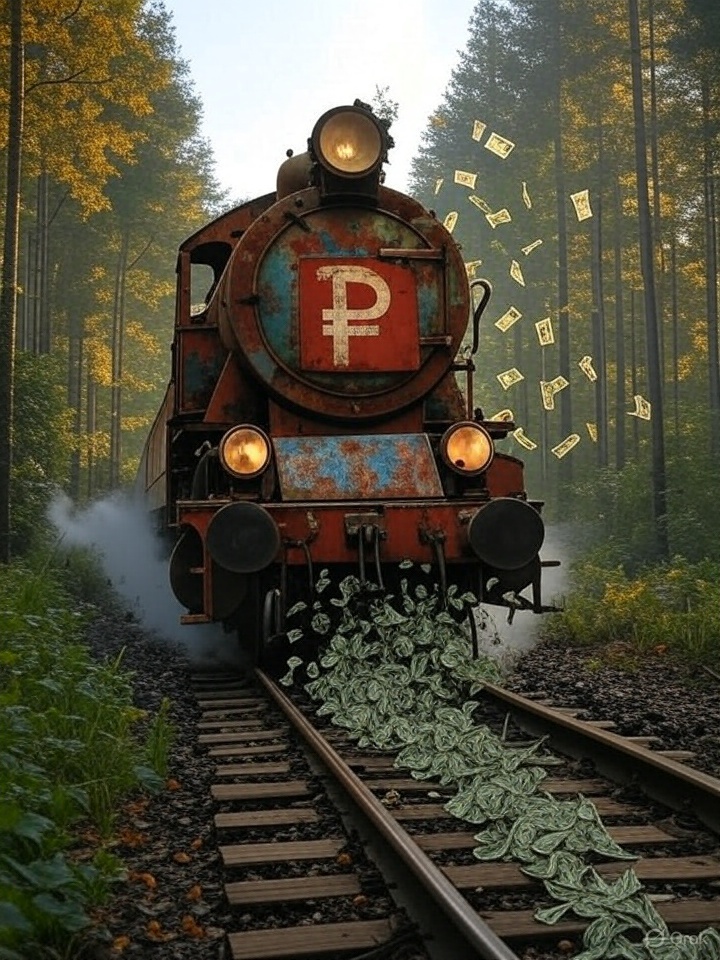

According to one of the scenarios of the presidential campaign, Vladimir Putin’s «Direct Line», which this year was combined with a press conference, was supposed to be the venue and the occasion for nominating the incumbent head of state. Although this plan was ultimately rejected, the campaigning element of the format was not entirely abandoned. Normally, Putin would single-handedly solve all the problems with great enthusiasm while communicating with the audience that is, in turn, coached and prepared well in advance. He would launch trains, deal with utility tariffs, give orders to bring gas or Internet to individual settlements. Such «gifts» were intended to promote social optimism among citizens and present the president as a benevolent and fair boss whom Russians can turn to in an emergency. The part of the Kremlin’s administration that is in charge of curating information flows, had promoted this very image before the «Direct Line with Putin» was scheduled to take place, presenting it as the last resort or hope for ordinary Russians. The last hope turned out to be in vain — the president was in no hurry to hand out presents. He gave his usual talks about Lenin’s role in the «creation» of modern Ukraine, the achievements of the Russian economy and the military successes at the front. For months now, Puin has been recycling these statements in nearly every public talk he gives. He could have added to these tirades some real solutions to social problems that the government and the presidential administration and the regional authorities used to prepare for Putin’s «Direct Line» well in advance. But citizens’ requests were drowned out by flattery-laden questions from journalists and war-related questions and speeches from «war correspondents.» Relatively few social inquiries were met with Putin’s response, which was not the most expected in the context of his election campaign: «There’s not much money in the budget, we’ll think about it. If revenues appear, then maybe the problem will be solved.»

«In general, we need to develop sports and all our programmes. By the way, in previous years we allocated about 1.5 billion, even more, I think 1 billion 700 [million roubles] from the federal budget for the development of regional and municipal sports. This year, there are not even 700 million roubles in the budget allocated for this purpose,» he told the youngsters, who asked the head of state to renovate their gym.

It is clear that the propaganda effect of the event, which the organisers presented as the last hope, is almost nonexistent. People were given the opportunity to outline their problems, but in response they heard that the government does not have the resources necessary to solve them. Moreover, Putin’s admissions of cuts in social spending contradicted his triumphant declarations about the outstanding success of the Russian economy. Not even the most economically savvy person in the audience would be puzzled by such a line. If the economy is doing so well, why are the authorities unwilling to spend money on social welfare? If there is no money to solve the above mentioned problems, perhaps the economy is not doing so great after all?

The presidential administration people have obviously tried to ensure that the «Direct Line with Vladimir Putin» does not unsettle or upset Russian society. They deliberately did not allow questions that would further divide the society. There was no mention of the wives of mobilised soldiers who are demanding the rotation of troops and the return of their loved ones to their families. The Kremlin clearly did not want to disappoint the angry women, but it also did not want to meet them halfway: any hint of rotation would would led to rumours of a new round of mobilisation. That would have sent a wave of anxiety in Russian society. Just in case, the presidential administration decided not to touch upon the LGBTQ+ issue, even though there were posters with rainbow ponies in the hall. In this sense, the presidential administration tried to keep the event running smoothly and rather calmly.

In running the «Direct Line with Vladimir Putin», the Kremlin was trying to reach two goals: on the one hand, to organise a noteworthy pre-election event and, on the other, to keep it as free as possible from sensitive issues. Neither goal was reached. The fact that the «Line» and the press-conference were heavily censored, with questions filtered in advance, made both boring and unexciting. Ordinary people, who pay little attention to politics, did not see the usual distribution of gifts when they heard about cuts in social budget items. Russians wanted to hear Putin clarify when the war against Ukraine would be over, but he said nothing about that. On the contrary, the president spent a lot of time talking about the war and, with obvious relish, about how well the newly mobilized soldiers were fighting. In the best case scenario for the Kremlin, this line will not affect society in any way, and will be neither noticed nor remembered. In the worst case, it will trigger new anxieties about social problems and the timing of the end of the war.

Roadshow

Putin’s roadshow continues with campaign-style trips to Russia’s regions. Last week he visited the Arkhangelsk region. This visit illustrates the peculiarities of Putin’s future pre-election regional tour.

Unlike the «Direct Line», the trip was not without gifts for the electorate. The president asked government officials in Arkhangelsk to provide new housing for residents of the old wooden houses «that were tilting so much that they were almost lying on their sides.» It is hard to say whether this order will be fullfilled. Putin regularly promises to «get people out of the slums», but nothing concrete comes of these promises. But at least the head of Russia has given a hint on how to solve one of the main problems of Arkhangelsk (and all of Russia). The president himself received many more gifts during his trip. Most likely, his election tour will be organised according to the canons of the «Rossiya» Exhibition and Forum which is supposed to show both the voters and the head of the country himself «the achievements of the Putin era». In many ways, political administrators and government officials are busy pleasing and entertaining an audience of one: they want to show Putin how he has supposedly changed the country for the better and make him feel proud of himself. In Severodvinsk, a major defence manufacturing centre near Arkhangelsk, Putin attended a flag-raising ceremony for new nuclear submarines. In Arkhangelsk itself, the president was shown around the city’s largest and most modern school.

Of course, it could be argued that flag-raisings on nuclear-powered missile carriers might stir patriotic feelings among the Russians and, in that sense, work for Putin’s election campaign. In reality, however, the event is unlikely to have a serious impact on public sentiment: propaganda has already convinced pro-government citizens that Russia is doing just fine as it is with its arsenal of missiles and their carriers. The visit to the school looks dubious from a PR and propaganda point of view. Putin’s visit to the construction site of an amenity long overdue, like a school or hospital, for which the local population has been waiting for a long time, could have had an effect. The president’s visit would be taken as a sign that the social facility will soon be in operation. For other Russians, it would be proof that Putin remembers the problematic construction sites and is willing to push local officials. A visit to a school that has been in operation for a long time has no such effect. It is only of interest to regional officials who can show off their facilities and count on the president’s favour if he likes the spectacle. Such visits do not affect or change the lives of the country’s citizens in any way. Campaign events should somehow point to the future, and raising the flag and visiting a school do little to generate a vision of the future.

In this sense, Putin’s regional tour departs from the electoral canon: it bears little resemblance to campaigning for the electorate. The figure of the voter moves from the centre to the periphery of the campaign, with the president becoming the main figure. Putin does not work for his electorate; on the contrary, regional and federal officials entertain him with shows and spectacles that interest him. The system has gone into a permanent mode of entertaining Putin in his spare time, and it does not abandon this mode even during the elections, when it is important, at least formally, to reach out to the citizens and try to please them. This was the case in 2012, for example, when Putin’s campaign included the so-called May decrees, which promised an increase in social welfare. This year, ignoring the president’s real work with his electorate is unlikely to have a global impact on the election results, which are mainly determined by the mobilisation of business, the mobilisation of budget employees and the opportunities for falsification offered by electronic voting that takes place over several days. If the socio-economic situation worsens, a campaign without clear promises and appeals to specific groups of voters may negatively affect the government’s ratings and the mood of the people. For them, all the good things will be confined to the past as they were shown in the exhibition about Putin’s past achievements, while the Kremlin has failed to give the citizens any hope for the present or the future during the «Direct Line» or during Putin’s roadshow.