own right, Smart Voting proved to be a rather effective, yet obviously manipulative technology.

As for quantitative assessments of the effectiveness of this call for the protest vote to be consolidated, the only somewhat reasonable assessment so far seems to be Boris Ovchinnikov’s analysis. He estimates the Smart Vote effect to account for 18-20% of votes – which is almost the same proportion of votes received by Sergei Boyko, the head of Navalny’s regional office, as candidate for mayor of Novosibirsk. Therefore, the approximate level of support for Navalny and his team in the largest cities of Russia should probably be evaluated at around these numbers, without even taking into account the effect of low turnout. In other parts of the country, this figure is certainly lower.

Summary

Election day put quite a few new faces previously known only to a narrow circle of activists on the map. Additionally, the results of September 8 likely killed the idea of online voting, having frightened a number of politicians and observers. The serious discrepancies in the voting results between “electronic” voters and offline ones made it certain that this system would lack any sense of credibility, as was indeed the case.

The 2011-2012 mass protests were a reaction to direct electoral fraud happening at polling stations. At that time, authorities took several steps to avoid the situation happening again. This does not mean that electoral fraud has stopped – the country still has about a dozen regions that experts call “electoral sultanates” (although the name is not entirely correct, because they include not only national republics, but also completely “Russian” regions such as Kuzbass). Nonetheless, the state of affairs concerning election days began to improve across the whole country. And electoral protests subsided for a while.

This happened thanks to tighter controls over the admission of candidates and over campaigns themselves: only specially selected people were able to register as candidates, and in order to prevent them from winning, media propaganda and voter coercion were deployed as tools. But now, this set-up no longer works.

Of course, the wave of protests that began over the summer has already subsided. But such waves will continue to be a chronic symptom of the systemic problems in Russian politics. The election commission system, the institutions of party representation, the lack of communication between citizens and the authorities –these are bound to only aggravate citizens’ discontent.

The next State Duma elections will take place in 2021, and promise to be very interesting. The Russian political machine is become a bumpy ride, so for the next two years, you had better fasten your seat belts.